Celebrating Human Ingenuity

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a story in two parts. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The woodpecker finch, found in the Galapagos Islands, isn't actually a woodpecker. True woodpeckers peck to loosen bark on a tree, then use their long tongues to search for grubs. Woodpecker finches' tongues are too short for that. So they use a cactus spine to pry grubs from the bark. When the grub can be reached, they set the spine down, consume the grub, then pick the spine up and search for more grubs.

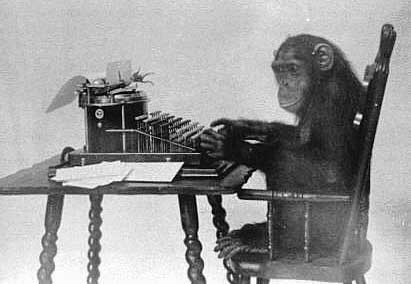

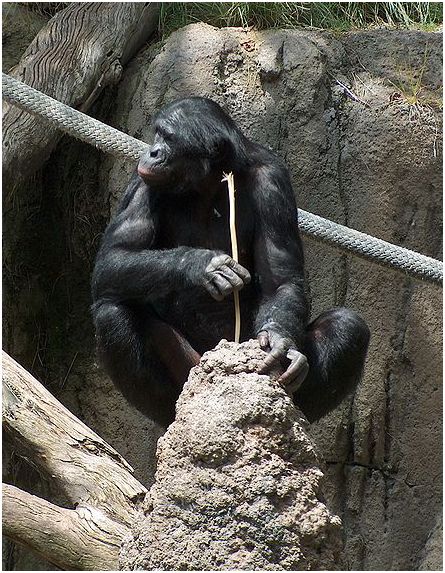

The woodpecker finch is using a tool, and there are many such examples in the animal world. Chimpanzees use twigs to fish for termites. Sea otters use rocks to crack open shellfish while contentedly floating on their backs. Elephants use sticks to scratch an itch.

Animal ingenuity doesn't stop with tools. Chimpanzees have been taught to communicate with sign language. Parrots have an extraordinary ability for precisely recreating sounds. Dolphins teach their children how to protect their noses with sponge when foraging for food. Some border collies have learned to understand hundreds of words. Even the lowly veined octopus has been observed manipulating broken coconut shells to build a home.

There's no denying that animals can be ingenious. And they're ingenious in ways that elude the most complicated machines. Computers can do impressive things, but only because of human instruction.

And this brings us to the second part of our story. Much as I marvel at animal ingenuity, what truly amazes me is human ingenuity. It far, far surpasses that of than any other animal. Think about it. Every day we deal with tasks so complex no animal could hope to accomplish them. Driving to work. Balancing a checkbook. Understanding the evening news. All routine activities.

The story's even more amazing when we consider the less routine. We make involved plans that span our entire lifetimes. We enjoy intricate music. Our doctors fight disease. Our teachers pass down centuries of accumulated knowledge. Our capacity to understand mathematics is almost unimaginable, and our comprehension of the physical universe through the language of mathematics leaves me in awe. Animals can't so much as understand the meaning of the number 100.

Weighed down with bringing home a paycheck or caring for our families, it's easy to forget how remarkable we are. Humans are the most ingenious creatures ever to walk the earth. That doesn't mean we should place ourselves on a pedestal. Quite the opposite. Our capabilities carry with them special responsibilities. But it is worth stopping and celebrating our uniquely human ingenuity.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

H. Coupin and J Lea. The Wonders of Animal Ingenuity. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1910.

L. Kosseff. Untitled. From the Tufts University Web site: http://www.pigeon.psy.tufts.edu/psych26/birds.htm. Accessed January 12, 2010.

The picture of the woodpecker finch is taken from the Tufts University web site: http://www.pigeon.psy.tufts.edu/psych26/images/thefinch.jpg. Accessed January 12, 2010.

The chimpanzee pictures are taken from Wikimedia Commons.