The Last Masts

Today, we wonder about the use of sail on powered ships. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

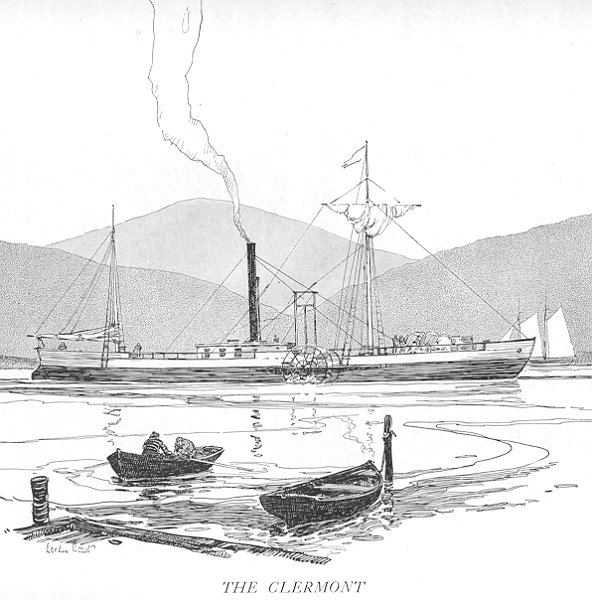

Robert Fulton's original steamboat was equipped with two sails in 1807. American riverboats quickly abandoned sail because they always ran near a shore, and because sail wasn't much use without a lot of room for navigation. But abandoning sail at sea, after using it for several millennia, did more than just violate tradition -- it was a very frightening step to take.

Robert Fulton's original steamboat was equipped with two sails in 1807. American riverboats quickly abandoned sail because they always ran near a shore, and because sail wasn't much use without a lot of room for navigation. But abandoning sail at sea, after using it for several millennia, did more than just violate tradition -- it was a very frightening step to take.

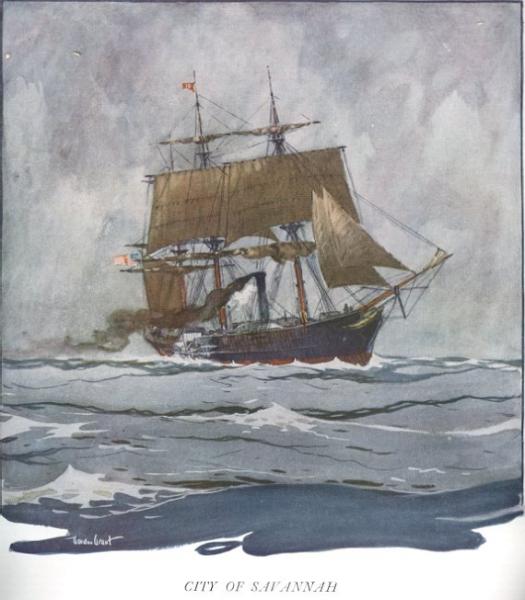

The American packet Savannah made the first transatlantic steamboat trip in 1819 -- at least it got almost to Ireland before its coal ran out and it had to run up its sails. When the British Great Western established regular transatlantic passenger service in 1837, it still carried sail.

The American packet Savannah made the first transatlantic steamboat trip in 1819 -- at least it got almost to Ireland before its coal ran out and it had to run up its sails. When the British Great Western established regular transatlantic passenger service in 1837, it still carried sail.

How long do you suppose it took to gain the confidence to abandon the expensive backup protection of sails, masts, rigging, and extra crew? Actually, the beginning of the end of sail traces to the battle between the Yankee Monitor and the Confederate Merrimac in 1862. Of course these powered, ironclad ships didn't carry sail because they were shoreline vessels. But the Monitor had an entirely new feature: in the center of the boat, where a mast might have been, there was instead a gun turret.

At this time the conservative British admiralty was trying to replace the fixed guns on their ironclad warships with rotating turrets. Their problem was that masts and rigging interfered with the field of fire of a turret -- a problem that the Monitor didn't have. The British clung to sail during the 1860s and built several ships with both turrets and masts. They had a lot of problems with them.

Finally, in 1871 -- 64 years after Fulton -- they took the bold step of launching the first ocean-going warship without any sail -- the H.M.S. Devastation. It set the pattern for future British sea power, but masts were still to be found on many merchant and passenger ships well into the 1900s -- a full century after the first ocean-going steamboats.

We have to ask whether we're looking at conservation of fuel or conservatism of mind. Indeed, some naval architects today talk about adding modern forms of sail to boost the power of merchant marine vessels. But, though the engineers of the 19th century were many things, they were never conservationists. The long retention of sail represents a remarkable instance of conservatism in engineering.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This episode has been revised and expanded as Episode 1338.

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library)

A Frigate Powered by both Steam and Sail from Man on the Ocean, 1874

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library)

Isambard Brunel's Great Eastern from Man on the Ocean, 1874