The Dornier X

Today, Dornier's flying palace. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Airplanes are such lovely machines -- glorious as birds, in their diversity. The smallest piloted airplane, the Bumblebee II, flew in 1988. This tiny biplane, with its five-and-a-half-foot wingspan, was built by Robert Starr of Phoenix, Arizona. Starr flew it several times before he crashed and was seriously hurt.

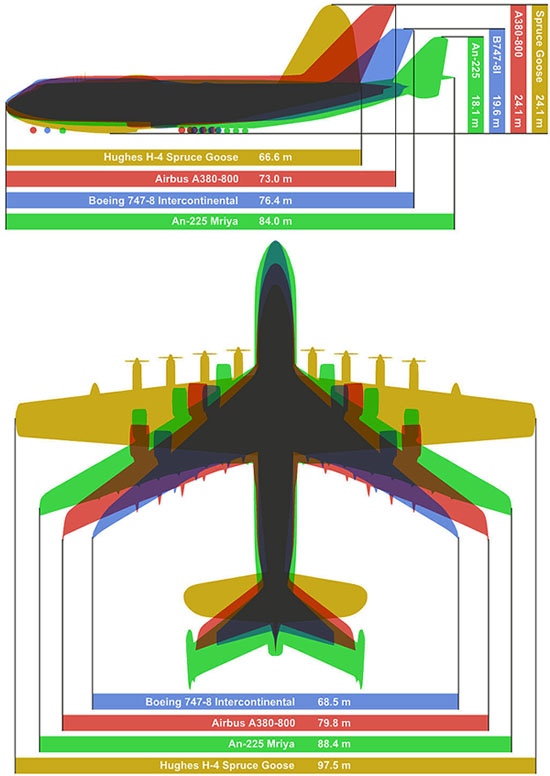

Several planes vie for the crown of largest-ever-flown. It depends on whether we look at wingspan, weight, or some other figure. We have yet to exceed the 319-foot wingspan of Howard Hughes' Spruce Goose, or the 650-ton takeoff weight of the \ Airbus 380 -- capable of carrying 853 passengers.

That said, here's a historic extreme airplane for you: the 1929 Dornier X. Germany was under the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty which forbade her from building powered airplanes. The engineer, Claudius Dornier, had honed his skills working for Count von Zeppelin on dirigible design. When he turned to heavier-than-air seaplanes, he set up shop on the Swiss side of Lake Constance where he wouldn't violate the Treaty. Now he'd finished his Dornier X; and what an airplane it was!

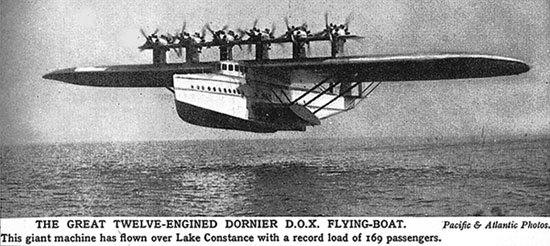

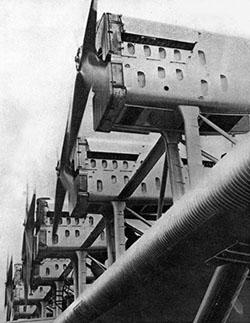

Its takeoff weight was over sixty tons and it was powered by twelve six-hundred-horsepower engines. They were mounted in six pods above the airplane's 157-foot wing. Six engines pulled the airplane forward; and six more faced backward, pushing it. It was far and away the largest airplane up 'til then. designed to carry seventy passengers in sumptuous comfort. Dornier called it the X because it heralded an unknown future.

Its takeoff weight was over sixty tons and it was powered by twelve six-hundred-horsepower engines. They were mounted in six pods above the airplane's 157-foot wing. Six engines pulled the airplane forward; and six more faced backward, pushing it. It was far and away the largest airplane up 'til then. designed to carry seventy passengers in sumptuous comfort. Dornier called it the X because it heralded an unknown future.

The X made a demonstration run over Lake Constance in October, 1929. During the forty-minute flight, it carried, not seventy, but 169, people -- employees, journalists, stowaways, and a ten-man crew. That record wouldn't be bested until the mid-'40s.

A year later, The Dornier X set out on another demonstration run. This time it would fly the Atlantic (three years after Lindbergh). The convoluted route included stops throughout Europe, then from Portugal to West Africa and across the Atlantic to stops in South America. Finally it flew to New York by way of Miami.

Of course the flight exposed weaknesses. The engines ate too much fuel; a fire in Lisbon grounded it for six weeks. The ten-month Odyssey actually made it clear that this plane would never provide the regular transoceanic service the public wanted. At the same time, I can hardly call this grand gesture a failure.

I can only dream of flying a long flight in this aerial hotel with its private sleeping quarters, its central salon carpeted in Oriental rugs, plush furniture -- of eating freshly prepared food in its dining room. Airplanes are indeed as lovely as birds in their diversity. And I especially grieve that no Dornier X survives to display its brilliant plumage in our plain utilitarian age of aerial transport.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

O. E. Allen and Time-Life Editors, The Airline Builders. (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1981): pp. 44-49.

For more on the Dornier X, see this Wikipedia site .

This site on early German flying boats provides excellent photos of the Dornier X along with several of Dornier's other seaplane designs.

Images above from The Wonder-Book of Aircraft. (H. Golding, ed.) (London: Ward, Lock & Co., Ltd. 1920 and subsequent eds.). Images below courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. The bottom image compares very large airplanes as of 2008.