Inventing Modern: And Creating An Unexpected Future

For the World Future Society Annual Conference, Westin Galleria Hotel, Houston, Texas

Plenary Session, 7:00 PM, Sunday, July 23, 2000

by John H. Lienhard

Mechanical Engineering Department

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-4792

jhl [at] uh.edu (jhl[at]uh[dot]edu)

We're here because we all have a profound interest in mechanisms by which the future spins out of the past. And, of course, we must inevitably look at history to see the future. So this evening let's look at one epoch of profound change — and at a future no one got right. I'll begin at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, America's third world's fair. It'd been four centuries since Columbus's voyage. We were young, strong, at peace, and feeling our oats. England began the cycle of world's fairs with the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851. Other countries, America included, followed. By 1889 the Paris exhibition, with its Eiffel Tower, had attracted 32 million people. World fairs had become a very big deal.

Now it was our turn to create a "fair to end all fairs." Congress backed the idea, and American cities vied for the honor. In 1890 Chicago was anointed as the city with the best rail access, the most space, and the will to do the job. So we set out to create "a midwestern Venice" on a swampy six-hundred-acre tract by Lake Michigan.

In today's dollars, the budget was around half a billion. Add to that what was spent by 65,000 private, national, and international exhibitors, and it was a vast enterprise. The original Ferris wheel, whose size has yet to be matched, rose alongside it.

Yet old photos show nothing of the coming century. The architecture is that of imperial Europe. The electrical hall is filled with telegraphs and telephones, electric railways, elevators, and lighting. But there's no hint of radio, and no one sees that small electric motors will soon transform both the home and workplace.

The transportation building holds bicycles, railways, and steamships, but no automobiles. The most popular exhibit is a display of farm windmills. The fair summarizes our condition in 1893 and reveals almost nothing of any future.

The one accurate glimpse of the coming twentieth century was accidental. The women's building was designed by 21-year-old MIT graduate Sophie Hayden. It was meant to showcase the women's clubs of America, but it was filled with women's accomplishments in science, health care, literature, invention, and art. Quite unexpectedly, it emerged as the very heart of the now-unstoppable suffrage movement.

The fair drew 21 million people. By displaying the diverse forces that'd made us, it did draw us together and shape a national identity. It reminded us of what we wanted to be. No wonder poet Katherine Lee Bates went home to write America the Beautiful after she'd seen the fair. But the famous phrase, Thine alabaster cities gleam, described the pavilions of the fair far more accurately than they described any American city!

So we entered the twentieth century with no clue to the so-called Modern world that awaited us. Now you and I advertise the fact that we don't know where we are by calling our times post-modern.

There was no such doubt by 1930. I was born into the world that knew it was modern. Modern was on everyone's lips. For me, it's strange to hear people speak of it as a time gone by. Back in the 1930s, we knew something immense had happened to us. But what, exactly, had happened?

The other day it struck me when I chanced to notice that a great scientist I was writing about was born the same year as Einstein — 1879. On a hunch I went off to check other people born around that date. Niels Bohr was born just six years after Einstein, and Schrödinger four years before.

These people had redirected human thinking in remarkable ways. So I looked further. Picasso was born two years after Einstein; James Joyce three years after; Schönberg four years before. The Wright Brothers were only a decade older.

Now it's perfectly obvious that the great minds at any date will've been born around the same time. Nothing interesting there. But I wondered about the world that'd made this particular set of people. What had that world said to them when they were young? How had it sent them off to wreak such radical change?

I suspect that what it showed them was frustration. The problems of science had been yielding, right and left, to new instruments, math, and physical theory. Only a few nagging problems lingered: The inexplicably constant velocity of light teased us. Classical physics had failed to predict how the energy of light and heat varies with wavelength.

The art of that classical world was Salon Art: extraordinarily realistic images of larger-than-life romantic unreality. Like physics, art had nowhere to go. Nor did the rich, overblown music of the late Romantics. How were you supposed to take it further? Transportation had run to the end of its tether. At a hundred miles an hour, railroad trains could go no faster. The vaunted Clipper Ship had topped out at fourteen knots.

