The Bohr-Einstein Debates

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a clash of titans. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

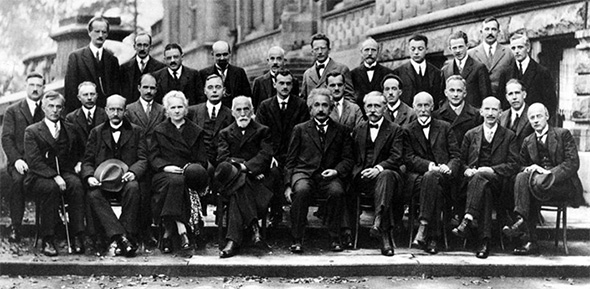

It was one of the most famous scientific meetings in all of history. Seventeen of the twenty-nine attendees had either received or would receive Nobel prizes. But what made the conference so memorable was a disagreement — a disagreement between two of the titans of physics: Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein.

The year was 1927, and physicists were puzzled. At question was the very nature of the extremely small. Were electrons, light, and similar entities waves or particles? In some experiments, the tiny entities behaved like waves, while in others they behaved like particles. That's just not possible in our macroscopic world. Sound waves don't behave like pebbles — and thankfully so, or your ears would be stinging right now.

The 1927 conference on quantum mechanics was held to discuss how the many seemingly contradictory observations could be reconciled. Schrödinger and de Broglie showed up with their ideas. But the eight-hundred pound gorilla was Bohr. In what later came to be called the Copenhagen interpretation, Bohr proposed that wave equations described where entities like electrons could be, but, the entities didn't actually exist as particles until someone went looking for them. The act of observation caused existence. In Bohr's own words, the entities in question had no "independent reality in the ordinary physical sense."

Einstein wouldn't have any of it. An electron was an electron, and just because someone wasn't looking at it, it was still there — wherever "there" happened to be. Late in the conference, Einstein rose to challenge Bohr's views. But that was only the beginning. Until Einstein's death some three decades later, Bohr and Einstein entered into spirited debates — in print and face to face. The debates were gentlemanly. Bohr and Einstein were friends and had great respect for one another. But they were also stubborn. "It is wrong to think the task of physics is to find out how nature is," said Bohr. Einstein disagreed. "What we call science," he said, "has the sole purpose of determining what is."

Through all its strangeness, Bohr's Copenhagen interpretation remains one of the most widely accepted worldviews of quantum mechanics. Other common interpretations are seemingly even more bizarre. But they all point to one, simple fact. Our universe, as any physicist will tell you, is a mysterious place. It teases us with unimaginable facts then leaves us to make sense of them. Perhaps someday, we will. But until then, we'll just have to savor the great mysteries that surround us.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

Bohr was not the sole voice of the Copenhagen interpretation, even at the time of the fifth Solvay conference in 1927. Heisenberg and Pauli, who often worked with Bohr, were also strong advocates and worked diligently to defend the Copenhagen interpretation as Einstein sought to poke holes in it. It is referred to as "Bohr's Copenhagen interpretation" for clarity in reading, as suggested by Dr. Sarah Fishman (Boyd).

The quotations in the episode can be found in Quantum, pages 262 and 320.

M. Kumar. Quantum. New York: Norton, 2010.

All pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.