Hugh Everett: The Physicist, The Man

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a tragedy in at least one universe. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

By 2007 it was one of the most widely accepted views of our universe. But fifty years earlier, when it was first introduced, it was ridiculed.

In the mid 1950s, a young graduate student named Hugh Everett submitted a doctoral thesis to his advisor at Princeton. The advisor was impressed. Everett had tackled the most philosophically challenging problem in all of quantum mechanics and arrived at a remarkable interpretation. He explained away the fact that tiny entities like electrons seem to act like waves until we look at them, at which point we see particles. That's utter nonsense in our macroscopic world. Waves on the lake don't suddenly turn into stones on the shore just because we show up for a swim.

But Everett's mathematics carried its own set of baggage. For his interpretation to work, we have to accept an infinite number of parallel universes — with the number growing all the time. That's a lot to swallow. But it's not why Everett's ideas were initially dismissed.

Everett's thesis advisor had been a student of the great Niels Bohr, one of the most influential figures in the history of quantum mechanics. Thanks to his advisor's connections, Everett had the chance to discuss his own interpretation of the quantum mechanical universe with Bohr on numerous occasions. Bohr, who was a vehement defender of his own interpretation, could not be convinced.

Due to countless criticisms, from Bohr and others, Everett's thesis was whittled down to one-fourth of its original length at the direction of his advisor. The resulting work was politically correct but much of the content had been excised. The original version had to wait fifteen years before it was published.

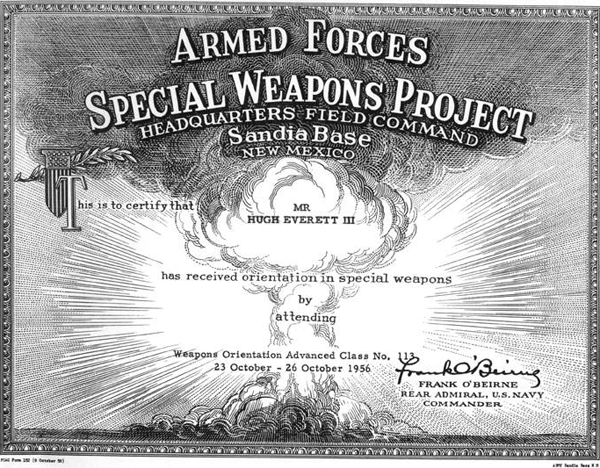

Jilted, Everett turned his back on the physics community. Instead, he did highly classified work for the Pentagon, using early computers to evaluate nuclear attack strategies between the U.S. and Soviet Union. The work proved technically interesting and the money was good, feeding Everett's self-absorbed personality.

Training certificate issued by Special Weapons Evaluation Group at the Pentagon in 1956

At Everett's insistence, he and his wife engaged in 'spouse-swapping.' When not swapping, he freely philandered. The Everett's two children grew up without meaningful parental restrictions, and their daughter took her own life at age thirty-nine after a lifetime of drugs and depression. For Hugh Everett, years of smoking, three martini lunches and dinners, and hedonic eating habits took their toll. He died in 1982 at the age of fifty-one of a heart attack, never seeing the full impact of his universe shattering ideas. It's a tragic story. But we have to ask, of whose making?

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Notes and references:

For related episodes, see THE BOHR-EINSTEIN DEBATES, THE DOUBLE SLIT EXPERIMENT, and DETERMINISM AND THE MANY WORLDS INTERPRETATION.

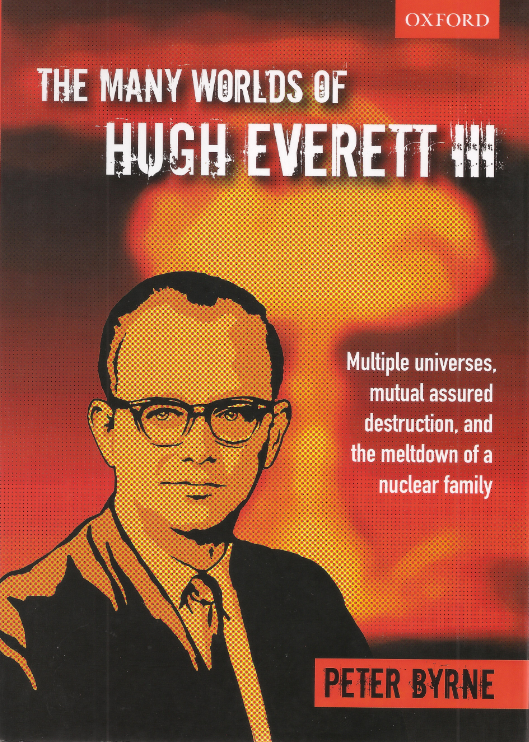

P. Byrne. The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett III: Multiple Universes, Mutual Assured Destruction, and the Meltdown of a Nuclear Family. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. The book was authorized by Hugh Everett's son, Mark, who made years of previously unreleased family papers available to Byrne.

The picture of the certificate earned by Everett is from Wikimedia Commons. The picture of the book jacket is by E. A. Boyd.