Script for the Engines CD, Fall 2001

by John H. Lienhard

Mechanical Engineering Department

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-4006

jhl [at] uh.edu (jhl[at]uh[dot]edu)

Be sure to click on the links for additional pictures.

Information sources are given at the end of this text.

Track 1: This is only the data track. It is what opens your computer when the CD is placed in it. You should skip over it here, or in your CD player.

Track 2: Flying The Atlantic (4:30): (Continuing trip music theme) Let us make a long journey through Europe. Let us be tourists, seeing many things, some familiar and some not, but seeing each for the way in which it represents some leap of creative ingenuity.

Like any journey, we'll have to put restrictions on this one. The foundations of western culture, as they were formed in Egypt, Asia Minor, and Greece make too large a subject -- a topic for another day, perhaps. This trip will take us farther to the north.

The places and things we'll visit all exist today. You yourself may visit each of our way stations if you haven't already done so. But our aim is not to create a travelogue. Rather, I hope we'll all find new dimensions in old places as we move from place to place.

And, if we are to visit Europe, we must first get there. We shall, of course, fly across the Atlantic. Our first stop will be Shannon Airport in southwestern Ireland. Many people will be surprised to learn that the two first transatlantic crossings were made as long ago as 1919, and one of those two also landed in Ireland.

Commercial airplanes have been crossing the ocean since the late 1930's, about a decade after Lindbergh. But dozens of people had already flown the Atlantic before Lindbergh made his historic nonstop flight in 1927.

A view of luxury air travel, ca. 1927

We've somehow forgotten all those earlier flights. The first transatlantic flight, made in May 1919 from New York to Plymouth, England, was done in a six-man, four-engine, Navy flying boat, which stopped in the Azores and Lisbon on the way. Raymond Orteig of New York City immediately offered a $25,000 prize for the first nonstop airplane flight from New York to Paris. Just one month later, Alcock and Brown flew a two-engine airplane nonstop from St. John's, Newfoundland, to Clifden, Ireland.

In July 1919 a British dirigible flew from England to New Jersey and back. Then, in 1922, two Portuguese aviators, Cabral and Coutinho, flew a single-engine British seaplane from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. That's a longer flight than Lindbergh's but there's a catch. They didn't just stop over on the way; they actually changed airplanes on a small Atlantic island.

More flights from New York to England followed in 1924. And in 1924 a Zeppelin dirigible flew from Friedrichshaven to Lakehurst, New Jersey. Finally, 1927 saw seven transatlantic heavier-than-air flights, of which Lindbergh's was the third.

So what was so special about Lindbergh's flight? Well, it was the longest, nonstop, heavier-than-air, transatlantic flight and it was the first solo crossing. That's how he picked up the nickname, The Lone Eagle. And his flight finally fulfilled the difficult specific conditions of the Orteig prize, which had, by then, been waiting more than eight years.

If you've flown to Europe before we began this trip, you know how much longer it takes to get back than it takes to go. Prevailing west winds oppose you on the return. No one managed a solo heavier-than-air flight from East-to-West until 1932. Then a pilot named James Mollison got from Ireland to New Brunswick. It was 1936 before Beryl Markham finally flew from England to the Canadian mainland. (She told about that in a beautifully written book, West by Night.)

Hers was the last step that had to be taken before commercial transatlantic flights began in the late 1930's -- twenty years after the first transatlantic crossing and thirty-five years after the Wright brothers.

Still, Lindbergh's flight is what riveted public awareness; and it's worth mentioning his airplane. Lindbergh was a determined airmail pilot who finally found a like-minded designer at the tiny Ryan Airplane Company. Ryan specially built the Spirit of St. Louis for Lindbergh in just two month's time. They called him Lucky Lindy. But his luck was the making of many people. It was finding the right engineer at the right time. It was the luck of having a great parade of risk-taking and courage before him. Indeed, the word luck may not really apply to the courageous focused intensity that Lindbergh brought to the one flight we all remember as first.

Track 3: Ceide Peat Bogs (2:46): (Continuing trip music theme) And so you and I reach Shannon Airport. After a day in Limmerick, recovering from jet lag, we rent a car and drive to the far northwestern corner of Ireland. Our first stop will be a remarkable and ancient ecological mistake.

It takes about three hours to reach the Ceide Fields. This is a huge peat bog stretching along a promontory that looks out over the Atlantic: These bogs are a phenomenon created by human occupancy. Five thousand years ago, stone-age farmers cleared trees from the land. Before they did, the trees held most of the rainfall. Now rain could penetrate the ground. Worse yet, rainfall increased during those years. Mosses grew, and the sodden land turned to peat.

Those farmers had unwittingly attacked the environment. Now the environment attacked them. Bogs took over -- here, and many other places in Ireland as well. Bogs wrecked the land and drove the farmers out. Peat filled in over the abandoned villages.

Now we cut away the peat. We meet the people who once lived here. These late Paleolithic farmers had crossed the Irish Sea from England. They brought their dogs and cattle with them. They used the cattle both for food and as draft animals. The dogs? Who knows! Maybe they were just friends.

The village scatters along the cliff and low stone fences divide it. These people owned their land and built individual houses. The houses were a mixture of wood and stone. There's no evidence of defense. Each house is isolated and unprotected. It had to have been a harmonious life in a cooperative community.

Peat preserves dead bodies, as we shall see when we reach Denmark. But we find no bodies here -- at least no human ones. We do find a stray pig, thousands of years old, but no humans. We also find elaborate tombs with human ashes in them. These people clearly had religious traditions for disposing of their dead. They had no written language yet, but they did have art. We find fragments of decorated pottery.

So, for roughly two hundred years, this hamlet flourished on the edge of a cliff above the harsh North Atlantic. Three hundred or so people cleared trees, tilled their gardens, and watched the seasons turn. Before the Pharaohs, this gentle people lived a gentle life. Then the peat sent them away and created the lovely, stark, green-brown gorse that shifts its colors under the slate-gray skies of Ireland today.

Of course, they drove themselves away because they couldn't know the consequences of their modest assault on the environment. And, in that, our kinship with these old Irishmen might be stronger than we like to think.

Track 4: Tabby And Cobb (3:42): (Continuing trip music theme) From the Ceide Fields, we drive due east about fifty miles to the town of Sligo. It's a good place to pause for a day. This was the home of poet William Butler Yeats. Our interest here is not directly in Yeats, but rather in a train of thought triggered by one line of his remarkable poem Inisfree. Yeats sets us to thinking about a huge part of domestic technology.

Yeats dreamt of building a retreat on a tiny island in the small lake, Inisfree. He wrote, "I would a cabin of mud and wattles make." For me, that brings back another visit to Europe. Years ago, I taught for a season in Southwest England. We lived in the old Anglo-Saxon town of Crediton -- in a thatch and cob cottage there.

That cottage had stood for five hundred years. Thatch is the thick woven straw that makes the roof. The walls are a mixture of clay and straw called cob, or sometimes tabby. The material varies, as well as the name. Cob, or tabby, is a poor man's masonry. To make it, you mix a structural material -- like straw, corn stubble, or oyster shells -- with clay or earth. It makes a solid building material. In one form, we daub mud onto it. Wattles, by the way, are twigs woven together.

Cob was probably invented by the Phoenicians. The Carthaginians learned it from them. The Romans learned to make cob from the Carthaginians. Later, the Romans invented concrete. After that, we find walls of concrete cob that still stand today. Cob went from Rome to Spain, and into Europe and England.

The written record of tabby and cob is confusing because it has to be reinvented in every land. Mud, clay, and all the filler materials occur in such variety that the stuff defies identification. In the early 1500s, building on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, was expanding rapidly. Tabby was the best low-cost building material. Records say that tabby workers who came from Spain didn't know what they were doing. In fact, it simply took a while to invent techniques for using local materials.

