The World Wide Web

by Andy Boyd

Today, we browse. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The early 1990s were an exciting time for computer scientists as they witnessed the growth of what amounted to a shiny new toy: the internet. It was a giant erector set; an ever-expanding collection of computers linked together and ready to talk. But by itself, the internet was nothing more than an electronic delivery service. It was good at getting packages from here to there, but it had no interest in their contents. That left the door open for creative minds to experiment with what to put inside those packages.

Erector ad Photo Credit: Flickr

One pretty obvious idea was text; for example, research papers. But sending text alone wasn't enough. Pages of text have alts and paragraphs and all manner of formatting information. To reconstruct a page required instructions. And in 1989, while working at the European research agency CERN, Tim Berners-Lee devised the Hypertext Markup Language for just that purpose. It seemed like a good start, though other alternatives were being floated at the time. Still, Berners-Lee had high hopes for his creation. He went so far as to propose a name for computers that would share information using his newly defined packages: the World Wide Web.

HTML logo Photo Credit: Wikimedia

But there was another important step needed for the web to come to life. Berners-Lee's packages only contained instructions for making a readable page. To read a page, something was needed to take those instructions and reconstruct the page. That something was a web browser.

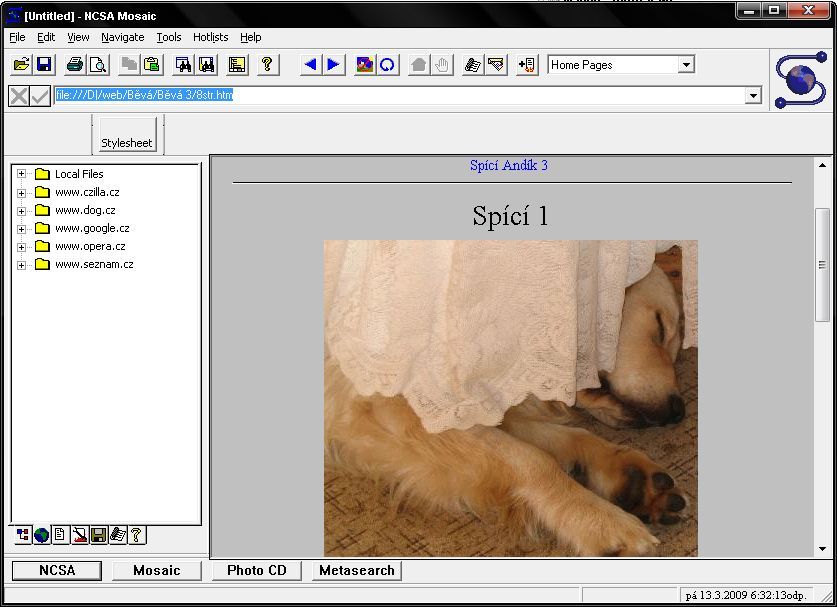

For Berners-Lee's World Wide Web to gain acceptance a good web browser was needed. Nothing really caught on until congress passed the High Performance Computing Act of 1991, also known as the Gore Bill after Senator Al Gore. Funding from the act made its way to the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois where two young computer scientists - one who was only an undergraduate - developed the browser Mosaic. Mosaic proved an overwhelming success, in part because it incorporated images instead of just text, and in part because it worked with Microsoft Windows instead of the systems typically found in university settings. In short, Mosaic made the web sexy, and it brought the web out of research labs and into the home. And talk about sexy. Music. Movies. Shopping. Email. Social Networking. We may or may not like it, but there's no arguing its ability to draw us into its, well, web.

Mosaic Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Working in a university environment, I've had the good fortune to witness advances in the web first hand. They all seemed quite incremental at the time, though looking back I'm as shocked as anyone to see how web use has exploded. And while so much has been driven by the private sector, it's interesting to realize that the web and the internet that supports it found their genesis in academic research settings.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The two computer scientists at the University of Illinois whose work on Mosaic was essential for growth of the World Wide Web were Marc Andreeson and Eric Bina.

HTML. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HTML. Accessed September 23, 2017.

Mosaic (web browser). From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaic_(web_browser). Accessed September 23, 2017.