Clara Adams Takes Flight

Today, Clara Adams flies. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The consumer is always the last terribly important link in the evolution of new technology. Consumers shape technology in ways we don't fully see because it takes so many to shake the kinks out of a new machine. But Clara Adams was a standout leader among consumers of the 20th-century's new technology of flight.

She was born Clara Grabau in 1884, to German parents in Cincinnati. She went to Germany to study music in Leipzig. There, her mother lived next door to Count Zeppelin (a connection that caught up with her later.) But first she returned to America where she married wealthy Pennsylvanian George Adams. He was president of a leather tanning company and forty years her senior.

It was in her new role as a wealthy socialite that she turned her energies to the fearless promotion of commercial flight. Our first commercial flights were made in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1914. Clara Adams was right there to buy her five-dollar ticket for the flight to Tampa.

Three years later, she went to San Antonio where Katherine, Marjorie, and Eddie Stinson had set up a flying school. Marjorie gave Adams her second airplane ride, months before we joined WW-I. (When we did, Marjorie went to Canada as a flight instructor and Katherine to France as an ambulance driver.)

After the war, soon-to-be German President Hindenburg (who happened to be her shirttail relative) gave Adams a letter of introduction to Hugo Eckener. Eckener was now head of the Zeppelin Company. She rode in a test flight of a dirigible there.

Not long after, she became first woman to fly the Atlantic as a paying passenger. That was on the Graf Zeppelin. She'd also met Claudius Dornier at the Zeppelin works. Seven years later, she was the first woman to cross the Atlantic as a passenger in an airplane -- Dornier's huge 12-engine flying boat. She was first to fly the Atlantic in the dirigible Hindenburg, first to fly the Pacific in the China Clipper, first to fly America coast to coast in a Boeing Stratoliner. She flew in balloons and she flew in autogiros. She flew 150,000 miles of dangerous maiden flights.

Consumerism really is necessity clad in the clothes of folly. How many of us paid good money for early computer software -- little of which was worth the trouble -- seemingly wasted our time on half-baked inventions. But that trial and error had to be done before we could have a smooth-running computer-served world. Those of us who don't take part simply benefit from the efforts of those who do.

So Clara Adams was there -- highly visible -- championing, writing about, and making speaking tours for, the new flying machines. Dirigibles, autogiros, and flying boats have all faded. The sifting was finished only after such early users put on faces of high optimism and led us through all the radical experiments. Only then could we ever come to our settled routines of coming and going in airplanes that're now as functional and unimpressive as old shoes.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

I am grateful to Anne Ribble and Marjorie deHartog who prodded me to do an episode on this remarkable woman.

See also the Airships.net account of Adams' life.

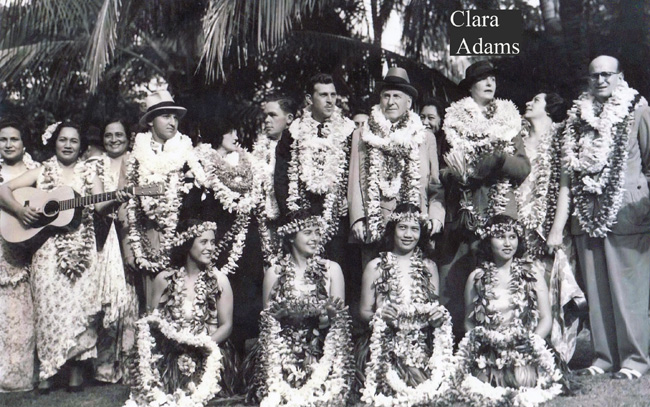

Clara Adams in a celebration of the maiden flight of the Hawaii Clipper, 1936. To put this in perspective, she was crossing the Pacific as passenger a scant nine years after Lindbergh flew the Atlantic. Image courtesy of the archives of the government of Hawaii.