So I go back to that wet winter in Devon, living in a cob house. One night at supper, we heard a chilling PLOP. We turned and saw a huge scar on the wall. A square foot of clay had fallen out and splashed over the floor. Cob, it seems, must be patched regularly. And so it had been for five hundred years before we came.

Mud and filler composites are among the oldest and most widely used materials on earth. We live in boxes of concrete and glass -- wood, brick, and steel. We forget the potential, even today, of odd mixtures of materials. We forget mud and straw.

Mud and filler composites are among the oldest and most widely used materials on earth. We live in boxes of concrete and glass -- wood, brick, and steel. We forget the potential, even today, of odd mixtures of materials. We forget mud and straw.

The poet, Yeats, dreamt of going back to Inisfree -- to that tiny wild island in a lake near Sligo, in Ireland. He dreamt of creating a simple place to be -- of fashioning it from mud and wattles. I doubt he ever really tried the trick. Cob may be a poor man's masonry, but it's not a poor craftsman's enterprise.

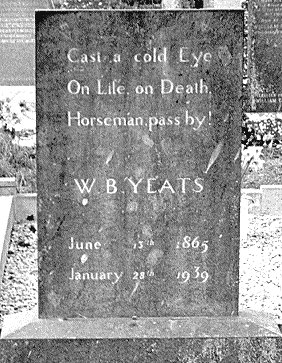

Yeats is buried near Inisfree -- near the place where he dreamt about shaping clay. When he passed back into earth, he left these words, which we read on his head stone: "Cast a cold Eye, On Life on Death, Horseman pass by." The old walls of mud & wattles -- of tabby and cob -- are the earth -- they are the spit and clay that've formed our civilization. (Theme Music outro)

THE LAKE ISLE OF INISFREE

I will arise and go now, and go to Inisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honeybee,

and live alone in the bee-loud glade.And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight's all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet's wings.I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart's core.

William Butler Yeats

Track 5: An Old Company Town (4:05): (Continuing trip music theme) After a night in Sligo we set out again. We cross into Northern Ireland at Straban, and drive to Larne in the Northeast corner of Ireland. There we take the car ferry across the North Channel.

We arrive in Stranraer in Scotland and, from there, head eastward across the border into England. We find lodgings in the town of Carlisle on the western edge of Hadrian's Wall. The next day, we walk sections of the wall. And we think about Hadrian who was both an Emperor and an architect. When we get to Rome we'll visit the great Pantheon, which also owes much to him.

But, now we visit sections of the wall Hadrian built to keep the Celts out of England. It was once sixteen feet high, and it extended for seventy-three miles just below the Scottish border. What remains today is only about three feet high, and large pieces are missing. But we'll better understand the accomplishment that it represents when we meet Hadrian again, in Rome.

After a second night in Carlisle, we continue south to the town of Merthyr Tydfil in southern Wales. This is young town by local standards. It's a creature of the Industrial Revolution, a town that has been many things over its 250 year life.

You and I look at the wake of the Industrial Revolution with justifiable revulsion. We think of mill workers enslaved by heartless companies in squalid factories. We remember Charles Dickens's pictures of England in the 1840s -- images of a life barely better than the slavery still going on in America.

None of that here! Merthyr Tydfil has an internationally known men's chorus, and it was also the town where the TV series Dr. Who was produced. A bucolic gem of a hotel here was once a lodge owned by the Morgan family. For centuries, the Morgans owned everything in this region. Historian Bruce Thomas tells how an enterprising cleric named Thomas Lewis negotiated a lease for two thousand acres of Morgan's hunting lands in 1759. He knew there was coal here, and he wanted to set up iron forges.

That same year young James Watt went to the University of Glasgow as an instrument maker. Modern steam engines would soon be in the picture. Industrialization would create the new town of Merthyr Tydfil here. In a few years it would become a showplace powered (for the moment) by a huge iron water wheel, fifty feet in diameter.

Local peasants left their medieval lives in the isolated outback. They came to work the forges. They built small stone row houses. Their standard of living advanced by a light year. Now they had minimal medical care and schooling. They bathed daily. (They had to in their filthy work, but that set them far apart from the rest of England.) They whitewashed their new houses and outhouses. Bookstores appeared in the new town. People read.

But the forges came and generated filth. Soot covered everything. Visitors who'd been impressed were now appalled. Thomas Carlyle called Merthyr "a vision of Hell [that'll] never leave me."

Towns like this were raising the standard of living and raising expectations. The first dwellers in Merthyr Tydfil had left an unimaginably primitive life. The second generation was raised in a world transformed by the fruits of these new industries.

In 1831 the citizens finally rose up to demand some semblance of public service. They wanted their streets cleaned and lit, they wanted public bathhouses, they wanted city government. Blood soon flowed in the streets; then cholera followed. Finally, in 1856, the Bessemer process took steel making away from this now-miserable town. Changing the industry is what finally undid the slum. The workers left, and Merthyr Tydfil grew bucolic again.

Now the town means TV, choral music, and sail boating -- amenities of the good life it helped to create. In the end, Merthyr Tydfil really has done what it set out to do, over two centuries ago. (Theme Music outro)

Track 6: The Duchess And Greenwich (3:02): (Continuing trip music theme) On to London where we might spend a day, we might spend a month. But I do have one place I want to take you. It's Greenwich -- on the Thames, just to the west -- home of the wonderful sixteenth-century Royal Observatory and the place where time received its name.

While we make our way through crowded London you might be interested in a very odd sidebar on the creation of that observatory. This story begins when King Charles II took yet another mistress in 1670. She was a dark-haired beauty from Brittany in France. She bore a son two years later, and the King made her the Duchess of Portsmouth. The Duchess was the King's clear favorite. Some wondered if she might not be a French spy in the English court.

By now a scientific question was gathering importance. This was the age of navigation. European ships were ranging the oceans. It was easy enough for navigators to fix their latitude. But no one knew how to find their ship's longitude. That was the uncertainty that almost killed Columbus, 180 years earlier.

The King had recently created the Royal Society to advance science. Now the Society urged him to build an observatory. We needed better astronomical data to solve the longitude problem. The proposal was foundering in red tape. Then the Duchess produced a friend from Brittany. He was an amateur astronomer named St Pierre. Once in the English Court, he claimed he could calculate longitudes.

In December 1674, the King set up a Royal Commission to study St Pierre's method. It included Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke. Those were heavy hitters. But, for astronomical advice, they turned to a young man named John Flamsteed.

Flamsteed saw that St Pierre's method was inherently inaccurate. Worse yet, he'd taken it from two other astronomers, long dead. And when Flamsteed questioned St Pierre, he found the fellow didn't even understand the method he was proposing. Flamsteed reported to the King that we'd have to get longitudes by another method entirely. Then we'd only do it when we had far better data on locations of stars and planets.

Flamsteed's answer to St Pierre made it crystal clear that England urgently needed the observatory. King Charles reacted. That very day he signed the warrant to build the Greenwich Observatory. He set up the world benchmarks for longitude and time.

The Duchess's friend St Pierre went back to France and we don't hear from him again. Yet he and the King's mistress had precipitated one of the important scientific projects of all time. Ten years later, the King elevated another mistress to the aristocracy. He made her -- not the Duchess -- but the Countess of Greenwich.

So the King and his court swirled about and played their roles. But in the midst of it all was quiet John Flamsteed. And it was he who really redirected history in this place we now visit. (Theme Music outro)

Track 7: The Sensory Paris (3:24): (Continuing trip music theme) Let us next take ourselves to France. It's just a short drive down to the village of New Haven, just south of Brighton. That's where we catch the car Ferry to Dieppe.

The English Channel is cold and rainy this day -- heaving gray water under gray skies. The huge ferryboat is an English/French world. Few other countries are represented. As we leave New Haven, everyone speaks English. Near Dieppe, French accents intensify. Finally, people stop understanding my English and I begin recalling bits of schoolboy French. We debark and drive off toward Rouen.

