Tabby and Cob

Today, I would a cabin of mud and wattles make. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Years ago, I taught for a season in Southwest England. We lived in an old Anglo-Saxon town -- in a thatch and cob cottage. It'd stood for 500 years. Thatch is the thick woven straw that makes the roof. The walls are a mixture of clay and straw called cob, or sometimes tabby.

The material varies, as well as the name. Cob, or tabby, is a poor man's masonry. To make it, you mix a structural material -- like straw, corn stubble, or oyster shells -- with clay or earth. It makes a solid building material. In one form, we daub mud onto wattles. Wattles are twigs woven together.

Cob was probably invented by the Phoenicians. The Carthaginians learned it from them. The Romans learned to make cob from the Carthaginians. Later, the Romans invented concrete. After that, we find walls of concrete cob that still stand today. Cob went from Rome to Spain, and into Europe and England.

The written record of tabby and cob is confusing because it has to be reinvented in every land. Mud, clay, and all the filler materials occur in such variety that the stuff defies identification. In the early 1500s, building on Tenerife expanded rapidly. Tabby was the best low-cost building material. Records say that tabby workers who came from Spain didn't know what they were doing. In fact, it simply took a while to invent techniques for using local materials.

So I go back to that wet winter in Devon, living in a cob house. One night at supper, we heard a chilling PLOP. We turned and saw a huge scar on the wall. A square foot of clay had fallen out and splashed over the floor. Cob, it seems, must be patched regularly. And so it had been for 500 years before we came.

Mud and filler composites are among the oldest and most widely used materials on earth. We live in boxes of concrete and glass -- wood, brick, and steel. We forget the potential, even today, of odd mixtures of materials. We forget mud and straw.

The poet, Yeats, dreamt of going back to Inisfree -- to that tiny wild island in a lake near Sligo, in Ireland. He dreamt of creating a place to be, from mud and wattles. I doubt he ever really tried the trick. Cob may be a poor man's masonry, but it's not a poor craftsman's enterprise.

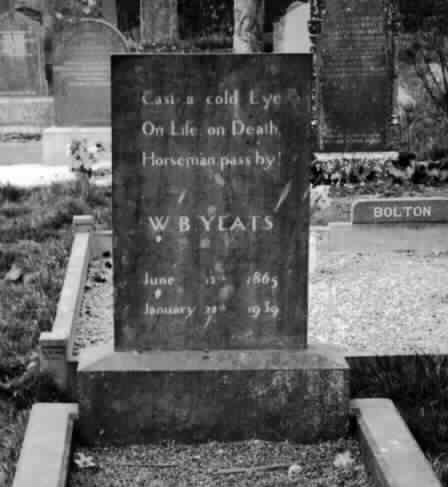

Yeats is buried near Inisfree, where he dreamt about shaping clay. When he passed back into earth, he left this on his head stone: "Cast a cold Eye, On Life on Death, Horseman pass by." We forget the old walls of mud & wattles -- of tabby and cob. Yet they are the spit and clay that've formed our civilization.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Glick, T.F., Cob Walls revisited: The Diffusion of Tabby Con- struction in the Western Mediterranean World. Humana Civilitas: Sources and Studies Relating to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Vol. I. On Pre-Modern Technology and Science. (B.S. Hall, D.C. West, eds.) Malibu: Undena Publications, 1976.

(I am grateful to Pat Bozeman, Head of Special Collections, UH Library, for drawing my attention to source and making her uncatalogued copy of it available to me.)

Yeats, W.B., The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats. Definitive edi- tion, with the author's final revisions, New York: Macmillan Co., 1956.

The complete text of the Yeats poem to which I allude, but from which I do not quote, is:

THE LAKE ISLE OF INISFREE

I will arise and go now, and go to Inisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honeybee,

and live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight's all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet's wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart's core.

William Butler Yeats

(Photo by John Lienhard)

Yeats' Isle of Inisfree

(Photo by John Lienhard)

Yeats' headstone in Sligo