Skyscrapers

Today, let's talk about skyscrapers. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Skyscraper is such a fine evocative word! When I was a child, the 41-story First National Bank Building loomed larger than anything else in St. Paul, Minnesota. It really did scrape the very sky. Modern skyscrapers came into their own in the early 1890s. But, for that to happen, so many new technologies had to converge.

Before architects could take the bold step of raising buildings beyond about five stories, someone had to develop a workable elevator. Someone else had to recognize that the shell of the building should be hung on a steel skeleton — that it was not enough to hang iron facades on wood or brick frames. A whole new technology of building foundations had to be invented. Buildings now had to be designed to withstand formidable wind loads that'd hadn't occurred to architects of an earlier age.

The skyscraper was the phoenix that rose from the ashes of the great 1871 Chicago Fire. Before the fire, Chicago's architecture was uninhibited and undisciplined. The 18,000 buildings that perished were made of wood and brick, with some iron facing. The commerce that'd built Chicago was hardly hurt by the fire, and those commercial interests demanded that a new city be built, a fireproof city, an iron city. The other pressure was to make the best use of real estate in Chicago's crowded downtown area.

Two factions converged on the rubble: the freewheeling builders of old Chicago and a new breed of formal designers trained in analytical mechanics. Many of those new engineers were foreign, and they all reflected the influence of France's theoretical École Polytechnique. The two factions didn't agree, but out of their conflict emerged bold new concepts for making tall steel-framed buildings — concepts that had to be grounded on complex analysis.

These new buildings could not feasibly rise any higher than an elevator could carry its occupants. Hydraulic lifts had been around since the 1830s, but they couldn't go very high. Elisha Otis invented a safe steam-powered elevator in 1857, but someone had to keep stoking a fire under the boiler. Electric motors would have to be the answer, and the first electric elevators were tried out in Germany in 1880. Practical control systems finally made electric elevators effective in the early 1890s.

By the turn of the century, tall buildings were typically fifteen stories high. A scant thirty years later, the Empire State Building reached seven times that height.

And the great impetus for all this was Mrs. O'Leary's perhaps-apocryphal cow who kicked over a lantern and burned down a very real Chicago. That catastrophe led to a singular convergence of new technologies. And out of that mixing, the American city emerged as a completely new invention — a far more extraordinary phoenix than the half-formed city of old Chicago.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Peters, T. F., The Rise of the Skyscraper from the Ashes of Chicago. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Fall 1987, pp. 14-23.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 61.

For an interactive experience, visit The Skyscraper Museum.

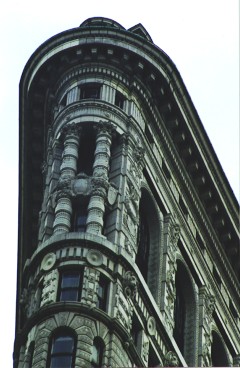

For more information on the Flatiron building, see: Flatiron Building.

Three steps in the completion of New York City's first skyscraper, the 285-foot-tall Flatiron Building, finished in 1902

(From the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Present day detail of the stone facing at the tip of the Flatiron building

(Photo by John Lienhard)