Broken Brushes

Today, broken brushes. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

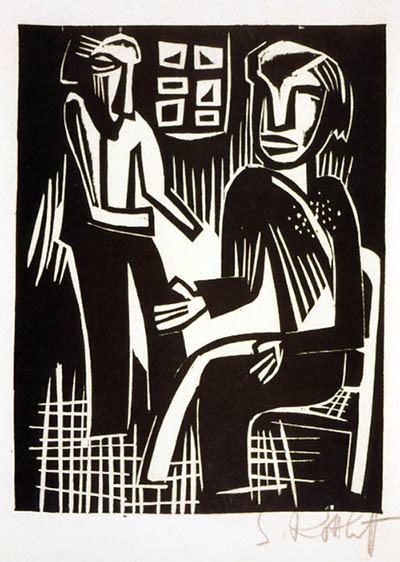

I've been reading a fascinating book, Broken Brushes -- about German expressionist art from the late 19th century until Hitler put a stop to it the late 1930s. Well, put a stop to it is not entirely accurate. For there it is today, still insisting we come to terms with the human dilemma.

These mostly-monochrome prints and drawings are from Gus Kopriva's large collection. Kopriva, a civil engineer, was drawn to art during his engineering studies. You catch his structural sense of purpose when he says that he and his wife were taken by the art's "situational imagery," which addressed "major social, economic and political matters of their time."

We've all seen examples of this art, but here a full and intense view is packed between two covers. German expressionism arose after a period of settled complacency following the Franco-Prussian War. By the early 1900s, a number of rebel artists were exaggerating reality with fast slashing pen or brush strokes. The formal portrait artists around them were properly horrified.

These artists gained footing just as another war began -- a war that would have a major influence upon them. Since they were largely young men, many died in WW-I. And those who came back were sickened by what they'd seen. They'd gone off hoping to fill their sketchbooks, and they did -- but with expressions of overwhelming horror. The post-war world may've been post-expressionist; but these artists continued, and they took up the pacifist cause.

Alas, another German artist, a mediocre one with no tolerance for expressionism, was gaining political power. Adolph Hitler's paintings were workmanlike city and landscape scenes. He loathed the expressionists and all they represented.

Historian Irene Guenther's article in Kopriva's book describes the purges in chilling detail. They reached an apogee in 1937 when the government mounted an exhibit of so-called Degenerate Art. The NAZIs tried to demonstrate how low art had sunk. That same year, Hitler wrote about the state of art in Germany. He said,

From now on we [will] wage a merciless war of destruction against the last remaining elements of cultural disintegration. [Then he adds that] some people's eyes fail to show them things as they really are.

Kopriva derives his title Broken Brushes from the subsequent NAZI destruction of art an artists alike. Yet Hitler's Germany needed money, so it didn't destroy everything. Rather, it confiscated much of the art to sell for profit.

But Hitler's words about reality linger as I look at the pictures. By distorting reality, these artists find a larger reality. Their slight twists of reality reveal what lies inside the picture our eyes show us. Those expressionists gave us a perfect means for cutting away a corrupt veneer. Small wonder they affect us in such stunning (and such disturbing) ways when we see their work a century later.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. Kopriva, Broken Brushes, German Art from the Kaiser to Hitler.(Houston: Redbud Gallery, 2006.) This includes two essays: "Impressions of Anxiety and Ecstasy: The German Print from 1872 to 1919" by Jim Edwards; and "Modern German Art and Its Demise: 1914-1945" by Irene Guenther.

My thanks to Gus Kopriva, Redbud Gallery, 303 11th St. Houston, TX 77008, for his counsel and for permission to display the images below from Broken Brushes:

See also the Wikipedia article on the German expressionists.

Das Paar (The Pair) by Paul Kleinschmidt

Gesprach vom Tod (Conversation from the Dead) by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

Alte mit Spaten (Elder with a Spade) by Gerhard Marcks

Hunger by Käthe Kollwitz