It was a world filled with vast accomplishments. But it was also a world of technological ceilings, social ceilings, and scientific ceilings. Just when our revolutionaries were young adults, beginning to make a mark, Henry Adams wrote something very telling — something I think any futurist should take to heart.

Adams was visiting the next great world's fair, the 1900 Paris exhibition. He looked at all that machinery and said, in effect, that the great blind spot at the end of the nineteenth century was our denial of mystery.

Sure enough, the geniuses born in the 1870s and '80s were the ones who'd find mystery once again. For we'd tried to leave it behind in a rational, deterministic world. But mystery is the one thing we cannot do without.

Einstein gave us the mysterious neverland of relativity. Schrödinger reduced the contradictions of quantum physics to that single mysterious hypothesis we call the Schrödinger equation. Picasso offered a vision of reality just as disorienting as relativity or quantum uncertainty. Schönberg declared freedom from the tonal hierarchies that'd bound music for five hundred years. James Joyce made mincemeat of prose as we'd expected it to sound.

And the only futurist to see it coming was the medieval historian Henry Adams. No one else pinpointed anything so subtle within the materialistic ferment of the 1890s. No one else was keyed to see the mysterious reach of human need.

We'd been getting all kinds of false signals by 1900. During the late nineteenth century we churned through new technologies, all harbingers of the big changes ahead. The period was filled with short-lived, flash-in-the-pan technologies.

The Pony Express went into service in April 1860 and served for only seventeen months. Riders covered over 1800 miles from St. Joseph to Sacramento in ten days. All that action-based derring-do was soon to be overtaken by the telegraph. The Clipper Ship was the Pony Express of the high seas. In 1843 Chinese teas emerged as lucrative trade goods. Huge profits could be turned by getting tea to New York quickly. The Clipper Ship was a new kind of vessel. It was fast, but it hauled only a light cargo. For twelve years Clipper Ships coined money. Then the tea boom ended, and so did an epoch of marine history.

And who's ever visited San Francisco without, at least once, riding her famed cable cars? In 1873 San Francisco replaced horses as the power source for her public buses with a long, continuously-moving, steam-engine-driven, cable. Other cities copied her cable cars. But, just a decade later, we had public electric systems. By 1890 electric trolleys had wiped out cable cars. The San Francisco system lingers only as an icon.

Cross-country cattle drives are another American icon. But such a rudimentary technology of getting meat to packinghouses couldn't last. After ten years, railroads and cattle cars arrived to serve the newly settled West. And big cattle drives were no more.

Of course these were all straightforward attempts to bring in a future. But we had to learn that the future we now faced could only ride in on the back of mystery.

Nowhere did the intensity and subtlety of revolution turn upon us with more force than it did in the visual arts. The art world was in ferment by 1913. That year, a group of New York artists created one of the largest art shows ever mounted — and one of the most important. It'd all begun when sixteen young artists formed the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, the AAPS. The powerful National Academy of Design, dictator of American tastes, figured that if they ignored the revolution, it'd just go away. The AAPS meant to change that. Its first order of business was to exhibit the new art — to show the world where art was headed.

But where might they put it? Madison Square Garden cost too much. Everything else was too small. Then one member said, "Let's rent an armory." That was a stroke of both genius and irony. For half a century, big American cities had built wild, fanciful armories in the style of medieval castles. We were afraid of the Union Movement. We built those architectural dinosaurs to control unrest among the workers.

So the AAPS rented a menacing old armory with its huge floor space. Into that space went the art of van Gogh, Braque, Cassatt, Seurat, Munch, Matisse, Hooper, Picasso, Bellows. Rank on rank, the great art of the age poured in from Europe and America.

The exhibit opened to four thousand people. The papers made news of it any way they could. They ridiculed the art, but no matter. The public had seen it, and they understood. Just as the exhibit closed, twelve hundred striking workers marched into New York from Paterson, New Jersey. They'd been organized by the same intelligentsia who'd backed the show. The revolutionary connection was quite explicit.

There was no shaking off a new vision of the human condition. Georgia O'Keeffe went back to reinvent her art. Duchamp's cinematic cubist painting of a Nude Descending a Staircase was the star of the show. A buyer got it for $324.

