Ships of the Levant

Today, only a picture of a ship. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Shelley Wachsmann's book, Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant is about a seemingly small slice of maritime history. The word Levant describes the ancient Mediterranean world, eastward from Venice. And the slice is really not so small, because those nations turned the Mediterranean, in his words, from a barrier into a thoroughfare. It was a seafaring world.

Yet Wachsmann faces a big problem. For the most part he has only pictures to go on. The actual biodegradable ships of wood and reeds have perished. To know this culture of ships and sea trade he has to study wall paintings and bas reliefs, images on pottery or on coins, fragments of papyrus ...

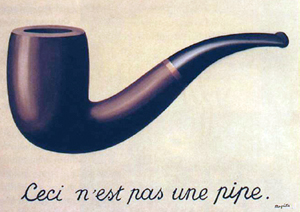

And here lies a curious trap. Wachsmann quotes the artist Magritte who paints a smoker's pipe, then titles his painting, This Is Not a Pipe. Well of course it's not a pipe; it's a picture. A picture is not the real thing and it can deceive us -- something we need to remember in our world of TV, movies, and computer screens.

And here lies a curious trap. Wachsmann quotes the artist Magritte who paints a smoker's pipe, then titles his painting, This Is Not a Pipe. Well of course it's not a pipe; it's a picture. A picture is not the real thing and it can deceive us -- something we need to remember in our world of TV, movies, and computer screens.

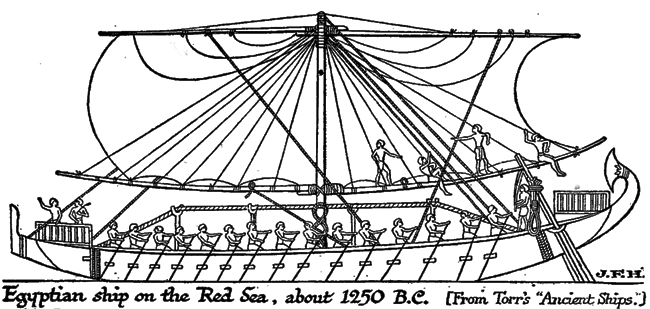

Take the Egyptian pictures. Many are gloriously detailed. They show how ropes are tied off and oars are mounted. Then Wachsmann shows us an ornate picture of a ship leaving and the same ship returning. But: the details differ in the two ships. Which is true? Or is reality some third ship, not shown to us?

So archaeologists compare and sift images. Now and then they find a model -- even a small ship itself -- in a tomb. Shipwrecks tell him something. The ships are gone; but non-biodegradable items remain: clay amphoras and pottery, metal fittings, stone anchors. And the detritus often defines the size and shape of the vessel.

Most of this ancient shipping combined oars and sails, but the pictures leave frustrating questions unanswered. Did they have keels, for example? Keels are needed if a sailing ship is to tack against the wind. Some ships are so nearly fore-aft symmetrical that it's hard to know which end is the prow and which the stern.

Wachsmann turns to seagoing cultures that use such technologies in our own era -- large ocean-going Solomon Island canoes, Chinese dragon boats. Their designs include solutions to many of the same problems the Egyptians or the Minoans faced.

Understanding does emerge from all the fragmentary evidence. Once we digest the unwritten words "This is not a ship" under the delicate images on walls and pots, we begin to hear the creak of planks, smell the salt spray, and feel the wind in our face.

The ships that carried Odysseus about the Aegean take on form and substance. We ride with Cleopatra and Anthony -- see the ship that wrecked and stranded Paul of Tarsus on his voyage to Rome.

But more than that, we learn to question the evidence of our eyes. That's the message I take from Wachsmann's work. We must keep asking questions, even after -- especially after -- we think we've been shown the truth.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

S. Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. (College Station, TX: Texas A&M Univ. Press, 1998).

Called the oldest, largest, best preserved of the funereal ships, this is The Khufu Ship or the Barque Soliare -- Solar Barge -- from a part of the Great Pyramid complex. We have very little in the way of such complete vessels from ancient times.

All images from Wikipedia Commons.