Wieliczka Sol

Today, we draw more than salt from a salt mine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Salt has strong symbolic importance in our lives because it's so important. Tribes that live largely on milk and roasted meat don't need it. But our grain-based diets do. We say that nobility sits "above the salt," because when salt was hard to come by, it was served only on the upper tables. The Bible calls a serious promise "a covenant of salt."

Most salt comes from either of two sources. The ocean contains a mixture of sodium chloride and other less palatable salts. Each comes out of solution at a different stage of evaporation, so you can extract usable table salt from the ocean.

Rock salt is the other source, and it's much purer. It can either be mined directly from the earth or be processed from the natural brines that form when ground water flows through it. These high-grade salts give us the term, "salt of the earth."

A huge natural deposit of rock salt lies just outside the old Polish capital of Krakow in the town of Wieliczka. Its name is part of the Polish phrase, "The Great Salt Treasure." We know salt was taken out of Wieliczka as early as 3500 BC.

Its first salt came from saline springs. When Poland became a nation in the 10th century, these springs were already a major salt center. The Poles began underground mining of both rock salt and brine in the late 13th century. For a while it was the major natural resource of Poland.

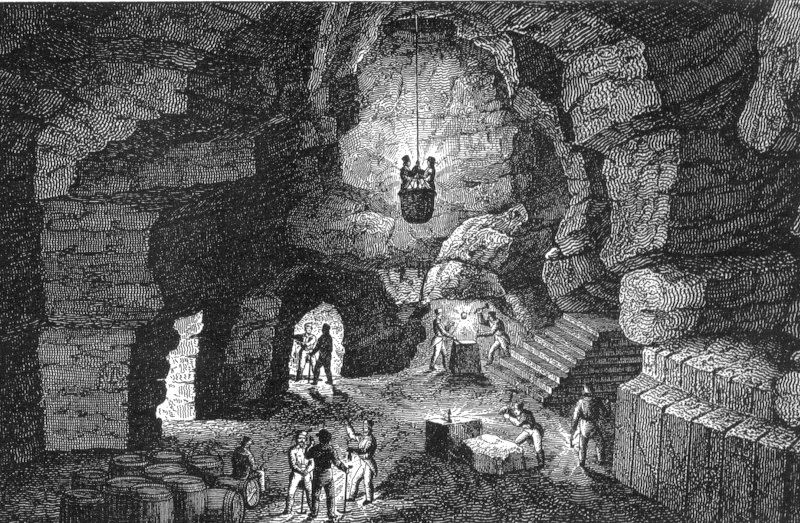

The Wieliczka mine is still in use, and it's a marvel. It reaches a thousand feet into the earth, with 150 miles of tunnels. As the tunnels were left behind, they spoke to the miners' imaginations. Statues and tableaux have been carved from the living salt. Kings, trolls, and saints loom out of the darkness, larger than life. Chapels hewn in the salt range from small prayer stations to a cathedral lit by crystal chandeliers.

One great room is two hundred feet high, and its floor opens onto a lake of brine. In WW-II, the Germans used part of the mine to build airplane engines, safe from allied bombs. A large sanatorium lets respiratory patients breathe in the cool salt air. 700 years of technique is on display in a great museum of mining technology. The mine even has its own post office.

Wieliczka is a monument, not just to human ingenuity, but to the symbolic power of the salt of the earth. It's a celebration of the unlimited imagination that makes human enterprise worthwhile. By the time you leave this strange fairyland, the open air seems drab by comparison.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Wieliczka Solny Skarb, Krakow: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. 1984.

See also the website: http://www.cyf-kr.edu.pl/wieliczka/

This episode has been greatly revised as Episode 2154.

A 19th-century woodcut of the Wieliczka mines

A salt crystal from Wieliczka (scanned at twice actual size)