A Dark Age

Today, a first step away from the Dark Ages. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

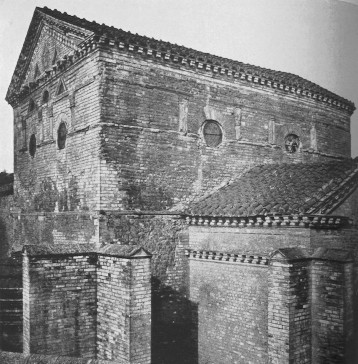

We're in Poitiers, in central France, in front of a 7th-century baptistery. This little stone church is only a dim memory of Roman architecture. Its arches, pillars, and lintels are only decorations built into the walls. Their original structural purpose has been lost. What does it mean?

You and I were raised on the idea that a Dark Age lay between the Roman Empire and a new European civilization. Now historians say Medieval Europe wasn't nearly so dark. From the 10th to the14th centuries, civilization underwent a rebirth. But earlier -- in the near wake of Rome -- things really were pretty bad. As the Roman empire closed down, her northern reaches faded back into the forests.

An old Anglo-Saxon poet looks at remains of the old Roman glory. He looks at husks of once great buildings and says,

A wise man may grasp how ghastly it shall be

When all this world's wealth standeth waste

Even as now, in many places over the earth,

Walls stand wind beaten,

Heavy with hoar frost; ruined habitations ...

The maker of men has so marred this dwelling

That human laughter is not heard about it

And idle stand these old giant works.

So, for a while, Northern Europe barely subsisted. Marauding Vikings and nomads swept across it. Primitive peasants lived in mud huts. They looked at those great ruins like so many dinosaur bones.

Many of the great Roman aqueducts, ampitheatres, and arches still stand. But they made little sense to people for whom life was a brief exercise in survival. Rome had built all that on the backs of slaves. One thing we can give the Northern European peasants is that they were not slave-keepers. They would need a power source before they'd ever rise above mere subsistence.

Eighth-century France finally began giving us new power sources. First, farmers learned to use horses. Then they gained full control of water power. After that, they too started building a civilization -- one that would soon surpass Rome.

But now we stand in Poitiers, looking at this crude building -- begun in the 5th century and remodeled in the 7th. It is a valiant attempt to start a new life with grace and beauty in it. Like the old Roman structures, it was meant for posterity. And it does still stand today.

But they hadn't got the hang of it -- not yet. Five hundred years later they'd build Gothic cathedrals and more. But we gaze at this pretentious little church -- this determined attempt to leave the forest. And it speaks a bold, roughhewn grandeur of the inventive spirit that I find more moving than Notre Dame -- or the great coliseums.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Clark, K., Civilisation. New York: Harper & Row, 1970, Chapter 1. (See also the first installment of Clark's television series of the same name.)

From Sturgis's A history of Architecture, Vol. II, 1909 Image courtesy of the UH Art and Architecture Library

The Poitiers Baptistery, formally called The Temple of St. Jean