Children and their Goals

by Andrew Boyd

Today, president, pope, astronaut. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Grade school children are a delight. They're old enough to reason, but aren't yet held captive by their hormones.

Years ago, I asked a young student what he wanted to be when he grew up. He looked at me with great sincerity and answered "the president, the pope, and an astronaut." I chuckled, but only to myself. I knew he'd eventually realize what a task he'd set out for himself, but I had no desire to stifle his ambition. Ambition can be a good thing — an earnest desire to achieve a level of personal distinction. Oh, it can certainly run amuck. But ambition and achievement frequently go hand in hand.

More recently, I asked another young student the same question: what do you want to be when you grow up? With equal sincerity, he told me he wanted to be "famous." I, of course, asked him famous for what? His answer? "You know, famous."

It'd be easy to moralize here about the impact of today's popular culture — of reality TV and pop icons who've achieved their fame simply by acting outrageously. I'm sure pop culture had some impact on his response — his iPhone was close at hand. But in both cases I'd been talking to children — children who were trying to sort out what they wanted to be.

I talked at length with my friend who sought fame. Do you want to be famous for finding a cure for cancer, I asked, or building great buildings, or creating timeless works of art? I'll admit, I think he wanted throngs of young fans screaming at him on stage. But even at his young age, he clearly understood the point I was making. You could see he wanted to do good things. There was just so much to sort out.

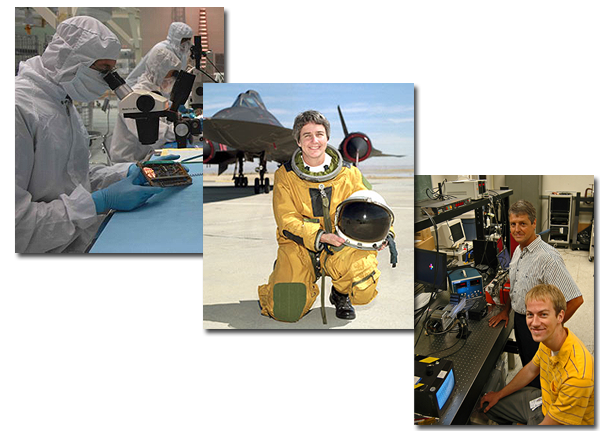

And it made me realize, once again, how important teachers are. Not just the teachers we find in school, but friends, parents, and all adults. Every interaction we have with a child is a chance to shape that child's mind. Not just with facts, but with possibilities. A colleague reminded me that, growing up, she felt limited to one of three professions: secretary, nurse, or school teacher.

Today, the possibilities are boundless for the well educated mind of any race or gender. We live in an ever more complicated world. A world where computers touch every aspect of our lives, from staying informed to driving cars. A world where cultures are intertwined like never before as global business brings us all closer together.

This is the world our children will inherit. If we point them in the right direction — or better yet, point out the many good directions that are available and let them choose — they'll make good decisions. But they're counting on us to show them what's out there.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

The picture of the pope is from Wikimedia Commons. The picture of the woman holding a diploma is from the Connecticut State Department of Education Web site. All other pictures are from Web sites operated by the U.S. government.