Technology's Punctuated Equilibrium

Today, technology's punctuated equilibrium. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I feel like a zoologist looking for new kinds of creatures when I sort through old aeroplanes. Evolution tries every combination, then settles on those that work best. Same with technology: Think about the jets we fly today. They have the same general form as those we flew in the late 1950s. Only the engines move about a bit, some on the wings, others to the rear of the body. The airframes themselves are pretty well settled.

We ran through all the changes of airplane forms from the beginning until WW-II. Then change slowed dramatically. A few major ideas like the V-tail and the swept-back wing struggled for ascendancy. But the mad trial and error of the early years ended.

We've watched many new technologies come into being since then, and it's been the same story. Take the software-served personal computer: The ability to multitask among various programs was a huge advance - or the idea of opening a new window on each task. Then we tied computers to the world through the Internet.

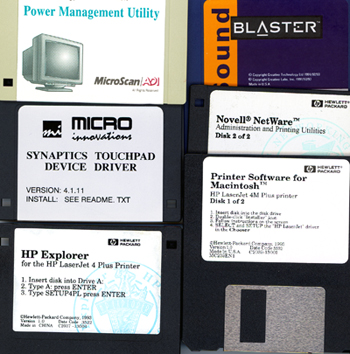

But, as with airplanes, the mad flurry of early evolution slowed. During the '80s, I'd go to software stores each Saturday, looking for some new surprise. I'd bring my shrink-wrapped magic home and patiently load it. It was seldom the panacea I'd hoped for. Still, now and then one really did change the way I worked. And we lived for each magical stage of PC evolution.

But, as with airplanes, the mad flurry of early evolution slowed. During the '80s, I'd go to software stores each Saturday, looking for some new surprise. I'd bring my shrink-wrapped magic home and patiently load it. It was seldom the panacea I'd hoped for. Still, now and then one really did change the way I worked. And we lived for each magical stage of PC evolution.

Now our computers have stabilized. Software still evolves, but much less radically, much less visibly. Now we peer through the looking glass of our computers into a vast Internet. We've so far exceeded our old expectations of software as to forget about it. Our expectations have gone on to other things.

That's how it was with pilots in the 1920s. They hoped to be able to get us from New York to Seattle in an air journey of ten or twelve legs -- a trip that'd take two days and cost a month's pay. Now we routinely make such trips in one hop and a matter of hours. Sure, airplanes might someday halve the time it takes to cross the country. But that'll no longer mean radical change.

We likewise forget about our PC software, and ask instead what new delight we might find in that rabbit hole called the Internet.

Evolutionists talk about punctuated equilibrium -- the idea that evolution reaches a point where some influence destabilizes organisms and causes them to evolve rapidly. Then it levels out, and change is incremental for a long time. Technology plays that same idea out, but on a time scale we can experience.

And we are hooked. Where will the next sunburst of radical evolution occur, and in what technology? We surely want the sheer raw pleasure of riding each new wave as it arrives. Now it's what -- social networking, cameras, telephones? And as they level out ... what next? We don't know. But, blessing or curse, it's in our blood that we can hardly wait for it to appear.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the Wikipedia article on Punctuated Equilibrium.

Some listeners will want to point out that airplane experimentation is not dead. The airplanes of Burt Rutan, for example come to mind -- as do many other forms that straddle the thin line that separates space vehicles from atmospheric airplanes. Evolution, whether inventive or biological never stops. However, the aircraft in common use have outwardly changed little in the past half century.

Photos above by J. Lienhard. Photo below courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

The asymmetrical Blohm & Voss BV-141 was a radical German airplane design made during WW-II.