The AAPS didn't survive the exhibit, but it didn't have to. The intensity of this gathering — the counterpoint — revolution housed in that counter-revolutionary armory! It gave us new eyes. The art changed us in ways we're still trying to understand a century later.

Stirred in with all the abstraction of modern art was a new functionalism. Art and technology had become mirrors reflecting one another. Think about the late nineteenth-century arts and crafts movement or the German Bauhaus school. Art and technology had become one. Architecture, in particular, fairly screamed the new themes of Modernity at us. Art deco, with its vertical lines, was the hallmark. But those vertical lines reflected a new verticality — or should I say vertigo — in our buildings.

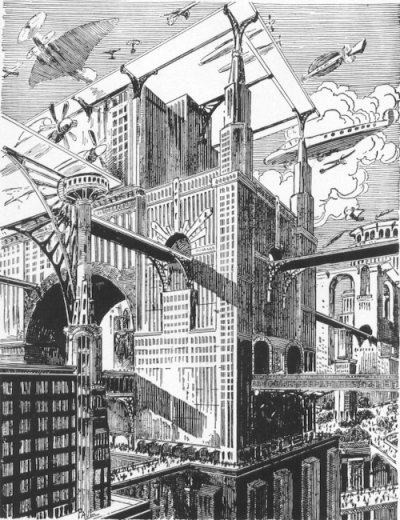

The skyscraper was the new architectural focal point. Electric elevators came in during the 1880s. They offered efficient means for moving people up and down. Now buildings sprouted upward like Kansas sunflowers. And, for a season, we wanted them to rise even higher. As cities raced skyward, our vision of the modern city raced even faster. Just thirty years after the electric elevator, tall buildings had given birth to a radical new concept of human dwelling.

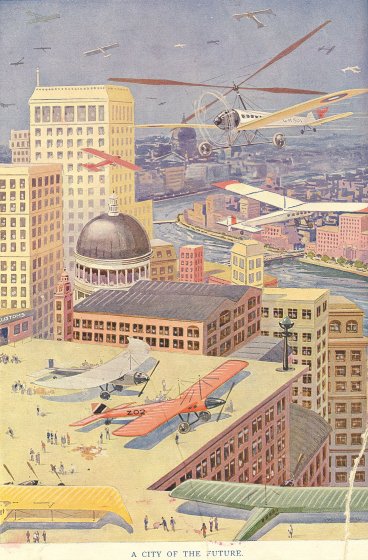

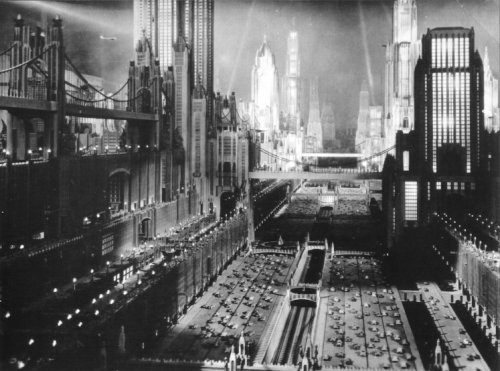

Fritz Lang's movie Metropolis captured the new vision in 1926. In our generation, movies have rediscovered it. But they add sinister overtones. Blade Runner andBatman show the 1920s city gone mad. The image is powerful. Buildings rise, layer upon layer. Multi-tiered highways flow among them on many levels. Higher up are airways. Airplanes and helicopters move through the upper levels of skyscrapers.

And it all goes up, up, up. Is there a bottom to the picture? Who knows! The bottom's out of sight. All we see is up. The vision is Gothic — right down to the gargoyles and ornate towers. Only the flying buttresses are replaced by upper ribbons of highways.

Wanamaker's department store assembled this vision in October, 1925. They put on an art exhibition called The Titan City, a Pictorial Prophesy of New York, 1926-2026. And there was that Gothic reach of the city into the sky. It goes up, up, up — in painting after painting.

Rockefeller Center was the spawn of that idea. Its architect was one of its theorists. Yet that vision was not to be. Oh, you catch a sense of it today in, say, lower Wall Street. You see a bit of it when the evening sun flares on the steel and glass of downtown Houston. But, in the end, we'd extrapolated the present too far. We'd failed to catch the mysteries of the human heart or the impact of parallel technology. For we now had the automobile. Our parents chose not to centralize and build upward. They chose instead to build outward. After World War II, we moved to the suburbs, and we live in outlying neighborhoods if we can. We flee the technocracy of high concentration.

