Castel Del Monte

Today, we wonder why a castle was built. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

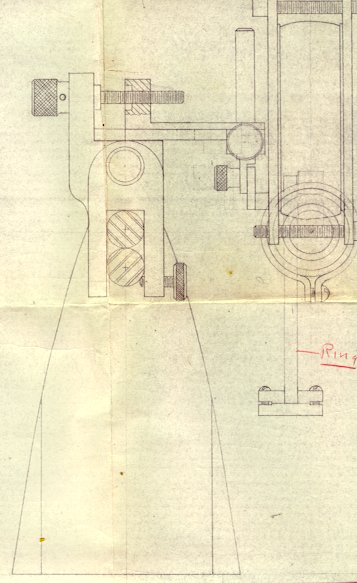

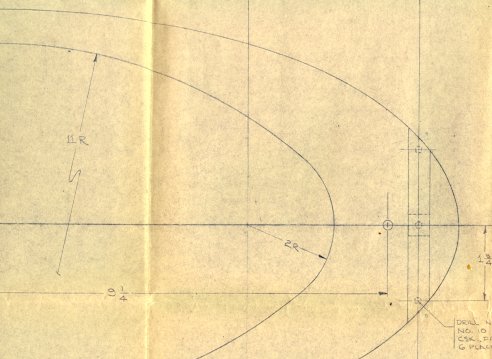

Just north of the heel in Italy's boot sits an odd gem, the Castel Del Monte. It reminds me of designing an apparatus to be used in semiconductor research while I was in the army. I felt the need of intellectual elbow room, so I contrived to build every conic section into the apparatus. Around the functional parts I shaped an array of lovely, purposeless, soul-satisfying curves.

The Castel Del Monte was designed in a similar way by a 13th-century emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick II. Frederick was a scholar and an architect. He knew Arabic as well as Latin, and he was influenced by all he'd seen on a crusade into the Arabic world. He founded the University of Naples. He was also a friend to the great mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, who introduced the Arabic representations for zero and ten into European calculation.

Frederick's architecture is marked by strong planar surfaces with circular towers and half-towers. It's all very geometric and even willful. In the words of one architectural historian, it makes no concession to the land around it. And the imprint of abstract Islamic ornamentation runs through Frederick's work.

He built the Castel Del Monte in the 1240s. In a land were snow is rare, it reminds us of the fractal shape of snowflakes. It's a perfect octagon, 123 feet across, with an octagonal center court. Octagonal towers on each corner carry the octagonal theme downward in scale. Its floor plan reflects octagonal Islamic tile work. It makes me think of my own play with conic sections. It's an eye-catching exercise in geometry that outruns any purpose.

So why did Frederick build it? His castles all over Sicily and southern Italy were certainly meant to express imperial power. But in this building we see something more. It's a dark and closed place inside, with a form so coolly mathematical as to be beautiful. A contemporary looked at it and wrote Stupor mundi et immutator mirabilis. That was more an astonished outcry than a sentence. It meant something like, Amazed world -- wondrous novelty!

Frederick's son Manfred died in battle in 1266, and Frederick's three grandsons were condemned to life imprisonment in the Castel del Monte. One escaped after 30 years, only to disappear into Egypt. And that dreary footnote is the only role in history I've been able to find for this 760-year-old exercise in geometry.

This beautiful castle chokes on self-indulgence. When I went back to Fort Monmouth in the 1960s and found my apparatus still in use, it was an enormous relief. My own self-indulgence hadn't been quite been enough to've made the design useless. Any good design must have the designer's personality written upon it. But it should be etched lightly. It should be there, but only hovering -- only an aura.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Götze, H., Castel del Monte: Geometric Marvel of the Middle Ages. New York: Prestel, 1998.

Willemsen, C. A., and Odenthal, D., Apulia: Imperial Splendor in Southern Italy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers, 1959.

Godfrey, . M., Italian Architecture up to 1750. New York: Taplinger Publishing Co. Inc. 1971.

See also various encyclopedia listings under Frederick II.

My thanks to Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Librarian, for suggesting the episode and providing most of the source material.

From A history of Architecture in Italy, Vol. II, 1901

Click on the thumbnail above to see the full size image.

Details from working drawings by JHL for an apparatus to measure magnetic

properties of semiconductor materials, Signal Corps Engineering Labs.

Left: Sample holder bracket, Right: part of the upper bed of the apparatus