The Last Masts

Today, we wonder about sails on steam-powered ships. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Robert Fulton's original steamboat was equipped with two sets of sails in 1807. River boats quickly abandoned sail because they always ran near a shore. Sail wasn't much use in the narrow confines of a river. But relinquishing sail at sea after using it for several millennia was a terrifying step to take. The American packet City of Savannah crossed the Atlantic under steam in 1819. It hadn't reached Ireland before it used up its coal and had to run up its sails. When Britain's steam-powered Great Western established regular transatlantic passenger service in 1837, it carried sail.

How long do you suppose it took to gain the confidence needed to give up expensive back-up sails, masts, rigging, and crew? Actually, the beginning of the end of sail was the battle between the Yankee Monitor and the Confederate Merrimac in 1862. Those steam-powered, ironclad ships didn't carry sail because they were meant to be shoreline vessels. Not everyone realizes they were only two in a great armada of ironclad riverboats. The Union made effective use of them in the Civil War. Ironclad gunboats helped the Union Army to gain control of the Mississippi River in the west.

But the Monitor had one entirely new feature destined to change the game entirely: In its center, where a mast might have been, there was instead a gun turret. At this very same time, the conservative British Admiralty was also trying to replace the fixed guns on their ironclad warships with rotating turrets. Their problem was that masts and rigging interfered with the field of fire of a turret. The flat, sailess Monitor had no such problem.

Yet the British clung to sail. They built several ships with both turrets and masts. All the while, that arrangement gave them trouble. Not until 1871, 64 years after Fulton, did the British Navy launch the first ocean-going warship without any sail -- the H.M.S. Devastation. The Devastation set the pattern for future British sea power, but masts were still to be found on many merchant and passenger ships well into the 1900s, a full century after the first ocean-going steamboats.

Since sails offer power without fuel, we must ask whether the issue was conservation of fuel or conservatism of mind. Naval architects today talk about adding modern forms of sail on merchant vessels. But though 19th-century engineers were many things, they were never conservationists. The long retention of sail represents an extreme instance of conservatism in engineering.

That conservatism becomes understandable when we consider how much more than mere technology sails were. When steam first came on the scene, sail was woven through our language and our thinking. Even today, the words linger in our speech: "That really took the wind out of her sails." "He was three sheets to the wind." "May the wind be ever at your back!" Leaving sails behind was far more than a simple changeover in the way we powered ships.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This is a revised and expanded version of Episode 31.

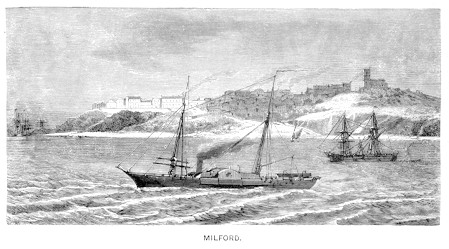

A Steam-driven, sail-assisted, ship on the south coast of England not long before 1883 (76 years after Fulton's boat).

From Picturesque European Scenery, Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1883

A Frigate Powered by both Steam and Sail from Man on the Ocean, 1874

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Isambard Brunel's Great Eastern from Man on the Ocean, 1874

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library