Johann Gutenberg

Today, a detective story about the invention of the printing press. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Johann Gutenberg was born in Mainz sometime during the 1390s. His given name was Gensfliesch zur Laden. Gutenberg was the name of his wealthy father's house. His father worked with the ecclesiastic mint. Gutenberg grew up knowing the trade of goldsmithing.

Most of Gutenberg's early life is a mystery. His father moved to Strasburg in 1411. After that, he first surfaces in a 1436 lawsuit. A lady is suing him for breach of promise.

A 1439 lawsuit was even more interesting. Relatives of Gutenberg's recently deceased partner, Andreas Dritzehn, sued him. Gutenberg and Dritzehn had borrowed a lot of money for a development venture. Here the story grows interesting indeed. You see, Gutenberg didn't produce his great Bible until twenty years later -- until 1456.

Gutenberg and Dritzehn's first venture had been to produce items for sale to pilgrims on the way to Aix-la-Chapelle. Some historians believe those articles included printed indulgences.

But we don't know for sure. They shrouded the venture in secrecy. The court records refer to purchases of lead and printing materials -- to forms and pieces that make sense only in terms of printing with movable type.

By now Gutenberg's credit had worn thin in Strasburg. So he moved back to Mainz and began borrowing again. Finally, he borrowed 800 guilders from one Johann Fust. 800 guilders was a huge lot of money, enough to buy 100 cows or several small farms.

That was in 1449. In 1456, he finished the great Bible. By then he'd run his debt over 2000 guilders. That was the year that printing with movable type turned the known world upside down. It was the year Gutenberg redirected human history.

It was also the year Fust foreclosed on the now aging Gutenberg. Historians have weighed Fust's action ever since. He may have committed one of the smarmiest business deals in history.

But maybe not. The secretive Gutenberg was probably diverting borrowed money into a separate venture. He was positioning himself to buy out Fust. More than likely, two hardball businessmen went nose to nose, with little love lost, and Fust won.

So Fust got the business. He got Gutenberg's superb technician, Peter Schoeffer, as well. In 1457, Fust and Schoeffer put out a Latin Psalter that Gutenberg had been working on secretly -- even before the Bible. From then on their names, not Gutenberg's, grace the lovely books they produced.

Still, it is the wild, unstable inventor Gutenberg that we thank for the gift of type today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Scholderer, V., Johann Gutenberg: The Inventor of Printing. London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1963.

For more on Gutenberg, see Episodes 216, 628, 756, 894, and 992.

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Fust and Schoeffer's Printers' Device from Juan de Torquema's Exposito Psalteri, 1476

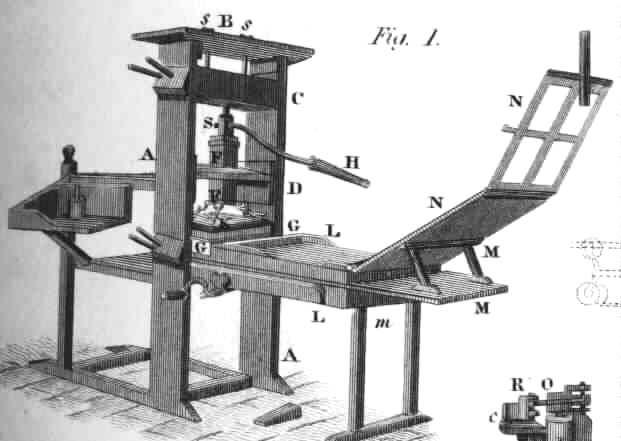

From Appleton's Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics, 1892

A typical Gutenberg-style press