Buffalo vs. Wildcat

Today, the texture of change. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've been asked why I say so much about airplanes. It's because early flight reveals the texture of technological change in a most remarkable microcosm. In 1935, the great architect le Corbusier said of airplanes, "No door is closed. Everything is relative. ... If a new factor makes its appearance, the relation alters. ... In aviation everything is scrapped in a year."

That situation is far less fluid -- far less interesting -- today. The Air Force still flies B-52 bombers after sixty years of service. You and I ride in airplanes not much different from those we flew in the '60s. The rate of change was dizzying when le Corbusier wrote. Then it began slowing down.

That fact came home to me last week in the National Museum of the Pacific War. I found a badly-damaged Grumman Wildcat fighter in an alcove, as it might've been abandoned on Guadalcanal.

Wrecked Grumman F4F Wildcat in the National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, TX. (Photo by J. Lienhard)

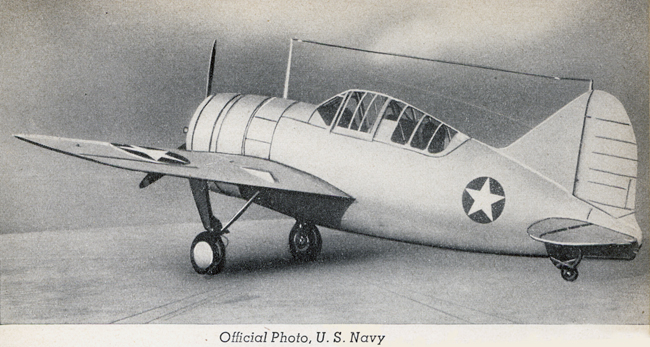

The Wildcat was a stubby mid-wing monoplane, barely distinguishable from another plane, the Brewster Buffalo. The Buffalo was nicknamed Beer Barrel because of its squat shape. Still, I had to go back to my old WW-II airplane spotter books to tell the two apart. But look under the skin and we find change taking on a new texture.

The US Navy had four aircraft carriers in 1935 and needed better planes to fly off their decks. So Brewster provided the new state-of-the-art F2A Buffalo: retractable landing gear, speeds over 300 miles-an-hour, stressed aluminum skin ...

The Brewster Buffalo F2A-2 as represented in a 1943 Warplane Spotter's Manual put out by the National Aeronautics Council, Inc.

Then, trouble: its landing gear tended to fail on carrier decks. Maintenance was too finicky. When the Japanese attacked Midway Island in 1941, our defending Buffaloscouldn't stand up to their Zero. The Buffalos we'd sold to the British and Dutch suffered similar fates in Southeast Asia. The Navy had to retrench -- and quickly.

Grumman Aircraft looked over her shoulder at the Buffalo, improved upon it, and offered their Wildcat -- slightly faster, better landing gear, higher ceiling, and it was well-armored. It could stand a lot more punishment from the still-superior Zero.

And so it went. The Wildcat may've been better than the Buffalo, but it was obsolete from the start. Meanwhile, we'd sold 44 Buffalos to the Finns before the war. When the Soviet Union invaded Finland with their primitive biplanes, those Buffalos (now marked with Swastikas) were the superior fighters.

And I'm back in that pull-no-punches Pacific War Museum. Here's that Wildcat, next step along the way to a competitive fighter, displayed as badly-shot-up by a better Japanese plane. It is a reminder of how desperately we had to change and shift in the face of an enemy who would not be beaten by our 1941 equipment.

And I'm back in that pull-no-punches Pacific War Museum. Here's that Wildcat, next step along the way to a competitive fighter, displayed as badly-shot-up by a better Japanese plane. It is a reminder of how desperately we had to change and shift in the face of an enemy who would not be beaten by our 1941 equipment.

Le Corbusier was right. Everything we did had to be scrapped within a year. But now, with no time to invent new technology, we could only adjust, adjust, adjust. And we'd never again see radical change the way we had in the first thirty years of flight.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the website for the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, TX, and the Wikipedia articles on the Brewster Buffalo and the F4F Wildcat.

J. Maas, F2A Buffalo in Action. (color by Don Greer, Illustrations by Perry Manley) (Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1996), No. 81.

For more on the texture of technological change see J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines. (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2006)