Flying Across the Atlantic

Today, we fly the Atlantic. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

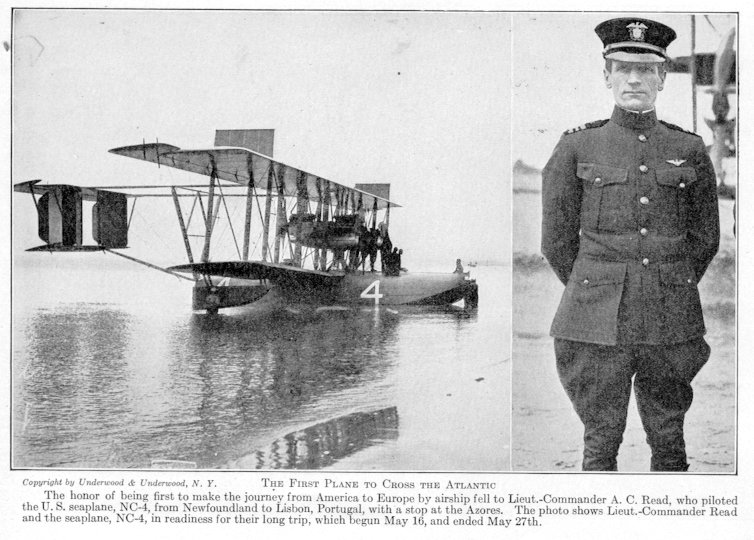

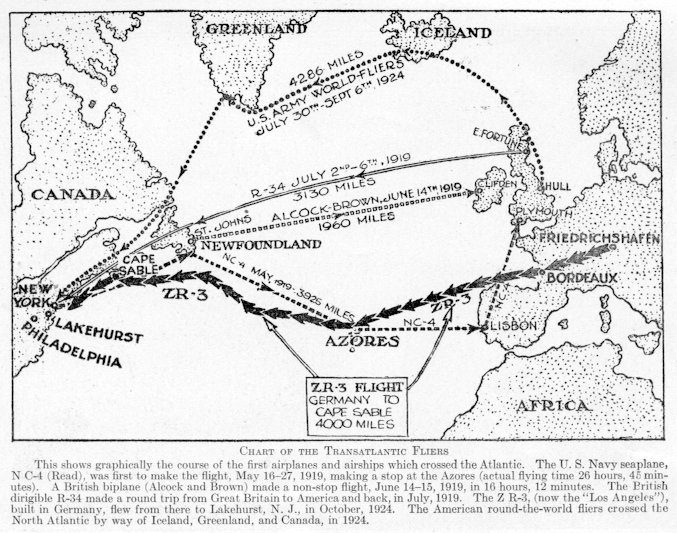

Dozens of people had flown the Atlantic Ocean by 1927. Then Lindbergh made his historic nonstop flight we forgot about all that went before him. The first flight was made in May 1919 from New York to Plymouth, England. It was done in a six-man, four-engine, Navy flying boat which stopped in the Azores and Lisbon on the way. That same month, Raymond Orteig of New York City offered a $25,000 prize for the first nonstop airplane flight from New York to Paris. Just one month later, Alcock and Brown flew a two-engine airplane nonstop from St. John's, Newfoundland to Clifden, Ireland.

In July 1919 a British dirigible flew from England to New Jersey and back. Then, in 1922, two Portuguese aviators, Cabral and Coutinho, flew a single-engine British seaplane from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. That's a longer flight than Lindbergh's but there's a catch. They didn't just stop over on the way; they actually changed airplanes on a small Atlantic island.

More flights from New York to England followed in 1924. And in 1924 a Zeppelin dirigible flew from Friedrichshaven to Lakehurst, New Jersey. Finally, 1927 saw seven transatlantic heavier-than-air flights, of which Lindbergh's was the third.

So what was so special about Lindbergh's flight? Well, it was the longest, nonstop, heavier-than-air, transatlantic flight and it was the first solo crossing. That's how he picked up the nickname, The Lone Eagle. And his flight finally fulfilled the difficult specific conditions of the Orteig prize which had, by then, been waiting more than eight years.

If you've ever flown to Europe, you know how much longer it takes to get back. Prevailing west winds oppose you on the return. No one managed a solo heavier-than-air flight from East-to-West until 1932. Then a pilot named James Mollison got from Ireland to New Brunswick. It was 1936 before Beryl Markham finally flew from England to the Canadian mainland. (She told about that in a beautifully written book, West by Night.)

Hers was the last step that had to be taken before commercial transatlantic flights began in the late 1930's -- twenty years after the first transatlantic crossing and thirty-five years after the Wright brothers. Still, Lindbergh's flight is what that riveted public awareness; and it's worth mentioning his airplane. Lindbergh was a determined airmail pilot who finally found a like-minded designer at the tiny Ryan Airplane Company. Ryan specially built the Spirit of St. Louis for Lindbergh in just two months time.

They called him Lucky Lindy. But his luck was the making of many people. It was finding the right engineer at the right time. It was the luck of having a great parade of risk-taking and courage before him. But the word luck does not apply to the courage and focused intensity Lindbergh brought to the one flight we remember.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Angelucci, E., World Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft: From Leonardo da Vinci to the Present. New York: Crown Publishers, 1982.

Markham, B., West with the Night. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1983 (1st ed., 1942.)

This is a substantially revised version of Episode 37.

For a full-size image click on either thumbnail above

On the left: The NC-4 airplane which made the first flight across the Atlantic. On the right: A map of several Atlantic flights prior through 1924.

Images of transAtlantic flight in the 1923 edition of The World Book of Knowledge (probably edited subsequently)