Sturzkampfflugzeug

Today, a troubled machine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I talk about many different airplanes in this series. But I've avoided one -- the World War II Junkers Ju-87, the Stuka dive bomber. The Stuka has long been a trouble to my mind. Here was a basic instrument of NAZI Blitzkrieg -- war as lightning attack, war as shock and awe. The Stuka first saw service in the Spanish Civil War. Then it was used against Polish civilians in 1939. Early on, it was fitted with a wind-driven siren that uttered a banshee scream at maximum dive speed. The NAZIs called it Jericho's Trumpet, and used it to terrify people below. Of course that soon lost its novelty, while it kept reducing airspeeds by 15 miles-an-hour. They abandoned the siren.

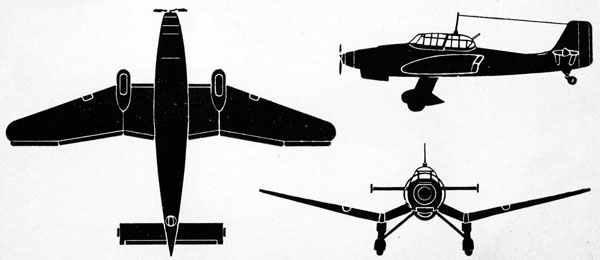

"Sturzkampfflugzeug" or Stuka, Junkers, Ju 87

But, beyond the Stuka's horrific use, I'm troubled by two design elements: Airplanes were in the midst of a leap forward; Stukas were yesterday's news as soon as they flew. They also set up a strange contradiction between beauty and ugliness.

Germany had bought four primitive Curtiss dive bombers in the early 1930s. Those were still old biplanes, but the Germans knew they were the warpla ne of the future. A young designer, Hermann Pohlmann, responded with a series of attempts to build a competitor. By 1937, he'd given the Stuka its basic form.

ne of the future. A young designer, Hermann Pohlmann, responded with a series of attempts to build a competitor. By 1937, he'd given the Stuka its basic form.

Pohlmann was committed to the art deco ideal of simplicity and angularity. The Stuka had both: It was a low winged monoplane with a fixed landing gear. Retractable gear would've violated its basic simplicity. Still, teardrop covers streamlined the wheels. An inverted gull wing dipped down from the fuselage to where the landing gear attached, then rose again. The wings and tail were angular, while a large nose spinner began a smooth line from nose to tail. The result was truly Darth Vadar-ish. People today generally call it ugly. But I find its functional lines compelling. Of course, I also think grackles are beautiful birds.

The Stuka was something you might expect to see in the 1930s comic strip Smilin' Jack. It had that sort of razzle-dazzle, but it was slow and vulnerable. As long as the Wehrmacht attacked defenseless enemies, the Stuka was devastatingly effective. Send a typical WW-II fighter up against it and it was doomed.

That's why the Stuka fell from grace during the Battle of Britain. It became a tool for low-altitude troop support in theaters where there was little allied air presence. And it made a good training plane. Nevertheless, 6500 were made while engineers tried to save it with every kind of modification and improvement.

Here in America, we studied the Stuka just as Germany had studied our old Curtiss biplane. We responded with the similar, but more advanced, Vultee Vengeance dive bomber. And, unless you too are old, you may never've heard of the Stuka. But, for a season, this throwback was the very icon of all that threatened us. And it was also an echo of 1930s art -- this angular expressionist woodcut with its fragments of art deco, and just a hint of modern streamlining.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the Wikipedia article about the Junkers Ju 87. See also this site. (Stuka, by the way is shorthand for the full name Sturzkampfflugzeug or drop-down-fight-airplane.)

M. Griehl, Junkers Ju 87, Stuka. (Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Pub. Co., 2001.)

Thanks to Jean Krchnak, UH Art and Architecture slide librarian, for her counsel. Stuka images above are from WW-II American airplane spotters manuals. Grackle photo by J. Lienhard. Stuka images below are courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Click here to see Stukas in flight.

The dark side: Above, Stukas over Poland in 1939.

Below, a 1943 German stamp celebrating the Stuka.