Heligoland

Today, we visit Heligoland. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Germany has two stretches of coastline. The larger one lies below Denmark and Sweden on the Baltic Sea. The other is the L-shaped Frisian Coast. It stretches along the North Sea from Holland to Denmark. Nestled in that L, thirty miles from the coast, is the tiny archipelago of Heligoland.

Heligoland is made up of only two islands. The larger is four-tenths of a square mile, the smaller, only a quarter square mile. The name comes from the old word Heyligeland or Holy Land since it was once associated with a Pagan god. Various neighboring countries owned it until Great Britain finally ceded it to Germany in 1890. It had, by then, been serving as a seaside resort area for almost a century.

Heligoland is little-known in America today. But I heard a lot about it in the near wake of WW-I, and during WW-II. Germany made it into a Naval Base. And an early WW-I naval battle took place around it. The British beat the Germans badly and limited German Naval action for the rest of that war.

Heligoland again became a resort after the war. And, in June 1925, young Werner Heisenberg, driven to distraction by hay fever, retreated there. He needed to focus on the puzzling implications of the new quantum physics. There, in that sun-washed, sea-lapped land of red rock, white sand, and green fields, he found his Eureka moment. He set the understanding of known quantum behavior. And the next few years formed the great sea change of modern physics.

Then the NAZIs came. Heligoland again became a military base. Late in the war, allied planes poured countless tons of explosives upon it. The civilian population first lived underground, then was finally evacuated.

Soon after the war, the British set off the largest non-nuclear, man-made explosion there -- seven kilotons, about half the size of the Hiroshima bomb. It was meant to permanently remove German fortifications. Well,it did that. And it created a permanent dent across the middle of the larger island.

Now Heligoland is once more a resort. People walk the sands and admire basking seals and sea lions, gannets and gulls. Cruise ships move past the great red rock cliffs that overlook the sea.

Matthew Arnold once wrote about a place like this, across the North Sea on the English shore. He began, "The tide is full, the moon lies fair." But then he segued into another theme. He recalled how it had been, and would be again, "Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight/where ignorant armies clash by night."

And, looking at Heligoland, we think of Heisenberg shaping a majestic science there -- then, later, almost managing to build a German atom bomb upon those very ideas. History's tides do indeed wash, back and forth, over those tiny islands in the North Sea.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Seee the Wikipedia articles on Heligoland (spelled Helgoland in German), The Battle of Heligoland Bight, and Werner Heisenberg.

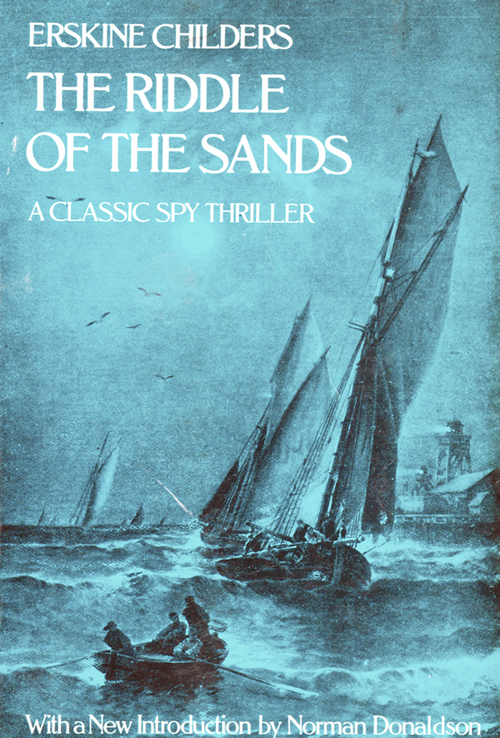

My attention was drawn to the Frisian Coast by a fine 1903 book that described the natural beauty of the Frisian coast under the cloud of impending war: E. Childers, The Riddle of the Sands. (New York, Dover Pubs. Inc., 1976/1903). Childers spins a story of two young British men exploring the Frisian coast in a sailboat where they discover a German plot to use the coast's odd geography as a base for invading England.

The Matthew Arnold poem that I quote is Dover Beach. Estimates of the magnitude of the 1947 explosion vary. Seven ktons is an upper estimate. The resulting "dent" that I mention is the flat section just beyond the red and white transmission tower on the right side of the photo above (photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).