Galileo, the Church, and the Vatican Library

by Andrew Boyd

Today, of science and scripture. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Galileo's dealings with the Roman Catholic Church are well documented. The man hailed as the father of modern science believed the earth went around the sun. To the Church this was heresy. Galileo was ultimately forced to publicly renounce his belief in a sun-centered system, and spent the last decade of his life under house arrest.

Galileo's is arguably the most famous tale of the Church's efforts to stamp out science when it conflicted with scripture. And it's led scholars to ask: how is it that science came to flourish in such a hostile environment? The scientific revolution could have occurred at many different times and places — times and places that didn't include the Roman Inquisition. Why did it happen when and where it did? That's a huge question, and not one we're going to tackle today. But back to the Church. Why was it so hostile toward science? In fact, it wasn't. It frequently went out of its way to support science. And nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the Vatican library.

By the fourteenth century, Rome was nothing more than a medieval village set in the crumbling remains of a once great city. Church leaders set out to rebuild, drawing upon the blossoming artistic and architectural developments of the Renaissance.

One of the prominent leaders of the fifteenth century was Pope Nicholas V. Nicholas oversaw his share of civil engineering projects. But he had a great love of knowledge, and especially, books.

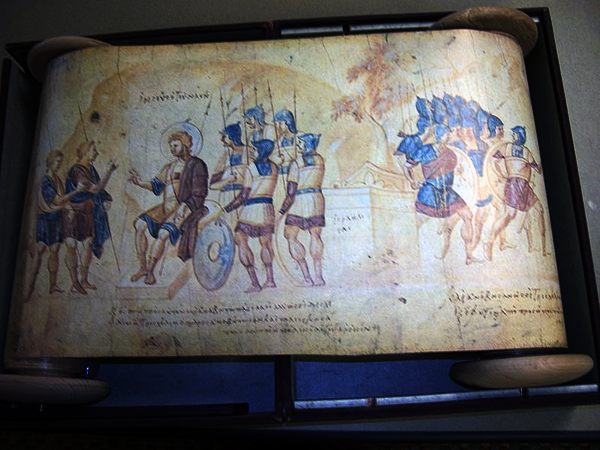

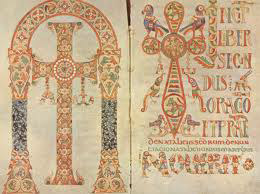

Nicholas wanted to build one of the world's great libraries. He sent emissaries throughout Europe in search of forgotten manuscripts. The library became a center for recovering ancient Greek texts, including works of mathematics, astronomy, and geography.

And most importantly, the library wasn't locked away, but was created 'for the common convenience of the learned.' With its many texts openly available, the Vatican library actually helped power the Renaissance — a period overflowing with emphasis on reason and empirical evidence. Galileo was unsurpassed in using empirical evidence to make his arguments. Unfortunately, when that evidence collided with scripture, evidence got the worst of it.

But not forever. In Galileo's case we have a happy ending. Two centuries after he was thrown in jail, the Church's index of prohibited books no longer included Galileo's once heretical writings. Another two centuries, and Pope John Paul II praised Galileo as a 'brilliant physicist' and admitted the 'error of the theologians at that time.' Sometimes the wheels of progress turn slowly. But they do turn.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

Catholic Church and Science. From the Wikipedia Web site: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_and_science#Galileo_Galilei. Accessed March 8, 2011.

Pope Nicholas V. From the New Advent Encyclopedia Web site: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11058a.htm. Accessed March 8, 2011.

Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library and Renaissance Culture. From the Web site of the U. S. Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/vatican/. Accessed March 8, 2011.

The picture of the Vatican library is from the Flickr Web site. The pictures of Vatican library manuscripts are from the Wikimedia Commons Web site.