Brunel -- Father and Son

Today, we meet a remarkable father and son. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The British art historian Kenneth Clark coined the term Heroic Materialism to describe the engineering of the middle 19th century. Those engineers were melodramatic artists in iron, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the grandest of them all.

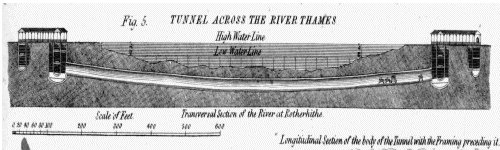

His father, Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, was born in France in 1769 and died in England in 1849. At first Marc Brunel's work was part of the wave of building characteristic of the Industrial Revolution. But he made his mark in the history books with great works of civil engineering -- an early suspension bridge, the first floating ship-landing platform, and -- boldest of all -- a tunnel under the Thames river -- the first construction of its kind, and one that required a whole new set of accompanying technologies.

The person he put in charge of the tunnel was his 20-year-old son. The tunnel was begun in 1825 and completed in 1843, after a collapse killed many workers, seriously injured the younger Brunel, and halted work for seven years. Yet the completed tunnel still serves London today.

The son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, went on to become the prototypical 19th-century engineer. He built the famous two-mile-long Box Tunnel, several major suspension and arch bridges, and 1000 miles of railway; and with each project he expanded civil engineering techniques far beyond anything that had been known or imagined.

But his crowning achievements were his steamships. In 1837 he produced the paddle-driven Great Western -- one of the first transatlantic steamboats in regular service. He followed it with a screw-propeller-driven steamship called the Great Britain.

Then he bit off a mouthful that not even he could chew. In 1853 he began work on the Great Eastern -- the grandest ship the world had ever seen. Designed to take 4000 passengers to Australia and back without refueling, it was 700 feet long and weighed 20,000 tons.

The Great Eastern was launched in 1858, and Brunel died of stress and overwork the next year. It was all it was meant to be, with one catch: it was only one quarter as fuel-efficient as Brunel had expected, and that killed it as a passenger liner. But it did find its place in history when it proved to have the ideal capacities for laying the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

The younger Brunel really trod the world in seven-league boots of his own making. He made engineering larger than life and set the mood for the technology of his century. Never before or since have we reached such glorious self-confidence in our ability to make the unimaginable.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Clark, K., Heroic Materialism. Civilisation. New York: Harper & Row, 969, Chapter 13.

This episode has been heavily revised as Episode 1405.

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)

Cross-Sectional View of Brunel's Thames Tunnel.

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library)

Isambard Brunel's Great Eastern (from Man on the Ocean, 1874)