Everyday Electricity

Today, everyday electricity. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've spoken before about the problem of the Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.Imagine being set down in early medieval England and asked to build an engine or a flying machine. I doubt we could. Any technology is a cumulative accretion of ideas. One person does not move in and create a modern world all at once. Mark Twain's book was only social satire.

Now I have Don Cameron Shafer's 1914 book on Everyday Electricity and it sheds a different light on our Connecticut Yankee. Shafer takes an earthy view of his subject. He says, "Electricity is a form of energy. It is useless to try to explain it. Neither is it necessary to ponder [various theories of] its origin."

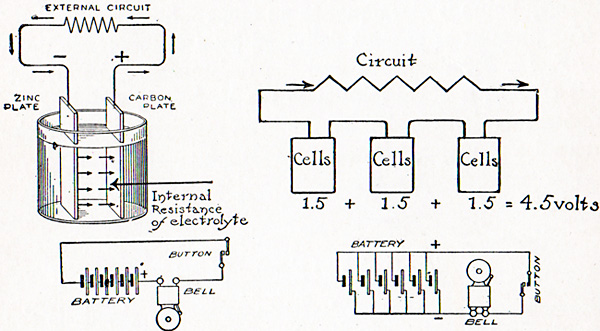

Then he plunges into do-it-yourself electricity beginning with simple batteries. Batteries are something our pragmatic Yankee might actually make. All he'd need are two dissimilar metal plates and a jug of caustic soda or salt water.

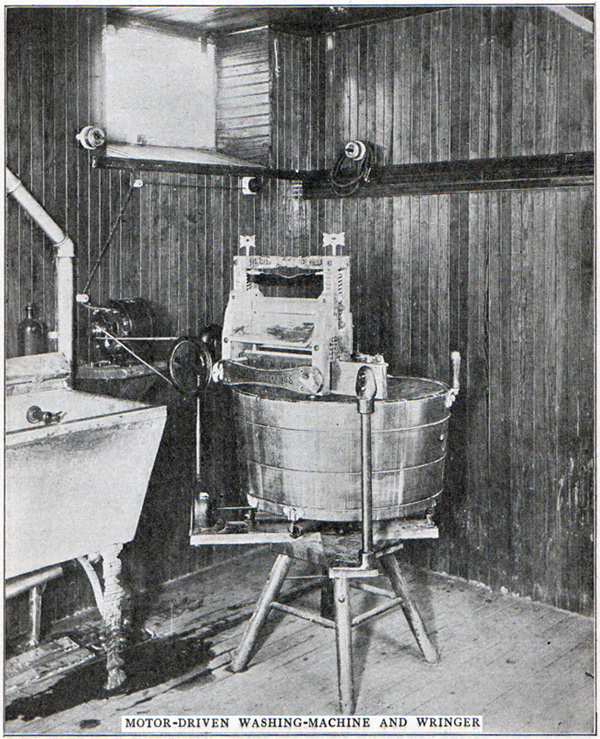

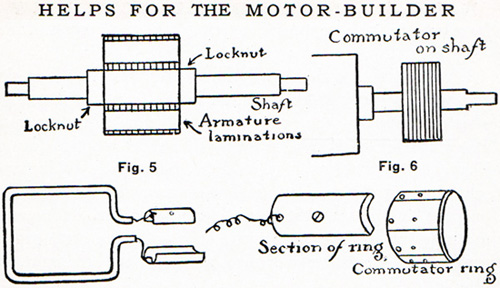

The book talks about varieties of commercial batteries, how to wire battery circuits, how to rig buzzers and alarms. But Shafer constantly pushes his reader toward building from scratch. Later in the book, he sets us to building our own electric motor. In a section on winding the armature, he says, "Nearly every one has difficulty making the first armature."

Okay, I guess we can take that at face value. But he doesn't stop there. We can build our own induction coil -- our own transformer. He tells us to "Cover the primary coils with three or four layers of heavy cotton cloth and shellac liberally."

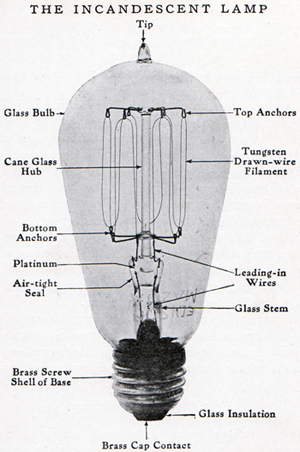

If Shafer is trying to make Connecticut Yankees of his readers, his efforts break down at a point. We're told a great deal about how to wire electric lights. But, in the end, we must buy the bulb at the hardware store. He goes on to say,

If Shafer is trying to make Connecticut Yankees of his readers, his efforts break down at a point. We're told a great deal about how to wire electric lights. But, in the end, we must buy the bulb at the hardware store. He goes on to say,

A man in Kansas purchased several electric lamps and was disappointed because they would not light. He was very much surprised when he found out that he could not use them without installing a private electric plant.

However, Shafer is not one to leave that man in the lurch. The next section of his book tells how to build a hydroelectric generator in the stream running through one's farm.

Shafer reflects the cocksure, can-do spirit of America before WW-I. When Twain wrote his Connecticut Yankee, 25 years earlier, it did badly. People did not like its grim, cynical picture of technology's inability to overcome political forces. But, by Shafer's time, it seemed that technology could take us anywhere -- politics be damned.

Still, I never did wind my own armature. And I shudder to think of opening my TV set to make a repair. Twain and Shafer alike would shake their heads if they saw today's black-boxed world. If nothing else, Shafer's book is a grim reminder of how far we've drifted from any Connecticut Yankee plausibility that we ever had.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

D. C. Shafer, Harper's Everyday Electricity. (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1914. All images are from this source.

For more on what I call The Connecticut Yankee Problem, see Episode 1021.