Hippodamus of Miletus

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a grid for the ages. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

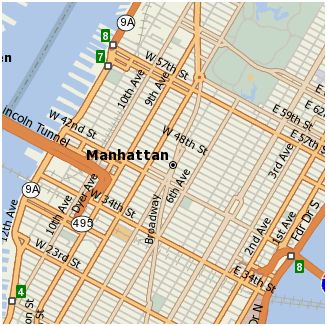

Manhattan's street network is a grid of perpendicular lines. Broadway cuts through at an odd angle, and things aren't perfect along the waterfront. But overall, the borough is made up of nice, orderly, rectangular blocks. Which leads us to ask, why? For urban planners, one name in particular comes to mind: Hippodamus of Miletus.

Hippodamus lived in the fifth century B.C. We learn of him in Aristotle's important work, Politics. In Greek, "politics" literally means "things concerning the polis" or "city-state," not just the workings of government. So urban planning fits right in.

Hippodamus lived in the fifth century B.C. We learn of him in Aristotle's important work, Politics. In Greek, "politics" literally means "things concerning the polis" or "city-state," not just the workings of government. So urban planning fits right in.

From Aristotle we learn that Hippodamus was "… a strange man, whose fondness for [personal recognition] led him into … eccentricity …" Hippodamus wouldn't be the first or last creative person to be described as "eccentric."

Aristotle also summarizes Hippodamus's plans for the ideal city-state: ten-thousand governing citizens divided into artisans, farmers, and soldiers. Land divided into three parts: public, private, and sacred. According to Aristotle, Hippodamus was "the first [non-statesman] who made inquiries about the best form of government."

Aristotle took issue with most of Hippodamus's ideas about government. But he praised Hippodamus for his attention to the urban environment of an ideal city-state. Aristotle went so far as to say that Hippodamus "invented the art of planning cities."

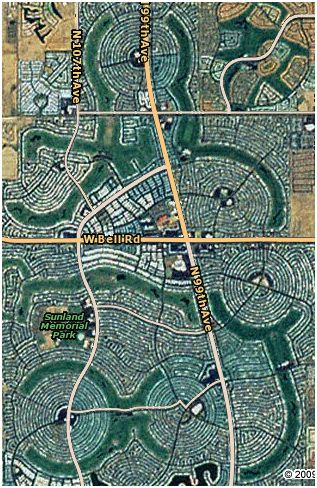

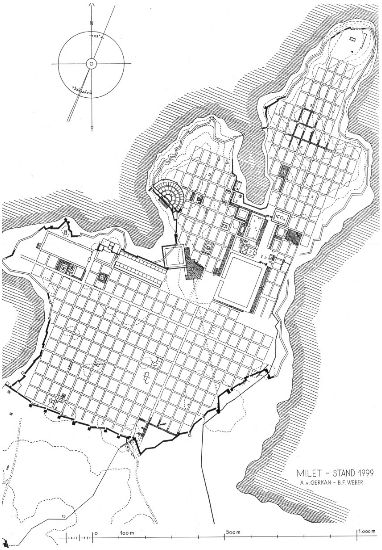

Hippodamus had his hand in building ancient Miletus and Piraeus — two port cities specially designed around rectangular grids. Grids weren't the norm. And this led early scholars to conclude that Hippodamus earned his reputation as inventor of city planning by devising street grids. Manhattan's layout is a modern example of what urban planners call the Hippodamian plan.

But Hippodamus didn't just lay out perpendicular lines in the sand. Evidence of geometric road networks predates his efforts by at least a century. Hippodamus went further. He envisioned the city as more than a place to live and work. He viewed it as something "democratic, dignified, and graceful." And his designs reflected this philosophy without losing site of practicality.

This was Hippodamus greatest achievement: recognizing that urban planning was about more than engineering a functional city. It was about creating an environment that expressed and nurtured the ideals of its citizens.

A laudable goal. And one that the best urban planners and architects strive toward to this day.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Special thanks to Jean Krchnak, curator of the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture at the University of Houston, for bringing the story of Hippodamus to my attention.

Hippodamos. The Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects. New York: Free Press, Collier MacMillan, 1982.

Aristotle. Politics. Translation taken from the MIT classics web site https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.html. Accessed September 21, 2009.

The picture of ancient Miletus is widely available and considered public domain. The maps of Manhattan and Sun City are from MapQuest.