Pierre Fauchard

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a profession comes of age. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It's no surprise that professions evolve. Sometimes the evolution's no less remarkable than creatures rising up from a primordial swamp to take their place on land. Such is the case with dentistry.

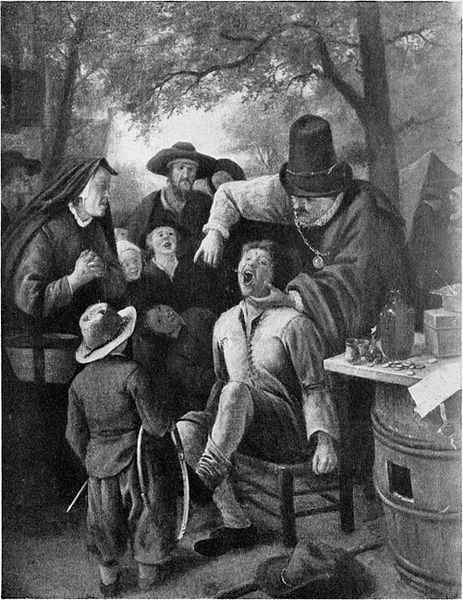

For much of history dentistry was barbarous. Crude tools. No anesthesia. Rules and standards didn't exist. Anyone who wanted to practice dentistry was free to do so. Dentists developed their own, individual techniques, and guarded them as a means of competitive advantage.

Enter Pierre Fauchard. Fauchard was born in 1678 to a family of modest means in Northern France. At age fifteen he entered the French Royal Navy. There he learned first-hand about mouth disease, in particular problems brought about by scurvy.

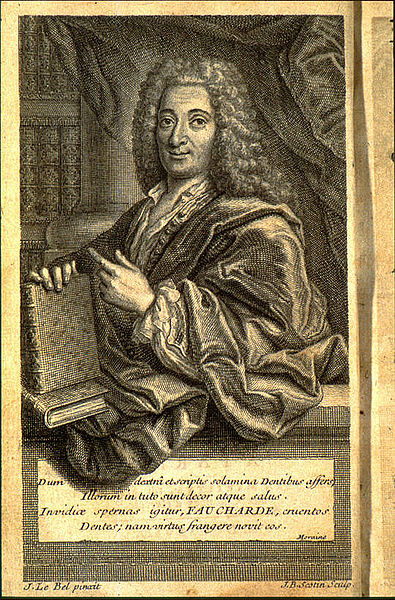

Portrait of the father of modern dentistry Pierre Fauchard.

Engraving made by J. Le. Bel

After three years Fauchard left the Navy and set up a dental practice at the University of Angers Hospital, two-hundred miles southwest of Paris. There he practiced his trade, cultivating new techniques and refining others. Fauchard worked diligently and with conviction, and he slowly developed an outstanding reputation.

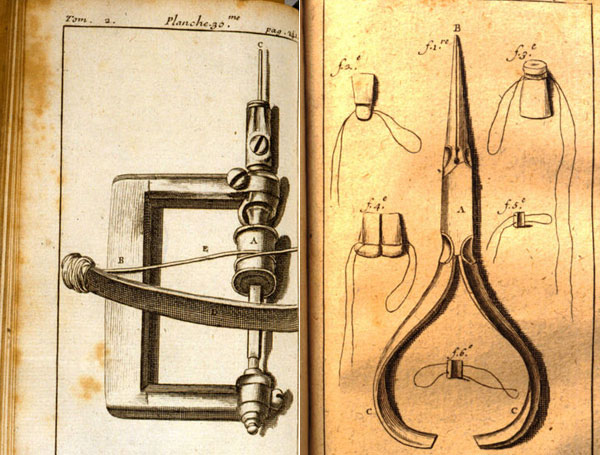

His achievements were many. Based on observations with a microscope, he correctly refuted the theory that tiny worms were the cause of dental decay. He observed a correlation between sugar and tooth decay, and recommended limiting sugar intake. Fauchard was an advocate of filling cavities after they were drilled and worked on developing his own filling materials. He freely borrowed instruments from watchmakers and jewelers, modifying them as he needed. Fauchard recommended working on patients while they were seated and the dentist standing, rather than using the common practice of the dentist sitting on the patient's chest on the floor, head cradled between the dentist's knees.

But Fauchard's most lasting contribution came late in his career. Twenty years after starting his practice, Fauchard moved to Paris. There he discovered that the world's leading medical libraries didn't have good textbooks on dentistry. So he wrote one. Entitled The Surgical Dentist, the work consisted of two volumes and totaled more than eight-hundred pages. Diagrams. Descriptions. The book was carefully reviewed and edited. As a result of both its content and Fauchard's reputation, the book spread throughout Europe and became the foundation of dentistry.

From left to right: drill and tooth extractor drawings from "The Surgical Dentist"

A century and a half after his work was published, Fauchard was hailed at a distinguished gathering of dentists as having opened a "new era in the history of [the dental] profession." Proclaimed one leading scholar, "The name of Pierre Fauchard, upon whom the title Father of Modern Dentistry has justly been bestowed, will endure ... [for] having so altruistically and successfully raised the practice of dentistry from an indifferent trade to a dignified profession..." And, I might add, for having made trips to the dentist a lot less frightening.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For a related episode, see DENTISTRY.

C. D. Lynch, V. R. O'Sullivan, and C. T. McGillycuddy. 2006. "Pierre Fauchard: The 'Father of Modern Dentistry.'" British Dental Journal 201, 779-781. See also: http://www.nature.com/bdj/journal/v201/n12/full/4814350a.html. Accessed April 2, 2013.

Pierre Fauchard. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Fauchard. Accessed April 2, 2013.

All pictures are from Wikimedia Commons. The picture of the drill and the tooth extractor are images from The Surgical Dentist.

This episode first aired on April 4, 2013.