Measuring Race Times

by Andrew Boyd

Today, who won that race? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Whether it's luge, alpine skiing, or speed skating, the concept is simple enough: the race goes to the fastest. No judges scoring for style or technical difficulty. Just pure, unadorned speed.

But how do we know who's fastest? When runners compete, it's a matter of who crosses the finish line first. Of course, that has its own set of challenges, as captured in the 'photo finish.'

But in some sports it's easier, or a practical necessity, to race against the clock: to time competitors, and compare the recorded times to see who won. With modern technology, times can be accurately measured to better than a hundredth of a second — which is a good thing since that's often all that separates competitors.

It's pretty amazing when you think about it. Skiers zigzagging their way down a hill for more than a mile only to win or lose in the blink of an eye. Still, at the speeds winter racers travel, a hundredth of a second is noticeable. In men's luge, where speeds can reach nearly one hundred miles an hour, a hundredth of a second translates to about one and a half feet. The naked eye could easily pick a winner if two lugers were running side by side.

Before the advent of modern technology, the very process of timing was difficult. When timing a skier, for example, how did the timekeeper at the bottom of the hill know when to start the clock? The fact is he didn't. A separate, synchronized watch was kept at the top of the hill where the start time was recorded. The timekeeper at the bottom of the hill recorded only the finish time. The time down the hill was the difference between the two. And how was the time at the top communicated to the bottom? In the pants pocket of the next skier down the hill.

Watches read by a trained observer were the primary means of timing through the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. It wasn't until 1966 that the world's governing body for amateur athletics recognized electronic race times as official. Given the limitations of human reaction time, which are good to about a tenth of a second, we'll never know how many medals were handed out in error over the years. But it's a statistical certainty.

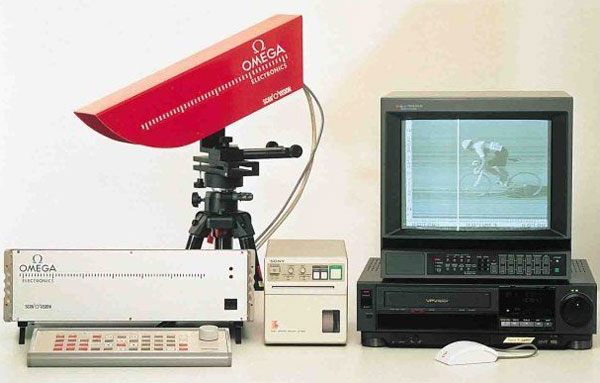

Omega, the Olympic timekeeper for close to a century, sent one watchmaker and thirty stopwatches to the 1936 summer games. For the 2010 winter games, the company supplied 220 timekeepers and information technology professionals and over 200 tons of timing, scoring, and display devices. Technology in tons. Not the usual yardstick. But however you measure it, timing technology's come a long way since stopwatches and clipboards.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For a related episode, see episode 1565, HYSPLEX.

The picture of the photo-finish device, the timing device with picture of a bicycle, and the timekeepers at a running race are taken from the Omega Moments in Olympic Timekeeping Web site. The picture of the skier is from Wikimedia Commons. All other pictures are taken from government Web sites. The bobsled pictures in particular were taken from Web sites of the U.S. armed services. Accessed February 23, 2010.