Here in Normandy, the iron armies of 1944 passed over like angels of death -- pulverizing the ancient towns. We walk by the tower where Joan of Arc was interrogated during another awful war, almost six centuries ago. We pass terrible WW-II bomb scars on the Hall of Justice, along the way to Rouen Cathedral.

The cathedral is stunning. Its immense columns and arches distort and expand space. These stones surely violate the law of gravity! The building assails the senses. We've entered a kind of fourth dimension, and I struggle to resolve it with reality.

But we see only fragments of the fifteenth-century stained glass. Only a pane here and half a window there has survived the bombings. Heads are blown off statues. After fifty years, the restoration still has far to go. A new window shows women in a grain field, one with a wide straw hat. They could as well be Vietnamese as medieval. They could be bystanders from any war.

After half an hour, the geometrical unreality, the poignant beauty, and the sense of violation by war grow too strong. I go back out into the quiet rain to clear my mind. In a shop across the street I pay 100 francs for a frayed science book, published in 1745 -- a set of conversations on the senses. How do sight, touch, hearing, taste and smell work? What do they really tell us about reality? The book tells of Newton's new theory of light spectra and it includes an early picture of the inner ear. But none of this explains how vision and gravity failed me inside Rouen Cathedral.

And so we continue on to Paris and the sensate assault continues over the next few days. It hits me again in the Musée d'Orsay, amidst the Pre-Raphaelites and Art Nouveau. Suddenly the assault on the senses was too explicit. I drop my guard and feel too much. I have to flee to McDonald's on Rue St Germain for a cup of coffee. I need some blandness during a meal too rich for the taste buds.

Now, at last, we eat one last perfect pâté -- take one last walk among buildings whose physical beauty and elegance mock the mere shops and cafes they now house. We've been through the museums here: rank on rank of Van Gogh, Monet, Rodin. In the Louvre, the Mona Lisa, Venus deMilo, and Winged Victory -- they all went by like pictures in Art Appreciation 101.

It's time to go on to some new and different adventure. We'll have to sort all this out and rebuild it in our minds -- make sense of it in retrospect -- after we get back to America. (Theme Music outro)

Track 8: The Book Of Chartres (3:09): (Continuing trip music theme) We collect our wits as we drive away from Paris to the southwest to find a very particular oasis of calm. As we approach the small town of Chartres, the first thing we see is the spire of Chartres Cathedral.

This is the first and finest High-Gothic church. It's built upon a site where the Romans had once built. Then a series of churches, each grander than the last, rose upon this spot. When fire damaged the cathedral that stood here in 1194, it was a sign to the people of Chartres that their protector, the Virgin Mary, wanted a still grander church on this spot.

Whether or not that's what Mary really wanted, it's what she got. Technologists came from all over France. They threw heart and skill into creating such size, intricacy, and lasting beauty as to set the standard for Gothic architecture ever since.

Much of what I see at Chartres I'm prepared to see. Then the unexpected: we meet Malcom Miller, who came here from England 38 years ago and fell under the spell of 21,000 square feet of stained glass, still brilliant after eight hundred years. It's the finest there is, and he knows it better than anyone. We sign up for his tour.

Chartres, he explains, was the Oxford/Princeton of the medieval world -- a great learning center and library. And where is the library? Why, all around us! For an hour we read some of the ten thousand images of saints, sinners, and common folk who tell their stories in stone and glass from every wall, window, and doorway.

Example: The story of the Good Samaritan, told from bottom left to top right of a window in the nave. The pictures, evocative and wordless, draw us in. First picture: a group of shoemakers pools money to pay for the window. Then the story: a man leaves Jerusalem and is beset by thieves who mug and strip him. A priest and a Levite pass him by. Finally a despised outcast -- a Samaritan -- stops to give aid. And you know the rest.

The parable ends with the Samaritan promising the innkeeper to come back and settle accounts. But we've read only half the window! There follow layers of interpretation -- the parallel between the robbed traveler and outcast Adam. The Samaritan's promise to return becomes the promised second coming. It's subtle, and a huge cast of accurate medieval figures acts it all out. (My wife counts fifty-two humans, one donkey, and a snake.)

These are no Saturday afternoon cartoons for uneducated peasants. This is serious scholarship for a smart public who, in a world with few books, doesn't read. Although the cathedral begins by assailing the senses with its vast and blurred symphony of color and space, shape and light, we're gradually drawn into its seemingly infinite library of artistic and architectural detail.

And I think about the practical, unlettered people who made this place -- who shaped a living book that reaches out across eight centuries and speaks to us with eerie eloquence. (Theme Music outro)

Track 9: A Dark Age Ends In Poitiers (3:00): (Continuing trip music theme) The next day we continue south to the city of Poitiers. This is where Europe found its way out of the ancient forests and began a course that would eventually create a northern European civilization.

One particular building offers a glimpse into how that worked. It's the Poitiers Baptistery, built in the seventh century. This little stone church is only a dim memory of Roman architecture. Its arches, pillars, and lintels are only decorations built into the walls. Their original structural purpose has been lost.

Now you and I were raised on the old notion that a Dark Age lay between the Roman Empire and a modern Europe. Much of medieval Europe was far from dark. Between the tenth and the fourteenth centuries, civilization was reborn. But earlier -- in the near wake of Rome -- things really were pretty bad.

As the Roman empire closed down, her northern reaches faded back into the forests. An old Anglo-Saxon poet looks at remains of the old Roman glory. He looks at husks of once great buildings and says,

A wise man may grasp how ghastly it shall be

When all this world's wealth standeth waste

Even as now, in many places over the earth,

Walls stand wind beaten,

Heavy with hoar frost; ruined habitations ...

The maker of men has so marred this dwelling

That human laughter is not heard about it

And idle stand these old giant works.

Northern Europe had barely subsisted for quite a while. Marauding Vikings and nomads swept across it. Primitive peasants looked at those great ruins like so many dinosaur bones.

Many of the great Roman aqueducts, ampitheatres, and arches still stand. But they made little sense to people for whom life was a brief exercise in survival. Rome had built all that on the backs of slaves. One thing we can give the Northern European peasants is that they were not slave-keepers. That meant they would need a power source before they'd ever rise above mere subsistence.

Eighth-century France finally began giving us new power sources. First, farmers learned to use horses. Then they gained full control of waterpower. After that, they too started building a civilization -- one that would soon surpass Rome.

But now we stand in Poitiers, looking at this crude building -- begun in the fifth century and remodeled in the seventh. It is a valiant attempt to start a new life with grace and beauty in it. Like the old Roman structures, it was meant for posterity. And it does still stand today.

But they hadn't got the hang of it -- not yet. Five hundred years later they'd build Gothic cathedrals and more. So we gaze at this pretentious little church -- this determined attempt to leave the forest. And it speaks a bold, roughhewn grandeur of the inventive spirit. In an odd way, it becomes just as moving as Rouen or Chartres Cathedral. (Theme Music outro)

Track 10: El Cid And Aristotle In Toledo (3:18): (Continuing trip music theme) Now let's do some serious driving. We'll spend some time on a six hundred mile trip, across the Pyrenees to central Spain. We're headed for the city of Toledo.

Of course it'd be cruel and unusual punishment not to spend a few days in Madrid -- to visit the Prado Museum, to wander the open bookstalls, to see the fine architecture of downtown Madrid. But I chafe to reach Toledo. For that's where the seeds of modern science first sprouted in Europe. Perhaps you remember Charlton Heston playing the Spanish hero El Cid and freeing Toledo from Moslem rule in AD 1085.

Never mind that the real El Cid was in fact a murdering, looting barbarian. Never mind that he wasn't even around when Toledo fell. Actually, Toledo's Moslem ruler opened the gates to the Christians so he could escape from enemies inside the city.

Still, this was a great moment in Western intellectual history. When they got to the library, Christian scholars learned how far they'd fallen behind the Moslems. For centuries Jewish and Arab scholars had preserved the ancient Greek books here. Plato and Aristotle were only distorted echoes in the Christian world. Now Europeans saw their legacy first hand and were stunned by its brilliance.

