Horatio Alger

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a Horatio Alger story. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

He's a young boy living on the streets. He has little or no education, but he's bright, honest, and industrious. And by the end of the book, he's achieved "success." "He" is the hero in any of dozens of books penned by Horatio Alger, whose name is synonymous with rags to riches tales.

Alger was born in 1832. Son of a Unitarian minister, he attended Harvard where he studied with such noteworthy writers as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Alger sought to make a living as a serious writer, but made little headway. So ten ye ars after leaving Harvard, he returned, this time to attend the Divinity School. He eventually took a position as a Unitarian minister.

ars after leaving Harvard, he returned, this time to attend the Divinity School. He eventually took a position as a Unitarian minister.

And here the story takes an abrupt turn. Shortly after his appointment, word surfaced that Alger had engaged in acts of "unnatural familiarity" with boys in the congregation. When confronted with the charges, Alger admitted simply to "imprudent" behavior, resigned, and left town.

Following a brief stay with family, Alger settled in New York where he again pursued writing. He was moved by the plight of boys who lived and worked on the street and found himself drawn into their world. Alger sought to establish programs to feed and house street boys, and he personally mentored scores of young men. His experiences in New York, coupled with his religious training, led him to write his inspirational "Horatio Alger" stories.

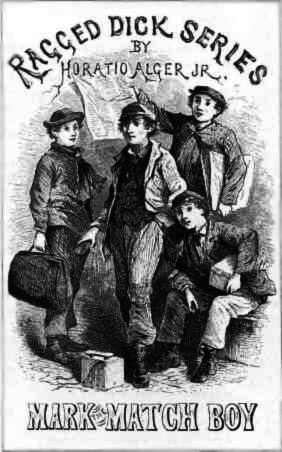

Alger's first such story, Ragged Dick, received some critical acclaim. But the stories that followed were formulaic. A young boy as hero. A patron who guides the boy. Young bullies who resent the hero's achievements as he strives to better himself. Alger's books weren't great literature. They were Cinderella stories, albeit with hard work standing in for the fairy godmother.

So who was Horatio Alger: sinner or saint? Lack of historical source material makes it hard to say. But historians point to a poem written by Alger in his waning years, Friar Anselmo's Sin, which may well express Alger's own perspective on his life:

Friar Anselmo (God's grace may he win!)

Committed one sad day a deadly sin;

Which being done he drew back, self-abhorred,

From the rebuking presence of the Lord'

Anselmo's heart is heavy. But even with his burden, he tends to a wounded traveler, who he later learns is an angel in disguise. The angel proclaims:

'Courage, Anselmo, though thy sin be great,

God grants thee life that thou may'st expiate''

Henceforth, he strove, obeying God's high will,

His heaven-appointed mission to fulfill.

Thus ends the tale of Friar Anselmo.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

J. A. Geck. The Novels of Horatio Alger, Jr.

G. Scharnhorst. 1985. The Lost Life of Horatio Alger, Jr. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1985.

The picture of books on a shelf is from the Flickr Web site. All other pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.