Now and then we grasp at a Faustian vision of technology for technology's sake. Or we're carried away by some Tower-of-Babel impulse. But the things we build are ultimately creatures of our hearts as well as our heads. In the end, we build to the grain of our own human nature.

Outwardly, the automobile had been the wild card that destroyed predictions this time. Just as we were converging like planets into a black hole of centralization, the automobile caught hold of us and flung us all outward. But the thread of mystery (or, at the very least, surprise) lurks within the influence of the automobile as well. Consider one architectural movement that arrived before you were born and which has now blown away like summer smoke.

I refer to a new architecture of instant communication. In the brave new world of 1930, cars whizzed across America on two-lane concrete highways. We were linked together as we'd never been. Before we realized it, cars had become not just a twentieth-century medium of communication but a metaphor for communication as well.

We began talking to our cars. Burma Shave signs hailed them as they passed. For a thousand miles either side of Wall's South Dakota drug store, signs told of that kitsch oasis on the road ahead. We began doing what medieval businesses once did. You didn't find a tavern's name, "Head of the Horse," written over the door. Too few people could read. Instead, you saw the carved head of the horse itself.

California rediscovered that childlike directness. First, the state declared its architectural independence with Spanish Colonial adobe and stucco. Next it moved on to exotic themes — Grauman's Chinese Theater and the Aztec Hotel, all the splendor of the silent movies.

Then California, and America as well, moved all the way to Wonderland. You found yourself buying lemonade from a building shaped like a lemon — or ice cream from an igloo, film from a shop shaped like a camera. You entered a huge coffee pot to drink coffee. Buildings also took forms without rhyme or reason — diners shaped like boxing gloves, zeppelins, dogs, and pumpkins. Pure means for catching a driver's eye. Architecture was supposed to be more subtle. But there's little time for subtlety at sixty miles an hour. A Los Angeles Coca-Cola company was shaped like an ocean liner. Sometimes form followed function as doggedly as your shadow follows you. Sometimes function was as irrelevant as a dream.

This was not just cuteness. It was a way to make the break and begin again. The new cars told us we had to reorder our lives. We answered our cars in the language of architecture.

And so this modern age that I've been describing rode right through the major catastrophes of the early twentieth century — World War I, the flu epidemic, World War II. Catastrophe has always been external to the rhythms of human creativity. Creativity and invention, those great destroyers of predictions, have always come from some place in the human heart that remains protected from mere exigency.

During the Great Depression, for example, we all fed the stranger at the door. We picked up hitchhikers. We shared what we had. We created the PWA and then the WPA. And through them, we kept right on building our modern world. We erected art deco buildings and decorated them with murals of workers. And those workers went right on building our great vertical cities.

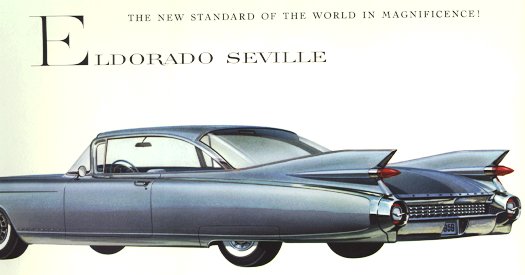

But, by the end of World War II, the modern age began winding down — though we didn't realize it right away. It'd been a sweet time in human history, despite the evils that'd swirled through it. And, in 1950, we still believed that the world was our oyster. We would stay modern for a few more years. Our 1950s cars with their great vertical tail fins were, in fact, some of the finest machines in the world at that time.

But 1950 makes a good place to finish. Let's look at an article published that year by the New York Times science editor. He describes for us a fictitious Ohio town in the year 2000. The town center is an airport. Triple-decker highways radiate outward from it — express traffic on top, local traffic in the center, business vehicles below. The cars burn alcohol.

The family helicopter pad is on top of the garage. To leave town, you can fly by rocket or jet plane. Supersonic rocket trips are expensive, so most of us use jets. Ocean liners are still in use, but now they use atomic power. Transportation is a huge fixation.

