George Forbes

Today, a forgotten electrical pioneer. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

George Forbes was a Scottish scientist/engineer born in 1849 and educated at Cambridge. By age 23 Forbes was professor of natural philosophy at the University of Strathclyde, focusing on astronomy, electricity, and the speed of light.

He soon led an expedition to Hawaii to record the rare transit of Venus. Then he chose the oddest route back home — through China, the Gobi Desert, Siberia, and St. Petersburg. That adventure led to his serving as a correspondent during the Russo-Turkish war. His next move was an equally wild digression, but it was visionary.

He went to London to learn about electric power and light. Joseph Swan had just perfected an electric light (before Edison) and commercial electric motors were less than a decade old. Forbes was soon manager of the British Electric Light Company. He took a place on the ground floor of a technology poised to alter life as we knew it. He went on to help power development all over the world. He advised on the Niagara Falls hydroelectric power system.

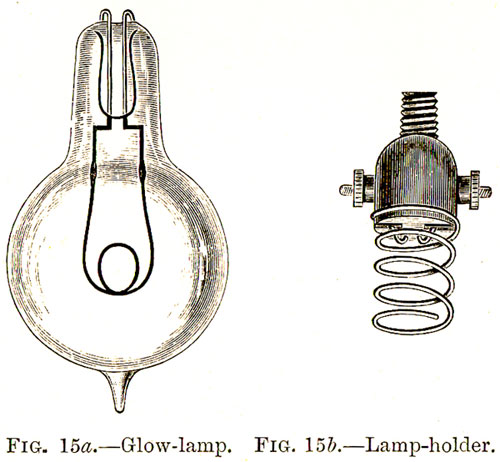

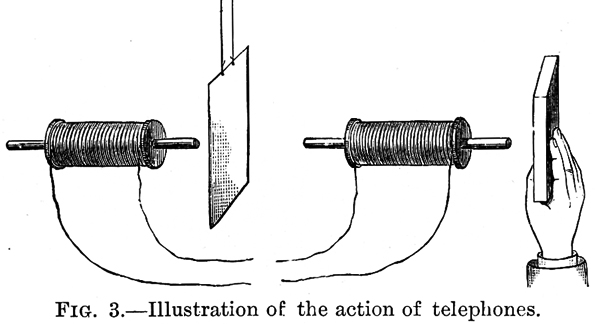

His accomplishments were vast; and he was well-known. Yet I learned his name only when I tripped across his 1888 book on Electricity. It's a set of lectures on electric principles, followed by a chapter on electric machinery. Despite Forbes' vast work on electric power and lighting, the telephone, telegraph, and light bulb appear only as illustrations of how electricity works.

Forbes' experiment showing how induced electromagnetism causes vibration in early telephone membranes

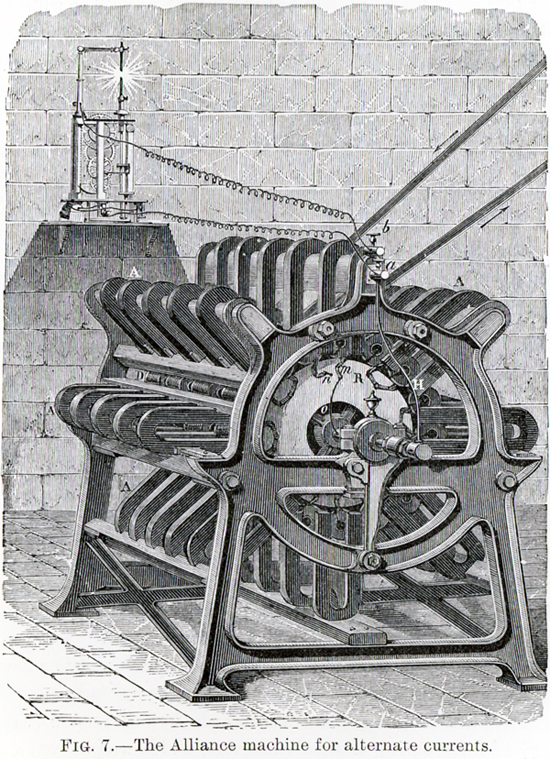

But that last chapter — almost an afterthought — on electric motors and generators holds an odd surprise. He begins with alternating current, then says, 'I now pass ... to the greatest improvement ... the continuous current machine.'

For Forbes, AC was more obvious and it preceded direct current. Edison had entrenched DC at the outset here in America. Westinghouse had to fight for AC. Our Niagara Falls power plant, influenced by Forbes, was one of our first AC plants.

So history flows from these old pages. And not quite the history we all know. Forbes' style is descriptive with wonderful steel-plate illustrations and no equations. He laid his stamp on the new 20th century. His work on gunnery and range-finding alone served Great Britain in both world wars.

Then, at 57, another odd move: Forbes, who'd never married, retired to Pitlochry village in Scotland. He withdrew from people to write. For a while, his books on astronomy and electricity, articles with still-new ideas, continued their influence.

The Alliance AC generator was an early power source

for French and English lighthouses

And yet, at length, the world forgot him; and his fortunes dried up. When he died at 87, I was a child in the first generation that would now live fully in his electrically-powered world. At the end, Forbes was puzzled to see himself lost to the public eye. Yet that was really a choice he'd made. Now I meet him in this old book, and he's someone we really should know. So let's hold onto the name of quiet George Forbes who gave us so much.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. Forbes, Course of Lectures on Electricity delivered before the Society of Arts. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1888). All illustrations on this page are from this source.

For more on Forbes, and for his picture, see also the articles in ElectricScotland.com and Wikipedia.

I fudged when I said that Forbes' first post was at the University of Strathclyde. It was then Anderson College and only later became the University of Strathclyde.

This episode was first aired on December 2, 2011