The scholars of Toledo led academic tourists from the North through their trove of literature. Those visitors felt like primitive savages among the mountains of newly discovered books. The works of Aristotle presented them with a kit of logical tools that opened a stunning array of capabilities. They rediscovered the syllogism -- that miraculous means for using two facts to generate a third. For example:

Skin gets wet with perspiration.

Moisture escapes from things through holes.

Therefore, skin must have small holes in it.

We've suddenly generated a third fact, seemingly out of thin air. The French scholar Pierre Abelard seized on the new logic. He turned Aristotelian dialectic loose on Holy Scripture. "By doubting we come to inquiry," he said, and "by inquiring we perceive the truth." And that says commentator James Burke, was revolution. Abelard wrote four rules for inquiry:

Use systematic doubt and question everything.

Learn the difference between rational proof and persuasion.

Be precise in use of words, and

Expect precision from others.

Watch for error, even in Holy Scripture, he added. It's taken five centuries for science to fully embrace this old logic in its new wrapper. For the moment, theologians tried to ride the shock waves Abelard had unleashed.

Medieval lawyers were first to arm themselves with these new tools. By the mid-thirteenth century, the Church finally acknowledged Aristotle. When they did, Thomas Aquinas moved in and built a theology based on Aristotelian logic.

Out of that came a new theological statement: No longer "understanding can come only through belief," but rather, "belief can come only through understanding." And there, of course, was modern science in its embryonic state. And all that happened right here. (Theme Music outro)

Track 11: The Leaning Tower Of Pisa (3:08): (Continuing trip music theme) Now, another long drive. We follow the coast of the Mediterranean through Vallencia, Barcelona, Marseilles, Nice, and Genova. We come at last to Pisa.

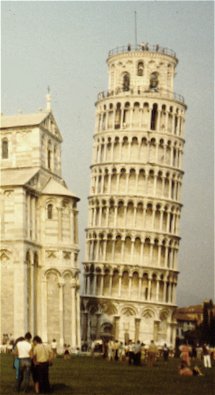

The famous Leaning Tower turns out to be a kind of architectural time machine. As much as does meet the eye here, there is far more that does not. Medieval architects outreached themselves. The Gothic buildings that stand are a remarkable legacy but we see few of their failures. One of those failures, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, is a marvel to see. The Leaning Tower, like many other old Tuscan towers, sits on soft soil. It's only one of many that've gone askew in various ways. But none is more dramatic. Its height, after eight hundred years of tilting and sinking into the soil, is about 184 feet.

The famous Leaning Tower turns out to be a kind of architectural time machine. As much as does meet the eye here, there is far more that does not. Medieval architects outreached themselves. The Gothic buildings that stand are a remarkable legacy but we see few of their failures. One of those failures, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, is a marvel to see. The Leaning Tower, like many other old Tuscan towers, sits on soft soil. It's only one of many that've gone askew in various ways. But none is more dramatic. Its height, after eight hundred years of tilting and sinking into the soil, is about 184 feet.

I always thought of the Tower as a Renaissance building, but it's older than that. Its construction began way back in 1173. When builders finished the first third, they found it'd tipped two tenths of a degree to the northwest. So they put it on hold for a century. By then the tilt had extended to seven tenths of a degree.

Yet the city fathers resumed construction anyway. Masons squared off the top of the tilted stump and built upward. The Tower tilted again, this time to the north. They stopped again. For another century the Tower sank and tilted -- to the north, to the east, and finally to the south.

With the Tower now leaning almost two degrees to the south, work went ahead once more in 1373. Masons squared off the top a second time and finished the Tower. Now the top was straight, but the lower portion had a gentle but permanent corkscrew shape.

The Tower has continued tilting at an average rate of twenty-one seconds each year. Now it moves only seven seconds per year, but that's cold comfort when it leans almost five and a half degrees off vertical -- nearly a ten percent tilt.

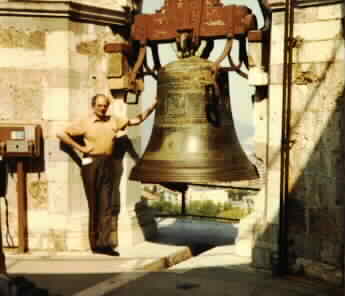

And so it stands, majestic and eerie -- defying the rules of fall that Galileo learned upon its summit. Years ago they still let people walk to the top. The stair coils about the outside. You had to cringe against the wall each time you negotiated the south face and hung over empty space. You reached the top, short of wind, and gazed out over the ancient intellectual center of Pisa.

But there's one more tight circular staircase. You took a deep breath and mounted it. Now you could gaze down, even on the bells. Nothing more separating you from the blue Tuscan sky.

We have to wonder what medieval magic keeps the Tower from abruptly finishing its fall. Civil engineers have learned what its medieval builders didn't know about foundations, but they haven't learned how to end the Tower's movement. With an animal obstinacy, it curbs experiments. It responds to each measure by tilting faster, and it teases our minds with its crazy, slow motion, corkscrew fall. (Theme Music outro)

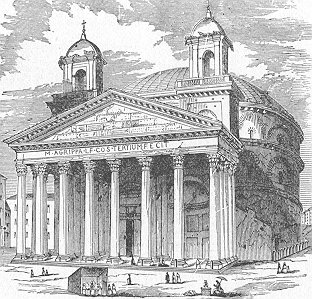

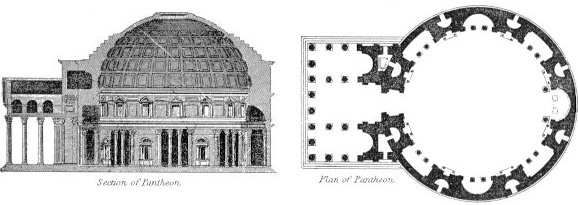

Track 12: The Pantheon (3:14): (Continuing trip music theme) The next leg of our trip is only a little over two hundred miles down the west Italian coast, to Rome. And Rome can certainly occupy us for days. But I have one particular site in mind.

We visited Hadrian's Wall in Track Four. But Hadrian's great contribution to architecture is the Pantheon, here in Rome. For it was here that he attacked a fundamental problem of architecture -- that of creating interior space. Igloos and wigwams offer clever means for gaining unobstructed indoor space. Houses offer more space, but that space has to be broken up into rooms. The large unobstructed space offered by Indian and Neolithic long houses was awkwardly long and narrow.

We visited Hadrian's Wall in Track Four. But Hadrian's great contribution to architecture is the Pantheon, here in Rome. For it was here that he attacked a fundamental problem of architecture -- that of creating interior space. Igloos and wigwams offer clever means for gaining unobstructed indoor space. Houses offer more space, but that space has to be broken up into rooms. The large unobstructed space offered by Indian and Neolithic long houses was awkwardly long and narrow.

How then to create indoor spaces, as wide as they are deep, spaces for large gatherings: temples, churches, closed arenas, assembly halls? The Egyptians didn't manage it, nor did the Greeks, for all their fine architecture.

In 25 BC, Agrippa dedicated the Pantheon to all the gods. The word Pantheon means of all gods. But that didn't incur proper divine protection for the wooden building. Destructive fires razed it in 80 AD and again in 110 AD.

Hadrian was emperor of Rome during the second fire. He was an extremely effective leader, as well as a fine architect. Besides Hadrian's Wall, it was under him, and with his involvement as an architect, that a new Pantheon was erected in 126 AD. This one was destined to become an architectural landmark for all time.

The Pantheon is a large pillbox of a building with a square classical front on one side. You enter that front, and it leads you into the largest domed space the world would see until 1800 years later. The central chamber is 142 feet in diameter, and its top rides 142 feet above the floor.

This is no Gothic arch of stacked stone. It's a far more modern construction. The dome is cast concrete, decorated with an elaborate waffle pattern on the inside. At the top is another surprise. The center is a 27-foot hole - an oculus, or eye, which carries light into that great inner space.

