Maria Telkes

by Andrew Boyd

Today, here comes the sun. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

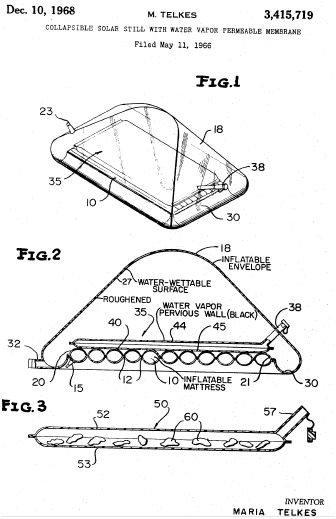

In the early 1940s, Maria Telkes found herself engaged in a massive effort that touched all Americans — the Second World War. A Ph.D. in physical chemistry and research associate at MIT, she was tapped by the U.S. military for her expertise in the new and growing field of solar energy. Battles in the Pacific Ocean often left soldiers stranded at sea for days, and a potential lack of drinking water posed a serious threat to their survival. Telkes developed a lightweight water distillation device that used clear plastic film and the heat of the sun. It was perfect for warm, humid, tropical latitudes, and was included in emergency medical kits.

Telkes was born in Hungary in 1900 and was fascinated by the potential of solar power from an early age. The direct sunlight falling on one square meter of ground is enough to keep ten, one-hundred watt light bulbs illuminated. Telkes wanted to capture that power and put it to work.

In 1948, she undertook perhaps her most famous project — the Dover Sun House — a completely solar powered home. The design was a breakthrough in that it used Glauber's salt to store the sun's energy. Glauber's salt melts in sunlight, accumulating energy in the process, and releases that energy in the form of heat when it cools and hardens. The salt stored the sun's energy more efficiently than available alternatives, and it caused quite a stir. Adding to the home's notoriety were its financier, sculptor Amelia Peabody, and architect, Eleanor Raymond — both successful professional women in their own right.

In 1953, Telkes was commissioned by the Ford Foundation to develop a simple-to-make solar oven for use in poor countries. It worked. In tests with outside temperatures in the sixties, her oven reached 350 degrees — good enough for baking bread or cooking a roast.

For her years of pioneering work on solar energy, Telkes received the Society of Women Engineers' inaugural Achievement Award, the Society's oldest and most distinguished prize. But despite her efforts and the efforts of many others, solar energy has yet to realize its promise. Economics, technology, and social habits all pose challenges for the growth of solar energy. Perhaps Telkes best expressed the situation in her own simple yet prophetic words: 'Sunlight will be used as a source of energy sooner or later',' she said. 'Why wait?'

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

[audio of the Beatle's 'Here Comes the Sun']

Notes and references:

D.S. Halacy, Jr. How to Build and Use a Solar Oven. First published as a chapter in Fun With the Sun. Macmillan, 1959. Reprinted with permission on the Web site of Mother Earth News.

I. Kubiszewski. Maria Telkes. From the Encyclopedia of the Earth Web Site.

M. Sherburne. The Woman Scientist and the Woman Architect. SCOPE: The Student Publication of the Graduate Program in Science Writing at MIT.

D. Simonis. Inventors and Inventions. Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2008.

The Sun House. From the Web site of the Dover Historical Society.

The pictures of Maria Telkes and the sun's rays are taken from Wikimedia Commons. The patent pictures are from the archives of the United States Patent Office.