The Socotra Archipelago

Today, the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

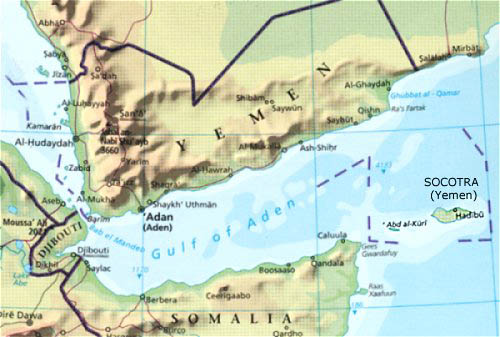

The Socotra Archipelago reaches 250 miles east from Somalia into the Indian Ocean. Its four islands lie about that same distance south of Yemen. The area of the large island, Socotra, is 1400 square miles. Quiet and remote, its population is some 44,000. (Only sixty or so people live on the three small islands.)

For years the Archipelago was owned by South Yemen, a Marxist friend of the old Soviet Union. A Soviet air base on Socotra kept it isolated. Then, the Soviet Union collapsed, North and South Yemen reunited, and the Archipelago began opening up. In 1999, passenger jets began flying in. Now developers want to start building five-star hotels and golf courses.

But there's a catch. Socotra is a great pocket of odd flora and fauna -- like the Galapagos. Both are small chains, severed from the historical flow of evolution in the continents. Both are homes to major, separate, evolutionary processes.

More than eight hundred plant species have been identified on Socotra, and 240 of them are unique. The study of its animal species is far less complete. So far, 140 bird species have been identified, with new ones turning up all the time. Socotra's reptiles are almost all indigenous species.

The identification of Socotran insects has hardly begun. But one general feature is apparent: The indigenous ones all have shorter wings -- wings that keep them from reaching the mainland.

For all this biodiversity, Socotra has no indigenous mammals beyond some local bats. That, and the kinship of its plants with ancient forms, suggests that Socotra has been isolated from Africa and the Arabian Peninsula since before the evolution of mammals.

So this is a fine window into the past. Science Magazine goes to Yemen's minister of foreign affairs, Abdulkarim Al-Eryani, who happens to be a Yale-educated biologist. Al-Eryani points to some imported sheep, munching quietly upon a very unfamiliar-looking tree. As they chew, a red fluid flows forth. This is called the Dragon's Blood Tree, for it bleeds red sap when it's wounded.

The United Nations has now pledged five million dollars to explore sustainable development and conservation on Socotra. Yemen has put in another third of a million. And, while they work on protecting Socotra, you can book an ecotour. But you'll find no hotels on Orbitz -- well, at least not yet.

The people of Socotra fish, herd, and do subsistence farming. The fishing's superb, and, in recent years, Socotran waters have drawn outside fishermen. Their large boats and net-fishing pose a severe threat to the Socotran food supply.

Well that's the problem when you live in Eden. Others want to join you -- with their five-star hotels, golf courses, and dune buggies. I write this in 2004 and I will certainly want to take another look at Socotra in -- say -- 2010.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This web site offers photos of flora and fauna on Socotra (including the Dragon's Blood Tree) as well as advertising an ecotour: http://www.viewzone.com/yemen/socotra.html

E. Sohlman, A Bid to Save the 'Galapagos of the Indian Ocean'. Science, Vol. 303, Issue 5665, 19 March, 2004, pg. 1753.

The island of Socotra is identified on the right. You can make out one more island member of the Socotra Archipelago to the left of Socotra.