The cast concrete dome seems to've originated with Hadrian. Previous attempts to build with concrete had warned the Romans to make serious changes in the way they used concrete. So the Pantheon sits on a foundation ring fifteen feet deep and twenty-four feet wide. It's also buttressed by concentric outer support rings. The shell of the huge dome not only tapers from a thickness of twenty-two feet down to five feet.

Roman engineers also graded the density of the concrete so the material is lighter near the top. During the seventh century, in now-Christianized Rome, this temple to all gods became the Rotunda of Santa Maria. In that role it may command less attention than Notre Dame or St. Peter's. Yet, if you ask anyone who's taken time to see that great sky lit hemispherical space, they'll tell of being caught off-guard by its surpassing ancient glory.

But for the moment, we visit sections of a far less spectacular ruin. Hadrian's wall was once about sixteen feet high and it extended for seventy-three miles just below the Scottish border. It was a remarkable feat. What remains is only about three feet in height with large pieces missing. But let us keep Hadrian in mind until we reach Rome. (Theme Music outro)

Track 13: Castel Del Monte (3:32): (Continuing trip music theme) Let us take our time today. We drive from Rome to Naples, and then turn inland. We'll cross the Apennine Mountains and emerge above the Adriatic Sea. Our next stop is the town of Andria.

Here we want to visit a remarkable piece of ancient architecture -- a strange side road in the history of building. It is the Castel Del Monte.

This building reminds me of designing an apparatus to be used in semiconductor research while I was in the army. I felt the need of intellectual elbowroom so I contrived to build every conic section into the apparatus. Around the functional parts I shaped an array of lovely, purposeless, soul-satisfying curves -- parabolas, circles hyperbolas and ellipses.

The Castel Del Monte was designed in a similar way by a thirteenth-century emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick II. Frederick was a scholar and an architect. He knew Arabic as well as Latin, and he was influenced by all he'd seen on a crusade into the Arabic world. He founded the University of Naples. He was also a friend to the great mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, who introduced the Arabic representations for zero and ten into European calculation.

Frederick's architecture is marked by strong planar surfaces with circular towers and half-towers. It's all very geometric -- even willful. In the words of one architectural historian, it makes no concession to the land around it. And the imprint of abstract Islamic ornamentation runs through Frederick's work.

He built the Castel Del Monte in the 1240s. In this land where snow is rare, it reminds us of the fractal shape of snowflakes. It's a perfect octagon, 123 feet across, with an octagonal center court. Octagonal towers on each corner carry the octagonal theme downward in scale. Its floor plan reflects octagonal Islamic tile work. It makes me think of my own play with conic sections. It's an eye-catching exercise in geometry that outruns any purpose.

So why did Frederick build it? His castles all over Sicily and southern Italy were certainly meant to express imperial power. But in this building we see something more. It's a dark and closed place inside, with a form so coolly mathematical as to be beautiful. A contemporary looked at it and wrote Stupor mundi et immutator mirabilis. That was more an astonished outcry than a sentence. It meant something like, Amazed world -- wondrous novelty!

Frederick's son Manfred died in battle in 1266, and Frederick's three grandsons were condemned to life imprisonment in the Castel del Monte. One escaped after thirty years, only to disappear into Egypt. And that dreary footnote is the only role in history I've been able to find for this medieval exercise in geometry.

This not-quite-beautiful castle chokes on self-indulgence. When I went back to Fort Monmouth in the 1960s, and found my apparatus still in use, it was an enormous relief. My own self-indulgence hadn't been quite been enough to have made the design useless. Any good design must have the designer's personality written upon it. But it should be etched lightly. It should be there, but only hovering -- only an aura. (Theme Music outro)

Track 14: A War Requiem In Bosnia (3:21): (Continuing trip music theme) It's only another thirty miles south to Bari, on the Adriatic coast. We'll spend the night there and, the next day, we'll take the ferry across to Dubrovnik.

Track 14: A War Requiem In Bosnia (3:21): (Continuing trip music theme) It's only another thirty miles south to Bari, on the Adriatic coast. We'll spend the night there and, the next day, we'll take the ferry across to Dubrovnik.

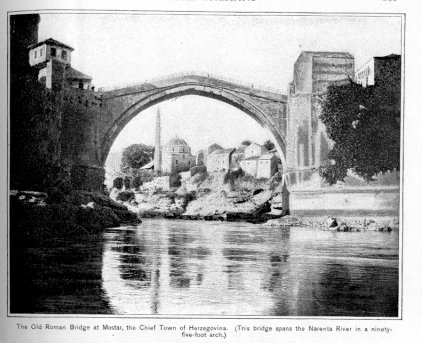

There's so much to see in Jugoslavia, but these are hard times. We'll head north to skirt around Kosovo. About sixty miles up and inland is the historic city of Mostar in the foothills of the mountains. Here we find so many remnants of the recent war and my mind drifts off to a concert I went to in Houston, a few years back.

How strangely things came together that Sunday afternoon! Robert Shaw had directed Benjamin Britten's War Requiem -- a setting of a poem by Wilford Owen. Owen was an English soldier killed in the last days of WW-I.

In 1948 I sang under a Shaw protégé. Shaw was, by then, the young wunderkind who was transforming American choral singing. I was studying calculus, mechanics -- and singing -- surrounded by returning WW-II veterans. I'd survived the war by being just a little too young to go. The students around me -- some damaged, some not, had survived by being luckier than the ones who died.

I went on into engineering and teaching. All the time I sang everywhere I could. In 1974 I was in Jugoslavia singing with the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral and working in the International Center for Heat and Mass Transfer. That August I drove down through Bosnia, and through Mostar, to a conference in Dubrovnik.

The car carried my wife and me, our two boys, and the conference proceedings. We stopped near the famous Mostar Bridge for our sandwiches and juice. Bees hummed in the summer air, and the graceful bridge reflected in the river water.

The Bosnians were nice to us. A couple took us into their house that night. Their daughters slept on the couch. Other Jugoslavs were nice to us, too. But they told jokes about the Bosnians. They told the same jokes I'd once told about the Polish.

Now we look at the ruins of Mostar Bridge. Croatian guns pounded it into rubble. The terribly slow efforts at historic restoration are underway, and I know I'll never tell Polish jokes again.

In any case, Robert Shaw was still at it that Sunday afternoon, a half-century after my student days. And I think about those ex-GIs. Art Winship finished his degree in a wheelchair. John Wagner had survived the terrible 1945 German counteroffensive. That whole part of my life had played to the background of Shaw's musical methods while students around me confided the horrors that Owen wrote about. And the same sort of senseless death had taken place here.

I think of Wilford Owen dreaming up the ghost of a soldier he'd killed. The ghost speaks:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now ...

It was another world when I sang, and studied coal gasification, here. I listened to Bosnian jokes and sat by Mostar's lovely bridge. Now, I simply feel the need to hurry on. (Theme Music outro)

Track 15: Byzantium (3:13): (Continuing trip music theme) We continue northeast through Sarejevo, then west to Niš, and southeast into Bulgaria. There we stop for the night in the capital of Bulgaria -- in Sofia. The next day, the road crosses into Turkey and we immediately pass the lovely mosque at Edirne. We continue through flat dry country, arriving at last at the final outpost of Europe. We reach Istanbul.

Some years ago, I played a curious game to do an Engines program. I used my computer to generate a random date and then did a program about that date. The machine gave me the number 584 and that took us directly to Istanbul -- or rather (at the time) to Byzantium. My first reaction was, Boy! Is that ever a lousy date!

The Roman empire was coming apart. Christianity was mired in politics. China had been through four hundred years of civil war. It'd settle down again, but not until the next century. The Prophet Mohammed was just fourteen. His followers would build a great civilization, but that too was to be later. Right now we hovered between the old world and the new.

