The Scientists Speak

Today, scientists speak as WW-II ends. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run and about the people whose ingenuity created them.

Old books seem to cling to me like autumn leaves. Here's one that I'd thought was junk. But, the other day as I was fixing to toss it, I paused to turn some pages. Good thing I did! It's The Scientists Speak from 1945 -- 79 short essays by great engineers and scientists of that time. Each seeks to tell us where some facet of science is headed. Of course, that's a fool's game. Futures are unknowable, especially those molded by the creative imagination.

Many of the writers are aware of that fact. Irving Langmuir (who won a Nobel Prize for his work on surface chemistry) describes his earlier invention of the gas-filled light bulb. He takes pains to tell us that such advances do not result from planning. Rather, they're born of future-changing momentary insights.

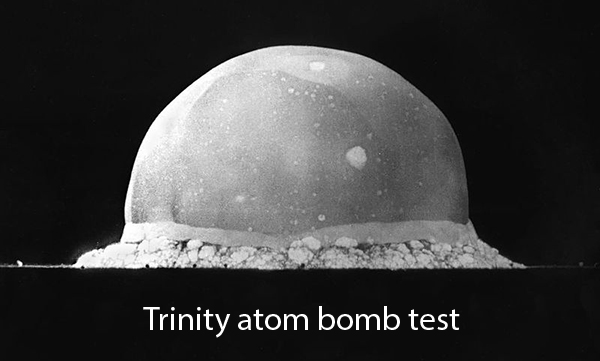

The elephant in the room back then was J. Robert Oppenheimer. He is searingly to-the-point: He says that the atom bomb, whose development he led, revealed no new scientific principles, nor was it a research tool. It was a weapon. And any new weapon, once it exists, will be used again. He simply utters a plea that we build a world "... united, in law, in common understanding, in common humanity, before a common peril."

Edwin Hubble, known to us for the space telescope that's so justly named after him, was a great 20th century cosmologist and student of nebulae. He writes about "The Exploration of Space." But he means telescopic, not vehicular, exploration. He describes the path by which our understanding of the universe has expanded, and will keep expanding. "Slowly," he says, "as the darkness recedes, the universe will loom forth." Well, the telescope named after himhas certainly vindicated that remark.

Most of these people merely tell us that their area has done much for us and is poised to do much more. True enough, I suppose, but not especially useful. Helicopter inventor Igor Sikorsky oversteps himself when he predicts private commuter and taxi helicopters.

Biology might be the weakest section. Small wonder -- the discovery of the DNA molecule would soon turn that field on its axis. Cytologist T. S. Painter comes close when he tells us that the study of human genes will be important. But then, all these greats faced an impossible task. The wisest of them simply tell us where we are, then suggest a mindset with which to embark on the great ferment of the post war period.

Perhaps Polaroid inventor Edwin Land does that better than any. He finishes with a statement that I find true and powerful. He says,

"... applied science, purposeful and determined, and pure science, playful and freely curious, continuously support and stimulate each other. The great nation of the future will be the one which protects the freedom of pure science as much as it encourages applied science."

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Scientists Speak. Warren Weaver, ed. (NY: Boni & Gaer, 1945/'46/'47)

See also the many links within the episode for more back-story on the people I mention. I should also point out that the book makes no mention at all of the digital computer. Atom bomb image courtesy of Wikemedia Commons. Hubble telescope photo courtesy of NASA.

This episode was first aired on April 5, 2013