The "Color" Black

Today, black is the "color." The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run and the people whose ingenuity created them.

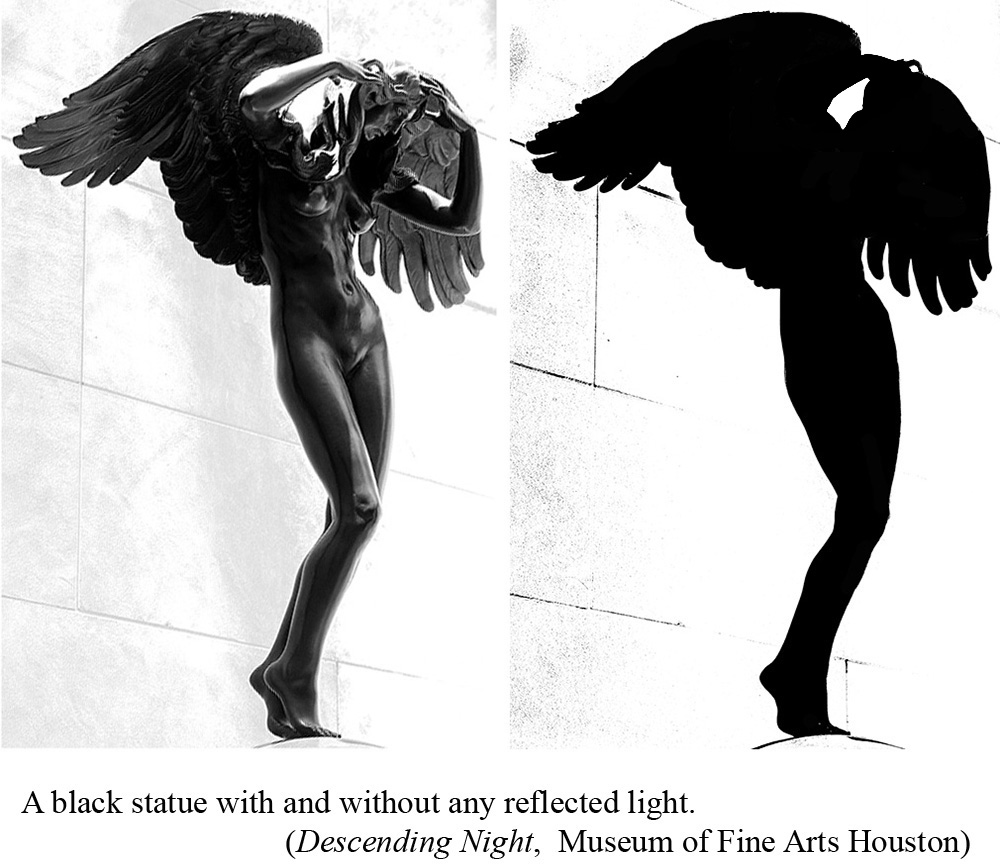

That song celebrates the color black. And we need to celebrate it further. But can we really call black, a color? The dictionary does. And we do get something close to black by mixing red, yellow, and blue paint. But we also get black by removing all color. The only true black is the absence of all light – of all color. The catch is: It's very hard to make any visible object appear completely black. It'll always reflect some light.

We need to create many things that appear black under normal light. Non-reflective surfaces around lenses, for example. And the less pure the black in a TV screen is, the more washed-out the picture looks. It's a major challenge to create vivid black electronically.

Or think about solar collectors: Things take on color by reflecting some of the light that reaches them. And heat from the sun is just radiation with wavelengths a bit longer than visible light. So we wish collectors could reflect nothing and absorb all incoming light and heat. We want the blackest surfaces possible.

So we need a standard of blackness to compare with the way real surfaces absorb or reflect radiant light and heat. How to create a pure black to compare with real surfaces? The only pure black object is a black hole – a gravitational well in space. No light can escape it. But we can't put a black hole in our laboratory.

