Miss Columbia

by Andrew Boyd

Today, Mr. or Miss? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The appellation "Uncle Sam" traces its roots to Samuel Wilson of Troy, New York. Wilson packed barrels of meat for the army during the War of 1812, stamping them "U.S." for United States. But troops called them Uncle Sam's rations. A local paper covered the story, and the name stuck.

However, long before Uncle Sam was another figure who symbolized America: Miss Columbia. The name evolved as a feminization of Christopher Columbus' last name. And she captured the imagination of a virginal nation.

Columbia's roots aren't as clearly traceable as those of Uncle Sam's, but early references predate Uncle Sam by over a century. In a now famous letter, a former slave named Phyllis Wheatley sent a poem to George Washington in the year leading up to the American Revolution. In the poem, the virtuous Columbia guides Washington to victory over the British. Washington responded to the young poet, praising her and inviting her for a visit should she ever be near headquarters.

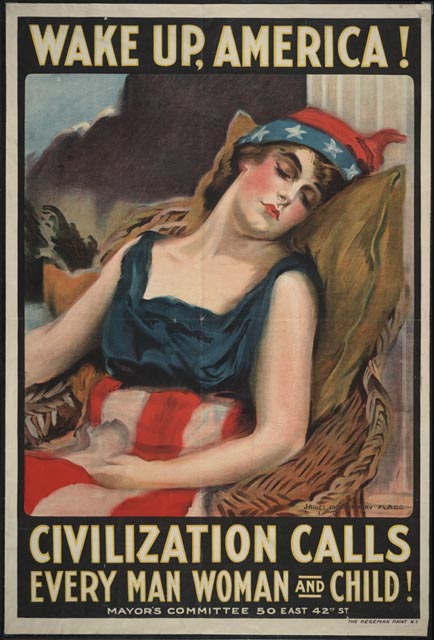

At the time Uncle Sam was just emerging, Columbia was already appearing in political cartoons. Depictions varied over time, but by the late eighteen-hundreds she was commonly found draped in the U.S. flag. By 1900, dressing as Columbia for Independence Day parades was all the rage. A San Francisco newspaper article went so far as to describe how a proper Columbia should look and act.

Columbia remained a prominent symbol of the United States through the end of the First World War, but then began to fade from view. One of the few enduring images can be found on the logo of film giant Columbia Pictures.

Experts differ on the reasons for Columbia's demise. Some argue that Americans became tired of her message — an often burdensome message of self-sacrifice. Others point to the ascendency of the Statue of Liberty as she worked her way into the public consciousness. Still others point to Columbia's femininity. While the pure young woman resonated with a flowering nation, she failed to connect with a country that increasingly viewed itself as a dominant world super power. Uncle Sam could wield a club. Columbia couldn't. Whatever the reason, few people today would identify Columbia as a national symbol of America.

And she's not alone. Britannia, Germania, and many others — all female personifications that fail to captivate with the same allure they once did. One important exception is Marianne of France, whose image remains tightly linked with French national identity. Statues. Engravings. Stamps. Coins. Her image even appears prominently in blue, white, and red on government issued documents, along with the words liberty, equality, and fraternity.

It's sad that Columbia's been lost to history. But who knows. Maybe she could return as Uncle Sam's spouse. Symbolically, they'd make a nice couple.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

French Symbols. From the France This Way Web site: http://www.francethisway.com/info/france-symbols.php. Accessed November 27, 2011.

M. Pitz. Hail, Miss Columbia: Once a U.S. Symbol, She's Lost Out to Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty. The Pittsburgh Gazette, March 18, 2008.

D. McClarey. George Washington and Phyllis Wheatley. The American Catholic, April 6, 2010. See also: http://the-american-catholic.com/2010/04/06/george-washington-and-phillis-wheatley. Accessed November 27, 2011.

The pictures of Miss Columbia and Uncle Sam are in the public domain as the result of expired copyrights. The picture of the logo with Marianne is from a French government Website.

This episode was first aired on December 1, 2011