Houston Maritime Museum

Today, a tale of two museums. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Yesterday we discovered a new museum here in Houston. And to say what it was, I need first to say what it was not. To do that, I'll tell you about another museum I recently saw, in another city.

There, mobs of raucous school kids raced past artifacts along the way to each gathering point. Here they'd be briefly lectured and turned loose among the next group of push-button displays.

I dodged the hurtling bodies, trying to absorb a Model-T Ford -- the embryonic family car that reshaped America. No hope of letting it seep into my system where sense and meaning could merge. Here you poked buttons, made incomprehensible things happen, and gained only kinetic satisfaction in a world without meaning.

That was last month. Now, a radically different experience: Houston's Maritime Museum occupies a house in a quiet neighborhood. We expected something minimal and were amazed when the house opened into room upon room -- each offering new surprises.

To call it a display of top-quality, highly-detailed, model ships would be true, but misleading. These models, some eight feet long, are rendered in an astonishing wealth of detail and range of examples. They're also surrounded by every kind of historical artifact -- a whole case of items from and about the Titanic, a nineteenth-century diver's helmet, ancient anchors, and so much more.

You cannot race, unseeing, past these displays. The muted surroundings compel you to slow down and seek out meaning. You find yourself comparing forms of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century warships -- frigates, ships of the line, and corvettes. You begin to see the subtle changes in shipbuilding that shifted naval greatness from Great Britain to its upstart Colonies.

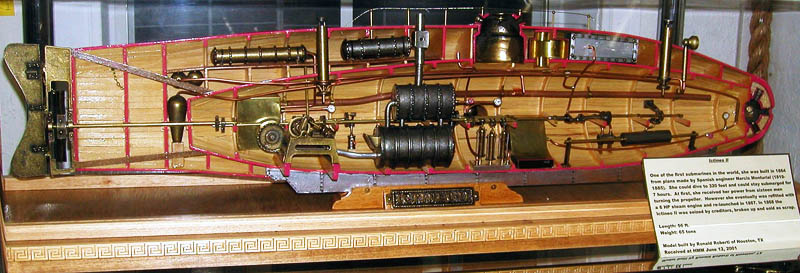

You're equally caught up in the history of oil tankers, oar-powered galleys, fishing ships, and commercial ocean travel. You also encounter things you'd never expect: Here's a Spanish-built hand-powered submarine, made in 1864 -- same year as the well-known Confederate submarine, Hunley, here in America. But the Spanish one is actually more sophisticated.

At the heart of all this is marine engineer James Manzolillo, the museum's founder and director. Manzalillo served with the Merchant Marine in WW-II. He survived torpedoes, and he went on to become a shipbuilder in Mexico.

There're few ports Manzolillo hasn't visited. Now he combines his collected artifacts with contributions. The result is more an act of love than a museum. What he's accomplished, and what that other museum did not accomplish, is to create a dimension of reverence.

For the past emits a presence. Move by it too quickly, fail to engage that presence, and the past will be no more than yesterday's junk. But this place slows you, and engages you. As I left Manzalillo's Maritime Museum, I could hear the creak of a wooden hull and smell the creosote. I could actually taste the salt air.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Houston Maritime Museum has since been moved and upgraded. Click here for its present website.

The SS United States. For its story, see Episode 421.

A WW-II Liberty Ship. For its story, see Episode 1525.

A Spanish Submarine built in 1864. To learn about the Confederate submarine built the same years, see Episode 381. For more about early submarines in general, click on the image above.

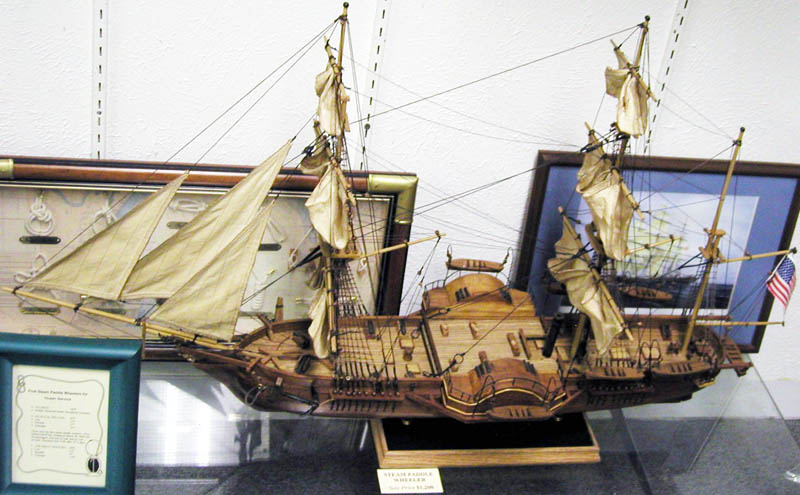

An early transatlantic steamboat. To learn about the first steam-powered Atlantic steamboats, see Episode 1338.

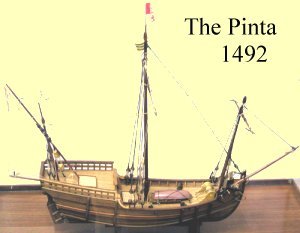

An early American-built frigate (1778). To learn how American frigate-building progressed after this, see Episode 1267.

The 104-gun HMS Victory, 1765, Lord Nelson's Flagship.

James Manzalillo in the Houston Maritime Museum.