Lucretius

Today, Roman atoms. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Titus Lucretius was a Roman philosopher -- an Epicurean -- born thirty years before Cleopatra. He left few tracks. Contemporaries mention him here and there. St. Jerome wrote some lurid stuff about him 4th century -- probably hearsay. Cicero wrote about him and called him a genius.

But Lucretius's only surviving work was one whose greatness Cicero could not've fully understood. The ideas in it weren't backed up by hard science until 150 years ago. This last work (which he probably hadn't finished editing when he died) was a 200-page poem: De Rerum Natura -- On the Nature of Things.

As we read, we catch Lucretius's clear mind and his Epicurean simplicity. We've turned the word Epicurean upside down in our time. But those Epicureans weren't students of fancy food. What they believed was that things are what they seem to be -- that our senses don't deceive us. And they scorned the mystery-laden polytheism of Rome.

So Lucretius watched matter dividing, subdividing, and rejoining in the world around him. He concluded that matter must be made of very small building blocks, of atoms, that form and reform. The Greeks had flirted with atomism. But Aristotle's earth, air, fire, and water essences had overshadowed atoms 300 years earlier, and they would do so until modern times.

Lucretius's ideas flew in the teeth of Aristotle's. He couldn't win -- not then. His work survived only because it had another dimension. He was a superb poet. Writing in simple direct Latin was an uphill battle. It wasn't good for handling complex ideas. But he reshaped Latin and created beauty on the way. Listen as he paints a modern picture of atoms moving in solids and gases.

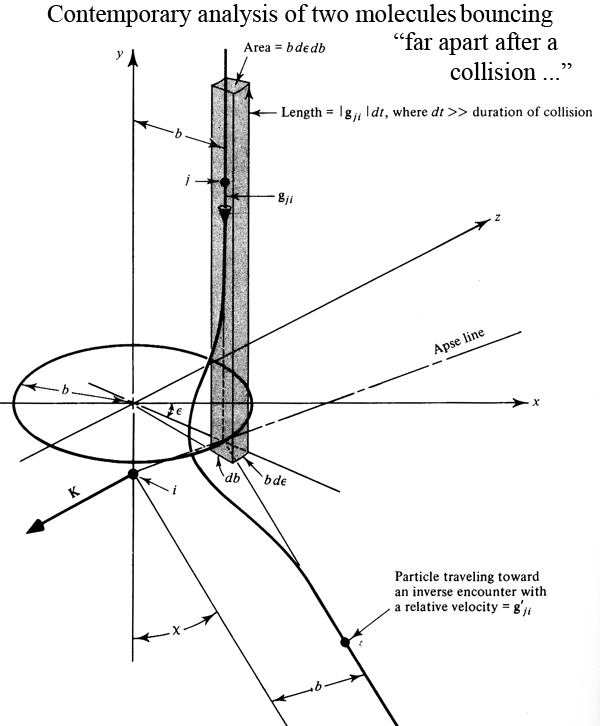

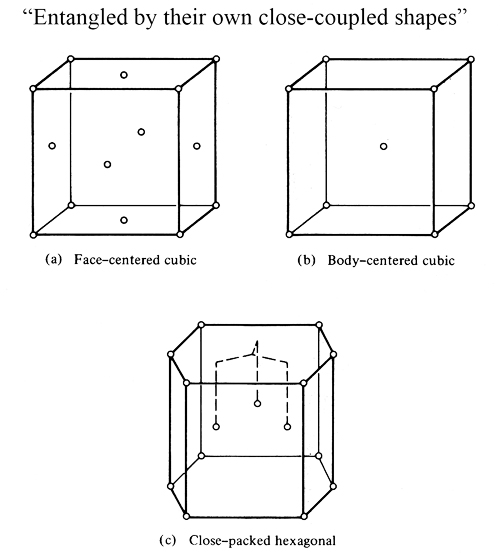

... no rest is allowed the atoms moving through the depths of space. Driven along in an incessant but variable movement. Some of them bounce far apart after a collision [while others] recoil but little. Entangled by their own close-coupled shapes, they make strong rooted rock or the bulk of iron.

When we read 19th-century physics books, we're amazed at how they mirror Lucretius's language.

His poem was standard classical literature when Aristotle's science began crumbling in the 1600s. Finally a French cleric named Pierre Gassendi broke with Aristotle. He began creating a modern kinetic theory of gases. Gassendi began right where Lucretius's poem left off.

The poem is such a rich trove of ideas -- ideas out of place in time -- modern ideas about heat -- Galilean ideas about falling -- ideas that would've been bypassed and forgotten. The crowning irony is that Lucretius's ideas were handed down to us, not on their enormous merits, but only because they were so beautifully said.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This is greatly revised version of Episode 334. Two translations of Lucretius: Lucretius, Lucretius on the Nature of Things (Trans. by C. Bailey). (London: Oxford University Press, 1929). And Lucretius, Lucretius on the Nature of Things (Trans. by R.E. Latham). (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1968.)

See also the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Dictionary of Scientific Biography articles on Lucretius, and the relevant Wikipedia articles. For an account of how this played out subsequently, see C. L. Tien and J. H. Lienhard, Statistical Thermodynamics. (New York, Hemisphere Publishing Co., 1971/1979). To read this on line, Click Here. All illustrations are from this source.