The center of civilization was the city of Byzantium, today's Istanbul. Byzantium had built a great wall against the West and it gazed East across the Bosporus. Thus armored, it was becoming a static, closed world. Yet that's the place to look for inventive energy in 584 AD.

The great architect/inventor of that age was Anthemius of Tralles. He had died half a century earlier. His finest work was the cathedral of Hagia Sofia, or Holy Wisdom. He finished it in 527, but an earthquake soon damaged it. The rebuilt cathedral -- the one standing today -- was finished in 558.

If you've ever been in Hagia Sofia, you've been hit by an overwhelming sense of interior space. The partial domes rise one upon another. They carry a huge final dome at the top. Hagia Sofia ended an architectural era. It took the Roman arch to its limits, and the result is stunning. No one outdid it until Europe began making Gothic cathedrals five hundred years later.

Anthemius himself was wildly ingenious. He was a mathematician. He wrote a book on parabolic mirrors. One story tells of a quarrel between Anthemius and a neighbor named Zeno. Anthemius finally decided to teach the fellow a lesson. He created a steam-powered, artificial earthquake under the man's house.

But Anthemius had been dead for half a century in 584 AD. The only Byzantine invention we remember after his death was Greek Fire. It was a sort of napalm-like goo that the Byzantines flung at their enemies.

So our random date is interesting -- not for what it was, but for what it wasn't. It was a gap in human energy. It was a hiatus in the forward march. This random date -- this date I never would've chosen -- is a grim reminder. We, too, can lose our verve, our mental fight, our forward motion. And if we do, nothing remains but to wait for someone else to pick up the thread of civilization. (Theme Music outro)

Track 16: Wieliczka Sol (3:28): (Continuing trip music theme) So much to do and see in modern Istanbul! I'll leave you here for a few days while I take the car on to Karkow in Poland. That promises to be a fairly complex trip.

I've managed to get the necessary transit visas, and I want to see if I can pick my way through northern Bulgaria, then skirt the western slopes of the Carpathian Mountains through Rumania and a tip of the Ukraine, and finally enter southern Poland. I'll pick you up at the airport in Krakow when you arrive.

Krakow is a beautiful old historic city -- the city of Copernicus. But I want you to see one delight in particular. Just outside the city is the town of Wieliczka, where we find a remarkable salt mine.

Salt has strong symbolic importance in our lives because it's so essential. Tribes that live largely on milk and roasted meat don't need extra salt. But with our grain-based diets, we do. We say that nobility sits "above the salt" because, when salt was hard to come by, it was served only on the upper tables. The Bible calls a serious promise "a covenant of salt."

Most salt comes from either of two sources: The ocean contains a mixture of sodium chloride and other less palatable salts. Each of those salts comes out of solution at a different stage of evaporation so you can extract usable table salt from the ocean.

Rock salt is the other source, and it's much purer. It can either be mined directly from the earth or be processed from the natural brines that form when ground water flows through it. These high-grade salts give us the term, "salt of the earth."

Rock salt is the other source, and it's much purer. It can either be mined directly from the earth or be processed from the natural brines that form when ground water flows through it. These high-grade salts give us the term, "salt of the earth."

A huge natural deposit of rock salt lies under Wieliczka. The town itself is part of the Polish phrase, "The Great Salt Treasure." We know that salt was taken out of Wieliczka as early as 3500 BC.

That first salt came from saline springs. When Poland became a nation in the 10th century, these springs were already a major salt center. The Poles began underground mining of both rock salt and brine in the late thirteenth century. For a while, Wieliczka was home of the major natural resource of Poland.

The Wieliczka mine is still in use, and it's a marvel. It reaches eight hundred feet into the earth, with 150 miles of tunnels. As tunnels were left behind, they spoke to the miners' imaginations. Statues and tableaux have been carved from the living salt. Kings, trolls, and saints loom out of the darkness, larger than life. Chapels, hewn in the salt, range from small prayer stations to a great subterranean cathedral lit by crystal chandeliers.

One room is two hundred feet high, and its floor opens onto a lake of brine. In WW-II, the Germans used part of the mine to build airplane engines, safe from allied bombs. A large sanatorium lets respiratory patients breathe in the cool salt air. Seven hundred years of technique is on display in a great museum of mining technology. The mine even has its own post office.

Wieliczka is a monument, not just to human ingenuity, but to the symbolic power of the salt of the earth. It's a celebration of the unlimited imagination that makes any enterprise worthwhile. By the time we leave this strange fairyland, the open air seems drab by comparison. (Theme Music outro)

Track 17: Count Rumford In Munich (3:17): (Continuing trip music theme) On the road once more, this time to Munich. We pass Auschwitz, and stop to go through it. (We'd have to be less than human not to.) After that we continue in silence to Prague, a good place to spend the night.

We reach Munich in time for lunch, the next day. Munich is a wonderful old town and I want you to show you a very special place there. We go off to digest our schnitzels and sausages in the People's Park. That might sound to you like a holdover from the 1960s, but it's not.

This is a lovely two-mile-long natural preserve with trees and a river running through. It forms a huge part of the city. A Colonial American named Benjamin Thompson designed it in the late eighteenth century. Thomson had been raised in Woburn, Massachusetts, just before the American Revolution.

He wrestled out a homemade education in Boston and, when he was only eighteen, went off to Rumford, Massachusetts, as its new schoolmaster. He soon married a wealthy 31-year-old widow in Rumford. He also took up spying on the colonies for the British.

When the colonists learned what he was up to, he deserted his wife and a new daughter and fled to England. There he devoted himself to shameless social climbing. That eventually put him in a high-ranking position with the Bavarian court in Munich.

His life took on a new coloration in Bavaria. He used his technical insight to institute social reforms that were years ahead of their time. He devised public works, military reforms, and poorhouses. He equipped them with radical kitchen, heating, and lighting systems. He created that lovely People's Park.

When he was made a Count of the Holy Roman Empire he did a surprising thing. He took the name of the town he'd once fled -- the name of Rumford. And it is Count Rumford whom history remembers. He's most famous for experiments he made five years later while he was working with field artillery. He found that, by boring a cannon barrel under water with a blunt bit, he could heat the water to boiling and then keep it boiling.

People at the time thought that heat was an invisible fluid called caloric that flowed in and out of materials. Caloric, was the last of the old Aristotelian essences -- earth, air, water, and fire. It was supposed to be indestructible and uncreatable. Rumford's results flew in the face of the caloric theory. He made it clear that mechanical work could go on creating caloric as long as anyone might wish.

Rumford's story takes a last ironic turn. The French chemist, Lavoisier, who was beheaded during the French Revolution, had given caloric its name. When Rumford left Bavaria for England and France, he took up with Lavoisier's widow. Their four-year relationship ended in a short and disastrous marriage. Before the marriage Rumford crowed:

I think I shall live to drive caloric off the stage as the late Lavoisier drove away [phlogiston]. What a singular destiny for the wife of two Philosophers!

Count Rumford had, indeed, been instrumental in driving caloric off the stage, and setting a foundation for the first law of thermodynamics. But is it any great surprise that the marriage failed. (Theme Music outro)

Track 18: Johann Gutenberg In Mainz (3:17): (Continuing trip music theme) A half day's drive to the northwest brings us to a another small city, just west of Frankfurt. It is Mainz. This is where European history was turned upon its ear by an invention completed in 1455.

Johann Gutenberg was born here sometime during the 1390s and his invention has been your constant companion, all your life. Gutenberg's given name was Gensfliesch zur Laden. (Gutenberg was the name of his wealthy father's house.) His father worked with the ecclesiastic mint and Gutenberg grew up knowing the trade of goldsmithing.

Most of Gutenberg's early life is a mystery. His father moved to Strasburg in 1411. After that, he first surfaces in a 1436 lawsuit. A lady is suing him for breach of promise.

A 1439 lawsuit was even more interesting. Relatives of Gutenberg's recently deceased partner, Andreas Dritzehn, sued him. Gutenberg and Dritzehn had borrowed a lot of money for a development venture. Here the story grows interesting indeed. You see, Gutenberg didn't begin printing his great Bible until nineteen years later -- until 1455.

