The Pantheon

Today we build a big room. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

You might say the fundamental problem of architecture is creating interior space. Igloos and wigwams offer clever means for gaining unobstructed indoor space. Houses offer more space, but that space has to be broken up into rooms. That's okay, because it affords some privacy. The large unobstructed space offered by Indian and Neolithic long houses was awkwardly long and narrow.

How then to create indoor spaces, as wide as they are deep, spaces for large gatherings: temples, churches, closed arenas, assembly halls? The Egyptians didn't manage it. Greek architecture didn't provide that sort of indoor space either. The Romans finally succeeded because they had the concept of the Roman arch.

In 25 BC, Agrippa dedicated the Pantheon to all the gods. The word Pantheon means of all gods. But that didn't incur proper divine protection for the wooden building against destructive fires in 80 and again in AD 110. Hadrian was emperor of Rome during the second fire. He was an extremely effective leader, a great builder, and a fine architect.

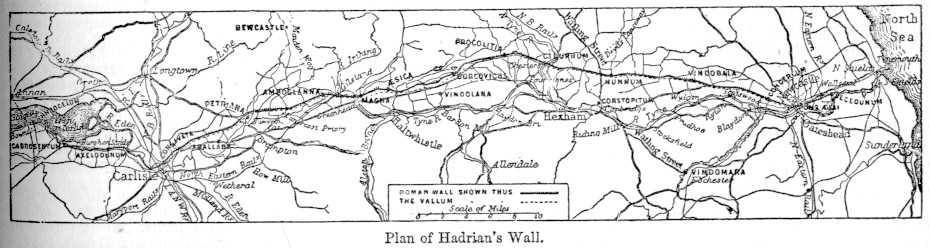

It was under Hadrian's rule that Hadrian's Wall across Northern England was begun. It was under Hadrian, and with his involvement as an architect, that a new Pantheon was erected in AD 126. And it became one of the architectural landmarks of all time.

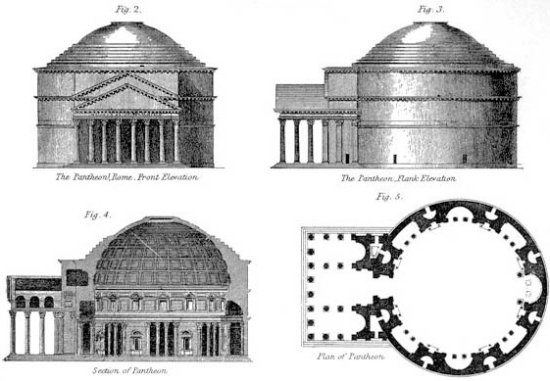

The Pantheon is a large pillbox of a building with a square classical front on one side. You enter that front, and it leads you into the largest domed space the world would see until 1800 years later. The central chamber is 142 feet in diameter, and its top rides 142 feet above the floor. But that's not all.

This is no Gothic arch of stacked stone. It's a far more modern construction. The dome is cast concrete, decorated with an elaborate waffle pattern on the inside. At the top is another surprise. The center is a 27-foot hole -- an oculus, or eye, which carries light into that great inner space. The 20th-century American artist James Turrell has been using that idea. Turrell has created many structures with apertures in their roofs to catch the shifting lights of day and of the half light in just the same way.

The cast concrete dome seems to've originated with Hadrian. Previous attempts to build with concrete had warned the Romans to make serious changes in the way they used concrete. So the Pantheon sits on a foundation ring 15 feet deep and 24 feet wide and is buttressed by concentric outer support rings. The shell of the huge dome not only tapers from a thickness of 22 feet down to five feet. But the engineers have also graded the density of the concrete so the material is lighter near the top.

During the seventh century, in now-Christianized Rome, this temple to all gods became the Rotunda of Santa Maria. In that role it may command less attention than Notre Dame or St. Peter's. But ask anyone who's taken time to see that great skylit hemispherical space. They will tell of being caught off-guard by its surpassing ancient glory.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The Builders: Marvels of Engineering (Elizabeth L. Newhouse, ed.). Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, Book Division, 1992, pp. 226-229.

History of World Architecture (Luigi Nervi, ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1974. This offers a good deal of material on the Pantheon. See the Index.

Rivoira, G. T., Roman Architecture. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1972, Chapter VIII, Hadrian.

See also Encyclopaedia Britannica articles on Pantheon and Hadrian.

Views of the Pantheon from the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica

A section of Hadrian's Wall today.

(Photo courtesy of Kathy Kopacek)

For a full-size image, click on the thumbnail.

Plan view of Hadrian's Wall from the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica.