Kurt Vonnegut

by Andrew Boyd

Today, so it goes. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I didn't altogether miss Kurt Vonnegut but I was late to the party. As a pre-teen and then teenager, I gobbled up any science fiction I could get my hands on. From the scientific precision of Arthur Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama to Huxley's politically charged Brave New World, I lost myself in them all.

U.S. Army portrait of Pvt. Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

[Wikipedia image/U.S. Army photo]

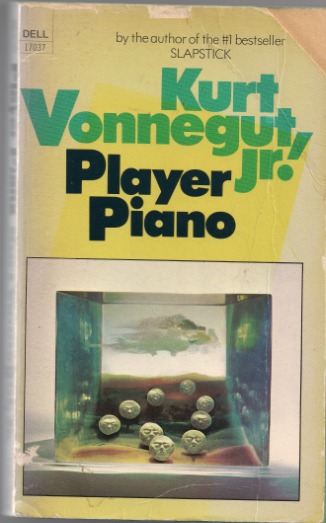

But I didn't run into Vonnegut until late in college when my future wife suggested I read Player Piano. The novel was written in 1952, long before industrial robots had found their way to the shop floor. It depicts a world where virtually every job requiring manual labor has been relegated to machines, thus robbing the masses of a chance to do meaningful work. The social hierarchy is topped by a combination of managers and engineers, the latter to keep the machines running.

Having grown up in an era where engineers were measured by the contents of their pocket protectors, I found the idea of engineers rising to prestige and prosperity quite funny; that is, until Bill Gates became the world's richest person. (Without, I might add, shedding the persona of an unrepentant geek.)

Vonnegut's voice was unlike anything I'd previously encountered, with the possible exception of J. D. Salinger's in Catcher in the Rye. Vonnegut spoke plainly, as did his characters, though not without irony.

Vonnegut suffered a series of personal tragedies but still managed to keep his humor. His mentally ill mother took her life while he was still in his early twenties. When his sister died of cancer and his brother-in-law in a train accident, Vonnegut and his wife adopted the three orphaned children.

While serving as a soldier in the Second World War, Vonnegut was captured and imprisoned in Dresden. There he experienced the intense Allied firebombing that killed tens of thousands and leveled the city. Vonnegut managed to survive because he was detained in an underground locker on the grounds of a meat packing plant. The locker, known as Slaughterhouse Five, later became the title of one of his most highly acclaimed novels. Shocking. Satirical. Sad. Funny. Slaughterhouse Five was a blend of memoir and novel tied together in Vonnegut's own, unholy style.

And sitting prominently in the middle was science fiction. As the protagonist randomly jumps about in time, he experiences war, death, and capture by Tralfamadorians — friendly, four-dimensional aliens shaped like toilet plungers. Pulling all that off takes the work of a seriously creative mind ...

Science fiction freed Vonnegut to provide his own peculiar social commentary — commentary that frequently involved engineers and scientists. His Player Pianomusings about the role of machines and engineers certainly seem to be coming true. I hope, and suspect, we'll have a chance to write a happier ending than Kurt Vonnegut did.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Notes and references:

The phrase 'so it goes,' used in the opening of the essay, was frequently employed by Vonnegut.

K. Vonnegut. Player Piano. New York: Scribner, 1952.

K. Vonnegut. Slaughterhouse Five. New York: Dell, 1969.

D. Smith. 'Kurt Vonnegut, Novelist Who Caught the Imagination of His Age, Is Dead at 84.' New York Times, April 12, 2007. See also: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/12/books/12vonnegut.html?pagewanted=all&_r=2&. Accessed October 15, 2013.

The picture of the cover of Player Piano is by E. A. Boyd. The remaining pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.

This episode first aired on October 17, 2013.