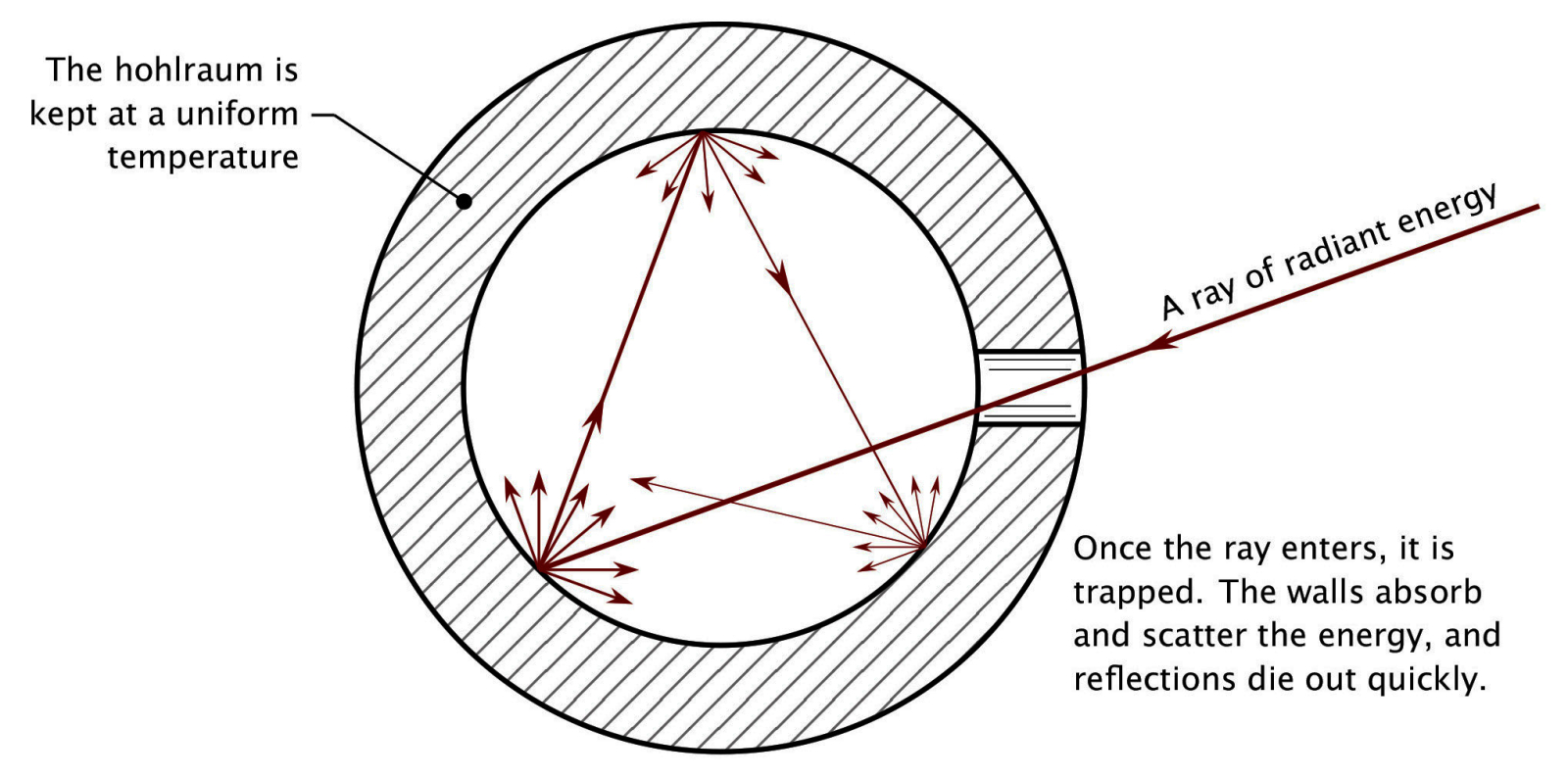

The classic standard of blackness is a large hollow sphere with one small hole. We make the inside as black as possible. Light or heat enters the hole and reaches the inner wall. A little bit reflects diffusely around the inside, and quickly damps out. Almost nothing radiates back out through the hole. So the hole is almost perfectly black. We call such a sphere by its German name: hohlraum, or hollow space.

Now a new technology is on the move: Forests of carbon nanotubes coat a surface and make it very black. One form, called Vantablack, is now on sale commercially. The latest at this writing in 2020 was a surface made by MIT engineers. It reflects only 0.005 percent of light.

A portion of this wrinkled metallic surface has been painted with Vantablack.

As a result, it appears as though it simply is not there.

It's disturbing to look at those almost-perfectly-black surfaces. We no longer see shapes or contours. It's as though part of reality were simply erased.

But pure black is a perfection we still can only reach for. Yet it's so desirable. We admire it in dark type on the printed page, in the beauty of ebony or obsidian, or in solar collectors. And when I think of blackness I hear echoes of that exquisite folk song, Black is the Color of my True Loves Hair:

(Once, more, Richard Dyer-Bennet sings a line from Black is the Color of My True Loves Hair.)

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For more about the black level in TV and monitor screens, see:

https://lcdtvbuyingguide.com/hdtv/black-level.html

or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_level

For more on light and heat radiation, see: J. H. Lienhard IV and J. H. Lienhard V”, A Heat Transfer Textbook, 5th ed., Dover Pubs. Inc., Mineola, NY, 2019. You can easily download the entire book, free of charge, at https://ahtt.mit.edu/ . Specifically, see:

Elementary ideas about heat and light radiation, hohlraums, and what surfaces do with incident light and heat, pgs. 27-31.

A more advanced treatment of radiation, Chapter 10.

Solar radiation, Section 10.6.

The recent history of carbon nanotube black surfaces is fragmentary at this point. But see: This early history from the National Institute of Standards in Boulder. CO. or the Wikipedia article on the black surface, Vantablack.

The MIT surface is the latest advance at this writing. See: http://news.mit.edu/2019/blackest-black-material-cnt-0913

The Wikipedia article on Black is very useful.

Richard Dyer-Bennet was a remarable singer and folklorist of the mid 20th century. For more on his work, see: http://richard.dyer-bennet.net/

The Vantablack image is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The hohlraum image is from A Heat Transfer Textbook. The Descending Night statue photo is by J. H. Lienhard.

I glossed over an often-asked question about solar cell collectors. “Why are they usually dark blue, not black?” The answer is that they're made of polycrystalline silicon. Monocrystalline silicon appears black but it's more costly. So we lose just a little efficiency by making solar cells affordable. Also, the cells are covered with an anti-reflecting coating. It helps to absorb most incoming light and heat; but still reflects just a bit of blue light.

This episode was first aired on January 13, 2020