The top of a page St. Mark's Gospel from Gutenberg's 1455/6, 42-line Bible

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Library)

Gutenberg and Dritzehn's first venture had been to produce items for sale to pilgrims on the way to Aix-la-Chapelle. Those articles almost certainly included printed indulgences. Indulgences that had to've been printed by Gutenberg have turned up with dates that precede his great Bible.

In any case, Gutenberg and Dritzehn shrouded their venture in secrecy. Court records refer to purchases of lead and printing materials -- to forms and pieces that make sense only in terms of printing with movable type.

By 1449, Gutenberg's credit had worn thin in Strasburg. So he moved back to Mainz and began borrowing again. Finally, he borrowed eight hundred guilders from one Johann Fust. Eight hundred guilders was a huge lot of money, enough to buy a hundred cows or several small farms.

Seven years later he finished his Bible. By then he'd run his debt over two thousand guilders. That was the year that printing with movable type turned the known world upside down. It was the year Gutenberg redirected human history.

It was also the year Fust foreclosed on the now aging Gutenberg. Historians have weighed Fust's action ever since. He may have committed one of the smarmiest business deals in history. But maybe not. The secretive Gutenberg was probably diverting borrowed money into a separate venture. He was positioning himself to buy out Fust. More than likely, two hardball businessmen went nose to nose, with little love lost, and Fust won.

So Fust got the business. He also got Gutenberg's superb technician, Peter Schoeffer. In 1457, Fust and Schoeffer put out a Latin Psalter that Gutenberg had been working on secretly -- even before the Bible. From then on their names, not Gutenberg's, grace the lovely books they produced. So lovely! We find that the clock stops as we drift from one display case to the next, in the Gutenberg Museum, here in Mainz.

Fust and Schoeffer's Printers' Device from Juan de Torquema's Exposito Psalteri, 1476

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Library)

(Theme Music outro)

Track 19: The Bog Men (2:48): (Continuing trip music theme) Our journey now takes us straight north into Denmark, to the town of Silkeborg in Jutland. It's close to the Tollund Marshes and it offers us an astonishing window into Europe's iron age.

I want you meet a very old man here -- someone who'll tell us important things about life and death. We don't know his name, only that he came from out of the Tollund marsh. His face is composed. It has an eerie serenity. We'd like to chat with him. What would he tell us about the birds, the low gray rain clouds or last year's barley crop? But he's dead now. You'd think he'd died just the other day. In fact, he's seventeen centuries old.

The Tollund Man. Image courtesy of the Silkeborg Museum

The Tollund Man is neither the first nor the last body given up by the Danish peat bogs. Peat cutters have found hundreds of them. They're iron-age villagers who died during the days of Roman rule. The bog waters, saturated with just the right soil acids, have preserved them with no embalming.

We look at that gentle face and wonder why he died. Then we lift a lump of peat from behind his head. To our horror, we find a leather rope around his neck. Someone strangled him before they threw him into the swamp. But why! Was he a victim -- a thief?

Archaeologists go to work. They use forensic medicine, botany, carbon dating, and more. They're puzzled by what they find in the man's stomach. He ate his last meal the day before he died. It was a gruel made of grain and other plants. These people weren't vegetarian. Yet he'd eaten no meat recently.

The gruel was a witches' brew of winter plants. So we make our own gruel by the same recipe. It tastes awful. We look at last meals from other bog people. One ate a gruel made from sixty-three different plants.

So the plot thickens. We ask how the others died. Most were hanged, drowned, or had their throats cut. The same bogs yield coins, legs of meat, and pottery. People aren't the only valuables in the bogs.

Add all this up. Combine it with a few old writings. And our Tollund man seems to have been sacrificed to some goddess of the harvest.

Many bog people have well-preserved hands and feet. Many show no signs of the toil that began and ended peasant lives in old Northern Europe. If this was a sacrificial death, it was one the wealthy shared with the poor. They probably chose our Tollund man by casting lots.

So this ancient man with the gentle face reaches out to tell the continuity of life through death. And a Danish poet writes,

Yet they were made of earth and fire as we,

The selfsame forces set us in our mould;

To life we woke from all that makes the past.

We grow on Death's tree as ephemeral flowers.

(Theme Music outro)

Track 20: Raising The Vasa (3:44): (Continuing trip music theme) We want to look at one more archeological site. This one is in Stockholm. The trip will be interesting since two heroic bridges were recently built, and they'll let us stay in the car all the way.

First we drive 140 miles east. We pass through Odense, cross the Nyborg Bridge, and continue to Copenhagen. We'll spend the night there. The next day we'll cross the new Øresund Bridge from Copenhagen, to Malmo, Sweden. Then it's another four hundred miles to Stockholm. (Once in Sweden, distances become positively Texan.)

Just as the bogs of Denmark held history, so too does the harbor of Stockholm. We've come here to see a grand ship, badly built, which (like the Tollund Man) now serves as a remarkable time capsule.

King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden ruled the Baltic Sea in 1628 -- the year he launched the warship Vasa. Vasa looked very much like its contemporary, the Mayflower; only it was twice as big.

Vasa was a two-hundred-foot gun platform. She had two rows of brass cannon -- sixty-four in all. She was wildly ornate. Her stern was a glory of brightly-painted carved figures of knights and mythical beasts. She could've sailed right out of a child's storybook.

Crowds cheered as Vasa crossed the harbor on her maiden voyage. Then wind filled her sails, and she began to heel. She leaned and leaned until her lower gun ports were under water. Water rushed in. She foundered and sank. She carried fifty people to their deaths a hundred feet below.

The King, it seems, had meddled in the design. Vasa was designed for only one row of guns. He'd ordered a second row of 2500-pound brass cannon to be added. There was room in the hull for only 121 tons of stone ballast. That was far too little. Vasa would be top-heavy, and the shipbuilders all knew it.

Thirty-five years later, in 1663, a Swedish inventor named Albrect von Treileben came on the scene with a new diving bell. He managed to go down and get most of the expensive cannons. The rest of Vasa sat in the mud in the cold, low-salt, Baltic Sea, largely forgotten, in a remarkable state of preservation.

In 1956 the great wreck-hunter Anders Franzen found Vasa on the bottom of Stockholm Harbor. He realized he could actually bring it up whole, though it would be a Herculean job.

Divers went down and tunneled through the muck under the hulk, dragging cables after them -- fearing a cave-in every moment. They attached the cables to a system of floats above. By blowing water out of the floats they managed to lift Vasa a few feet at a time. They stair-stepped her up to slightly shallower sea beds, over and over, eighteen times.

By 1959 Vasa finally surfaced, and years of careful reclamation work began. Skeletons of the old crew lie where they died. One has been crushed under a gun carriage. The mouth of another opens in a terrible screaming rictus. Three cannons had lain beyond the reach of seventeenth-century divers. Now they rise from the mud along with treasure, art, and a microcosm of seventeenth-century daily life. Just as in the Tollund Marshes, life and death rise out of the mud together.

And we sort the many ironies of Vasa. She was glorious in her finery, yet the crew lived in near cesspool conditions. It cost more to reclaim her than to build her in the first place.

But the greatest irony of all is that Gustavus Adolphus's technological blunder created a time capsule to serve history long after old naval wars had been forgotten. (Theme Music outro)

Track 21: The Queen Mary (3:53): (Continuing trip music theme) We've seen many things upon our long journey. It would be a pity if we couldn't find one more adventure on the way home. So we turn in our car and fly back to England

But now we'll do a bit of magic and turn the clock back sixty-five years. We've booked our passage home on a wonderful old ship, the Queen Mary.

A few years back I had the opportunity to visit the now-permanently docked Queen of the ocean. It was the largest ship I'd ever entered. I walked her endless hallways that evening, and supped in one of her dining rooms. I fulfilled at least part of a childhood dream that evening.

