The Sweet Track

Today, a 6000-year-old roadway. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We say so much about Roman roads; we tend to forget there was ever anything before them. So let's check out a strange road, far older. It's in southwest England, between Exeter and Bristol, and was built four millennia before the Romans occupied that region.

It came to light in 1970. Raymond Sweet was cleaning drainage ditches in a peat bog when he struck a wooden plank deep in the peat. The wrong thing in the wrong place! So he took it to John Coles at Cambridge University. Coles dated it at about 4000 B.C, a major dig was begun, and a story emerged.

The trail of wood stretched on and on for a mile and a quarter -- from what'd been one island in the fen to another. This strange structure was used for a generation before reeds closed in, and peat formed over it. The peat was acidic enough to kill the bacteria that degrade wood. The wood is well-preserved.

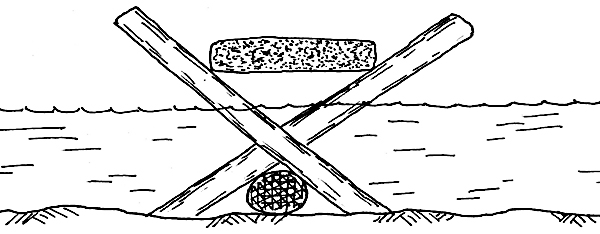

Six thousand years ago, Neolithic dwellers contrived this walkway to get across the swamp below their village. First they laid long rails of 4-inch-diameter poles on the underwater soil. Then they drove five-foot pegs into the soil at 45-degree angles. The pegs crisscrossed over the poles, forming X-shaped brackets every few feet. Finally, they fitted wide planks into the upper arms of the X, while the poles below carried their weight.

The result was a walkway, a foot above the water -- quite a piece of work for these Stone Age dwellers. Two thousand years later, the children of these engineers would build Stonehenge nearby. Tool-marks on the wood already show a fine command of carpentry. The boards were shaped by people with better tools than we would've guessed. And it took sophisticated wood-splitting technique to make them. Excavation even turned up surveyor's stakes that'd been used to lay out the path for its builders.

The result was a walkway, a foot above the water -- quite a piece of work for these Stone Age dwellers. Two thousand years later, the children of these engineers would build Stonehenge nearby. Tool-marks on the wood already show a fine command of carpentry. The boards were shaped by people with better tools than we would've guessed. And it took sophisticated wood-splitting technique to make them. Excavation even turned up surveyor's stakes that'd been used to lay out the path for its builders.

""

There's more. Artifacts, dropped along the walkway, show that these not-so-primitive people made pottery, they'd invented glue, and they traded with distant tribes for flint. The most startling artifact is an axe head, shaped from European jade. These forgotten people clearly owned some mysteries that remain mysterious.

Radiocarbon dating originally gave a range of dates for the track. Then new tree-ring dating techniques let archaeologists narrow it down to the winter of 3807 and 6 BC, when the wood was felled. Such precision gives unsettling intimacy to this old road.

So the path reveals social cohesion. It shows how these ancestors put their wills and minds together and produced a huge and unique project for the common good. The track might well've been erected in a single day by a crew of ten, using precut wood.

Artifacts have been forcing us to relearn history. Artifacts finally showed that Medieval times were a far less Dark an Age than we once thought. And, with items like this old road turning up, we see that the Stone Age included some very civilized ancestors.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 343, written in 1989 and based on the article: Coles, J.M., The World's Oldest Road. Scientific American, November 1989, pp. 100-106.

See also the 1990 New Scientist article on the Sweet Track, and the current Wikipedia article. Fragments of the Sweet Track are on display in the British Museum and the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. My photo (above) is from the Cambridge museum.