Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection

by Chris Miller

Today, a bone collection. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A new body has just arrived. Two doctors and their protégés carefully move it to a table. They look over the body closely, noting its age, race, physical defects, signs of disease and likely cause of death. They record over 70 body measurements using high-precision instruments. A thorough dissection follows. Then the team removes all 206 bones from the body and labels each one with a specimen ID number. They stow the set of bones in its own Army-surplus ammo box for further inspection.

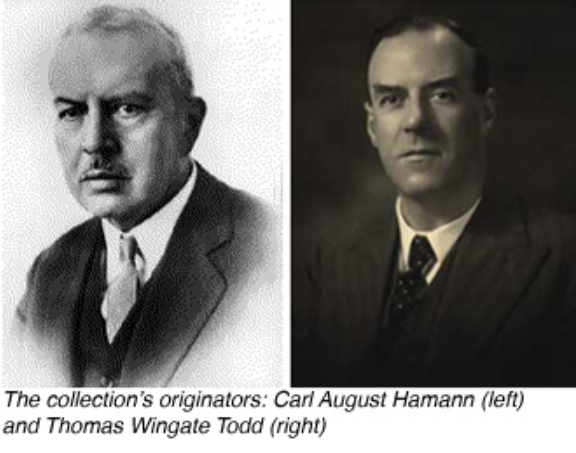

Is this some morbid scene from a horror movie? Hardly. I just described the arrival of a new specimen for the Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection. The two doctors were Carl Hamann and T. Wingate Todd.

Carl Hamann and T. Wingate Todd

Photo Credit: Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Carl Hamann came to the Western Reserve Medical School in Cleveland, Ohio in 1893. He wanted to create a teaching museum for anatomy there, so he began collecting human and non-human skeletons. He had gathered 100 full human skeletons when the school promoted him to Dean. No longer able to commit his time to teaching and the collection, Hamann hired T. Wingate Todd to continue the work.

Todd had prior experience cataloging specimens and a commanding, executive style. This fit perfectly with developing Hamann's collection. Todd, however, expanded the use of the skeletons from mere teaching tools to subjects for research. He studied the normal growth of bones and the effects of disease. Todd only drew conservative conclusions. He never speculated beyond what the data clearly showed. Yet he wasn't afraid to challenge the work of his colleagues. He disproved untested, but long-held, beliefs that littered the field of anthropology at the time. For instance, he debunked the myth that the skulls of African Americans had smaller brain cases than Caucasians.

Human ribs and spine with idiopathic scoliosis

Photo Credit: Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Hamann and Todd worked with local coroners to obtain unclaimed bodies from hospitals, morgues and workhouses. Understandably, critics of the collection contend that it's incomplete, because it doesn't reflect the full diversity of Cleveland's population at the time. Most of the 3000 skeletons came from the indigent or low-income city dwellers, who tend to have higher rates of disease and illness. But this alleged weakness is actually a strength of the collection. With it, we can study the effects of many diseases and trauma on bone, while accounting for factors such as age, sex and body weight.

Medicine in the early 20th century saw the birth of new hi-tech devices, such as the X-ray machine. Each one aimed at finding "the lesion within." But this new precision came with a price. Doctors began focusing their diagnoses on smaller areas, thus losing sight of the rest of the body. Conversely, Hamann and Todd only used new devices to enhance their classic methods of dissection and observation. They kept their view of the body as a larger, unified whole, only narrowing their focus when needed. They understood that every body wants to share its story, especially when we get down to bare bones.

I'm Chris Miller, along with the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection is housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, but it is closed to the public. Only serious researchers with serious proposals may gain access to the Collection. Between 200-250 research teams study the Collection each year. It also includes 900 non-human primate skeletons.

You can learn more about the Hamann-Todd Osteological Collection from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Oberlin College Library, Cleveland Clinic, Wikipedia, and the Massachusetts General Hospital Magazine.

Medical education became more standardized and rigorous in the early 20th century. Carl A. Hamann is credited with transforming the Western Reserve Medical School into a world class medical center.

Kevin F. Kern (University of Akron) wrote an excellent and thorough biography of T. Wingate Todd.

Hamann and Todd started a machine shop at the medical school to develop more precise instruments for measuring the body. One such device, the Western Reserve Craniometer, is still in use today. A craniometer measures dimensions of the skull.

To be complete in my explanation, Hamann and Todd stored each specimen's long bones (arms, legs), flat bones (pelvis, shoulder blades) and "others" (vertebrae, hand/foot bones) in the Army surplus ammo boxes. They stored the skull and delicate inner ear bones in a separate paper-padded box.

Todd not only believed in racial equality, but also gender equality. Todd mentored many female anthropology students and promoted their careers.

Todd was very skilled at clinical diagnosis. He could recognize previous maladies in a stranger just by looking at them.

Hamann died in 1930, and Todd died in 1938.

Collections similar to the Hamann-Todd Collection include the Robert J. Terry Collection at the Smithsonian Institution and the William Montague Cobb Collection at Howard University.

This episode was first aired on January 7, 2020