The second great theme in the article is the home. Men shave with chemical crèmes. To clean your living room you simply take a hose to it — everything's waterproof. Dishes are disposable. Microwave ovens have replaced conventional ones, and you buy most food precooked. Many foods are made synthetically from sawdust.

The new TVs are now in everyone's home, and they double as video telephones. The author sees solar and atomic power in competition. He recognizes the importance of the new antibiotics in medicine, but he fails to see germs evolving to protect themselves. He does correctly guess that cancer will still be around.

Why was a well-informed author wrong on so many points? Why do technological predictions almost always go wrong? Well, on one level, he correctly identified many of the wants we craved to have fulfilled. But he was far off base in seeing how invention would ultimately fulfill them.

One prediction in this article hints at the larger problem. The author sees only one use for the new computers. They'll give accurate predictions of the weather by solving the equations for the movement of air. Ten years later, meteorologist Edward Lorenz tried just that. When he failed, he realized it was because he could never specify the initial weather accurately enough. All future predictions depend absolutely on miniscule differences in our descriptions of the present instant. If I so much as choose to eat pasta instead of stew at lunch, I literally alter human history.

Who, in 1950, could know that Jack Kilby would create a primitive integrated circuit eight years later, or that only three years later the discovery of DNA would overturn both medicine and human self-perception? Xerox machines were just about to reach the marketplace in 1950. Try diagnosing their impact!

Predictions are extrapolations that cannot take account of inventive intervention. Invention that doesn't send us off in new directions is no invention at all. If we could predict the future, it'd be because we lived without the wonderful wildcard of human creativity. And that'd be a terrible thing.

But your business is not predicting the future. Rather, it's showing us how to livewith, and into, the many complex futures that might lie before us. And, if there's one thing I'd like to stress this evening, it is that the future truly lies somewhere off in the mysterious reaches of our psyches.

We all want to create reasonable scenarios for the future. So look back at the brief bright epoch of Modern America — at that wonderful age that belied all the horrors swirling outside the window. I think the clues are there. Those who were most wrong about the future all had their feet firmly grounded in the obvious realities of the present. Those who most nearly got it right followed metaphor. They followed the human heart. They followed far subtler hints than our obvious needs and our obvious wants.

Image of the Modern City from the set of the 1930 musical, Just Imagine.

Image from a 1928 issue of Amazing Stories.

SOME SOURCES

Bolotin, N., and Laing, C., The Chicago World's Fair of 1893: The World's Columbian Exposition. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1992.

Adams, H., The Education of Henry Adams, Vol. II. New York: Time, Inc. Book Division., 1964, Chapter 25.

For more on the early history of quantum mechanics, see Tien, C. L., and Lienhard, J. H., Statistical Thermodynamics, revised edition. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corp., 1979. See especially Chapter 4.

Snow, R.F., Gravity's Rainbow. American Heritage of Invention and Technology,Vol. 5, No. 2, p. 5.

Brown, M. W., The Story of the Armory Show. New York: The Hirshhorn Foundation, 1963.

Green, M., New York 1993: The Armory Show and the Paterson Strike Pageant. New York: Collier Books, 1988.

Fogelson, R.M., America's Armories: Architecture, Society, and Public Order. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Willis, C., The Titan City. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Vol. 2, No. 2, Fall 1986, pp. 44-49.

Heimann, J., and Georges, R., California Crazy: Roadside Vernacular Architecture.Tokyo: Dai Nippon, 1985.

Margolies, J., The End of the Road. New York: Viking Press, 1977.

Liebs, C.H., Main Street to Miracle Mile: American Roadside Architecture. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1985.

Venturi, R., Brown, D.S., and Izenour, S., Learning from Las Vegas. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1972.

Short, C.W., and Stanley-Brown, R., Public Buildings: A Survey of Architecture of Projects Constructed by Federal and Other Governmental Bodies Between the Years 1933 and 1939 with the Assistance of the Public Works Administration. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1939.

Kaempffert, W., Miracles You'll See in the Next Fifty Years. Popular Mechanics, February 1950, pp. 113-118, 364, 266, 270, 272.