I was only three when the Queen Mary was launched. Her statistics played tag with the French Normandie, but she was the grandest thing in the water nevertheless. She was an icon of my childhood. The words Queen Mary meant size, elegance and beauty.

Her launch announced England's emergence from the depression. The poet, John Masefield, regarded that great mountain of iron with a keen sense of the engineer's heart. He wrote,

For ages you were rock, far below light,

Crushed, without shape, earth's unregarded bone. . . .

Then Man in all the marvel of his thought,

Smithied you into form of leap and curve;

And took you, so, and bent you to his vast, Intense great world of passionate design.

So she came to life: eighty thousand tons; almost as long as the Empire State Building; two thousand passengers served by a thousand crew members; sluicing ahead at thirty-six miles an hour. Masefield goes on:

Parting the seas sunder in a surge,

Shredding a trackway like a mile of snow.

There were still problems, of course. She suffered a nasty rolling motion. That wasn't corrected until William Denny invented a special damping stabilizer in 1957.

During WW-II she converted to a troop ship. Instead of two thousand passengers she now carried almost sixteen thousand soldiers. At first men died of heat exhaustion when her non-air-conditioned hull entered the Indian Ocean. Then, in 1942, that siren Queen lured 331 men to their deaths. Officers on the English escort cruiser Curaçao wanted to take pictures as the Queen ran her zig-zag submarine evasion pattern. The Curaçao got too close. Suddenly she was in front of the great liner. Queen Mary sliced her in two like a pat of butter.

Still, despite those horrors, the Queen Mary helped shorten a terrible war. Then, refitted as an ocean liner in 1947, she served another twenty years. She sailed four million miles and carried two million passengers.

But she couldn't compete with transatlantic jets. In 1967, she and another great technological dinosaur retired to a dock in Long Beach, California. She and Howard Hughes's Spruce Goose flying boat were both on display there until the Spruce Goose was relocated in Oregon.

The Queen Mary still functions. Now she's a grand floating hotel. And, that evening I visited her, I strolled through miles of art deco elegance. For a moment I knew what it might've been to be wealthy in 1935. For a few hours I savored the last hurrah of a technology that's still not quite ready to die.

And that, good friends, is why we finish our long journey of the imagination, not today, but sixty-five years ago. I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work. (Theme Music outro)

Track 2:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1362.

Angelucci, E., World Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft: From Leonardo da Vinci to the Present. New York: Crown Publishers, 1982.

Markham, B., West with the Night. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1983 (1st ed., 1942.)

Track 3:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 578.

Derriman, P., Bog Irish. Qantas Airways, July/August, 1991, pp. 16-22.

The Ceide Fields home page is: http://homepages.iol.ie/~stmrysba/ceide2.htm

Track 4:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 459.

Glick, T.F., Cob Walls revisited: The Diffusion of Tabby Construction in the Western Mediterranean World. Humana Civilitas: Sources and Studies Relating to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Vol. I. On Pre-Modern Technology and Science. (B.S. Hall, D.C. West, eds.) Malibu: Undena Publications, 1976.

Yeats, W.B., The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats. Definitive edition, with the author's final revisions. New York: Macmillan Co., 1956.

The Builders: Marvels of Engineering (Elizabeth L. Newhouse, ed.). Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, Book Division, 1992, pp. 226-229.

Track 5:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1275.

Thomas, B., Merthyr Tydfil and Early Ironworks in South Wales. The Company Town: Architecture and Society in the Early Industrial Age. (John S. Garner, ed.) New York: Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 17-41.

Track 6:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 627.

Howse, D., Greenwich Time and the Discovery of Longitude. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980, Chapter 2.

Track 7:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 959.

The book I purchased outside Rouen Cathedral was: Regnault, P., Les Entretiens Physiques d'Artiste et d'Eudoxe, ou Physique Nouvelle en Dialogues, Qui Renferme Precisément ce qui s'est Découvert de plus Curieux & de plus Utile dans la Nature. Vol. 3, 7th ed., revised and corrected. Paris: Chez David et Durand, 1745.

Track 8:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 958.

Miller, M., Chartres Cathedral (with photos by S. Halliday & L. Lushington). New York: Riverside Book Co., 1985.

Track 9:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 577.

For a nice account of the Poitiers Baptistry, see: Clark, K., Civilisation. New York: Harper & Row, 1970, Chapter 1. (See also the first installment of Clark's television series of the same name.)

Track 10:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 910.

Burke, J., The Day the Universe Changed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985, Chapter 2, "In the Light of the Above."

Track 11:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 375.

Kerisel, J., A Few Hidden Errors in Medieval Architecture. Down to Earth. Boston: A.A. Balkema, 1987.

Track 12:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1345.

History of World Architecture (Luigi Nervi, ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1974. This offers a good deal of material on the Pantheon. See the Index.

Rivoira, G. T., Roman Architecture. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1972, Chapter VIII, Hadrian.

See also Encyclopaedia Britannica articles on Pantheon and Hadrian.

Track 13:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1348.

Götze, H., Castel del Monte: Geometric Marvel of the Middle Ages. New York: Prestel, 1998.

Willemsen, C. A., and Odenthal, D., Apulia: Imperial Splendor in Southern Italy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers, 1959.

Godfrey, M., Italian Architecture up to 1750. New York: Taplinger Publishing Co. Inc. 1971.

See also various encyclopedia listings under Frederick II.

And here is an interesting page with information about computer-graphics representations of the Castel del Monte: http://www.prz.tu-berlin.de/~joe/castel/castel.html

Track 14:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 886.

The Houston Symphony, the Houston Symphony Chorus, and the Fort Bend Boys Choir performed Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, Op. 66, on Sunday, November 14, 1993 at Jones Hall in Houston, Texas. Britten's text is woven from poems by Owen and elements of the Latin Requiem Mass.

Track 15:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 543.

Material for the segment on Byzantium and Hagia Sofia was assembled from a variety of conventional sources. See, e.g., White, L., Medieval Technology and Social Change. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. 89-90. See also any of a variety of detailed historical time-lines. For example, Chronicle of the World. (J. Bourne and J. Bourne, eds.) Ecam Publications, 1989.

Track 16:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 297.

Wieliczka Solny Skarb. Krakow: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. 1984. See also the website: https://www.kopalnia.pl/english/trasa.htm

Track 17:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1165.

Brown, S.C., Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981.

Track 18:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 753.

Scholderer, V., Johann Gutenberg: The Inventor of Printing. London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1963.

Track 19:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 487.

Glob, P.V., The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved (Tr. R. Bruce-Mitford). New York: Cornell University Press, 1969. The verse quoted in the text is by Thogar Larsen. Glob uses it as the frontispiece of his book. Glob dedicates his book to the names of fifteen girls. It seems he wrote it in answer to a letter from a class in an English girls' school. They'd written to find out more about the bog people.

For more on the Tollund Man, see the Silkeborg Museum home page: http://www.silkeborgmuseum.dk/english/index.html

Track 20:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 873.

For information about the remarkable Øresund Bridge, visit the web site: https://www.oresundsbron.com/

Ohrelius, B., Vasa: The King's Ship (tr. M. Michael). Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1952 and 1962.

Franzen, A., The Warship Vasa: Deep Diving and Marine Archaeology in Stockholm. Stockholm: Norstedt and Bonnier Pubs., 1961.

Kvarning, L-A., Raising the Vasa, Scientific American, October 1993, pp. 84-91.

Track 21:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 697.

Hutchings, D.F., RMS Queen Mary: 50 Years of Splendour. Southampton: Kingfisher Publications, 1986.

The QUEEN MARY: A Book of Comparisons. (This is a reprinting of a brochure published by the Cunard White Star Line when the Queen Mary was still young. I obtained mine in the Queen Mary bookstore.)

The "Spruce Goose" has subsequently been moved to the Evergreen Aviation museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

For more on the Queen Mary, see the website, http://www.queenmary.org/