Texas Germans

Today, Texas auf Deutsch. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

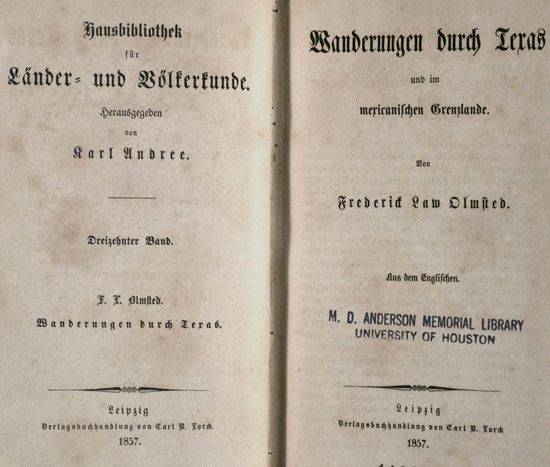

I talked in a previous episode about Frederick Law Olmsted's travels throughout Texas in the 1850s. Olmsted was the founding father of American landscape architecture, but his travel narratives of the south were an important contribution to the debate on slavery, which raged before the Civil War. To my surprise, I found a German edition of his Texas travelogue published in Leipzig in 1857. That's the very same year as the first American edition. Olmsted's accounts were also published in London because the British followed the American slavery debate with intense interest. But why was a German edition so quick to come out?

Olmsted camping in Texas with his brother. From A Journey Through Texas (1857)

The answer is, because Texas in the 1850s was a very German place, and Germans loved to read about it. A group of German noblemen had organized immigration to Texas in the 1840s, initially with catastrophic results. The death toll among the first wave of settlers was appalling, due to poor timing and provisioning, and unrealistic expectations. But the Germans quickly recovered and built thriving centers at New Braunfels and Fredericksburg—both named for noblemen who were a part of the immigration scheme.

According to Olmsted's figures, Germans comprised nearly a third of the population in towns like San Antonio; they were the dominant group in many counties in the Hill Country. But numbers weren't the reason for Olmsted's interest in the Germans. The thriving German communities were his standing argument against the slave-plantation economy that was encroaching upon the Texas frontier. They were the shining example of what free labor and devotion to democratic ideals could accomplish in the new land.

Many of the Germans Olmsted encountered were former revolutionaries—but not from the Texas Revolution. They were refugees from the great European Revolutions of 1848; they'd fled Europe after the forces of reaction set in. Some of them were highly educated, yet forced by circumstances to build a life in the rugged conditions of the frontier. Olmsted writes about the "bizarre contrasts" of these settlers, "You are welcomed by a figure in a blue flannel shirt and a pendant beard, quoting Tacitus, having in one hand a long pipe, in the other a butcher's knife;…coffee in tin cups upon Dresden saucers; barrels for seats, to hear a Beethoven's symphony on the grand piano…a book-case half filled with classics, half with sweet potatoes."

Title Page of Olmsted's Wanderungen Durch Texas und im Mexicanishen Grenzlande, 1857. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries

Olmsted was greatly impressed by these principled people who labored under harsh conditions. They remained devoted to the high ideals they'd fought for in Europe, even though they'd lost all their wealth and position. For a time, he even worked together with German radicals to promote the idea of creating a free state in West Texas to check the tide of slaveholding in the new territories. This didn't happen, of course; but it's thrilling to imagine such startling ideas tossed about in the Wild West. In 1857, Germans in Europe were still only dreaming of a democratic nation. But German Texans were already part of a great and dangerous experiment in radical freedom.

I'm Richard Armstrong, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Wanderungen durch Texas und im mexicanischen Grenzlande. Published in the series Hausbibliothek für Länder- und Völkerkunde, vol. 13, edited by Karl Andree. Leipzig, Carl B. Lorck, 1857.

Karl Andree (1808-1875) was a German nationalist with an intense passion for geography, "scientific ethnology," and especially for North America—hence his eagerness to publish Olmsted's book. This German edition is historically interesting in that he sustains throughout an argument with Olmsted about the future development of non-white races, in which Andree is engaging in pre-Darwinian racism (he sees different ethnic groups as separate species with fixed natural characters). He dismisses Olmsted as a naïve abolitionist and "philanthropist."

One of the radicals Olmsted befriended was Adolf Douai, publisher of the anti-slavery newspaper The San Antonio Zeitung. He later was forced to move east, where he remained politically active.

Also see Episode 2497.