Forms of Nature

Today, another look at form and function. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

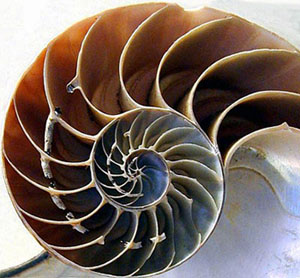

NOVA did a fine program back in 1985: The Shape of Things. It explained why the chambered nautilus displays a pure spiral of Archimedes and why rivers meander. It showed a hundred ways that nature puts spheres, hexagons, and helixes to use. I especially liked the part about tree branches.

NOVA did a fine program back in 1985: The Shape of Things. It explained why the chambered nautilus displays a pure spiral of Archimedes and why rivers meander. It showed a hundred ways that nature puts spheres, hexagons, and helixes to use. I especially liked the part about tree branches.

A tree must keep its leaves -- its solar collector -- evenly spaced. That can be done in many ways: a small plant might array each leaf on its stem so they all radiate from a central hub. But a tree has far too many leaves for that. How to hold them all out to the sun without collapsing under its own weight? The tree minimizes its weight by subdividing its stem -- by dividing in two, over and over, until each leaf rides at the end of a mere twig.

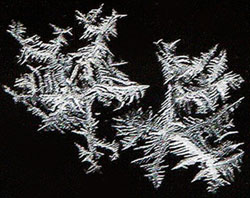

Nature has all kinds of tricks up her sleeve. The shapes of snowflakes, feathers, wind ridges on sand dunes -- they all achieve her ends with remarkable grace and economy.

Nature has all kinds of tricks up her sleeve. The shapes of snowflakes, feathers, wind ridges on sand dunes -- they all achieve her ends with remarkable grace and economy.

The NOVA program ended by panning across a bucolic vista until it opened into a view of a city. Just when we'd been hypnotized by splash patterns and bird skeletons -- by waves and spider webs -- we suddenly saw the harsh lines of the human hand laid across nature's order.

But wait a minute! A city is also a part of nature. You and I are elements of nature as we build our city. The city seems to intrude on the simpler rhythms of form outside it only until we assume a new set of eyes. Imagine we're a disembodied intelligence from another galaxy. We've never seen Earth and never seen a human. Figuring out the purpose of a house, a highway, or a cathedral from that vantage point might well be harder than understanding the shape of a tree. We are a complex species and the organic forms of our cities evolve in byzantine ways.

So we need to see our city in the framework of its purpose. Like the chambered nautilus it is beautiful within that framework. It fulfills our complex, diverse, and subtle needs in strange and unexpected ways. That's why I like Houston so much. Its form shifts on every street. Some unopened oyster, some hidden pearl, lurks in every byway -- bayous and skyscrapers, stadiums and theatres, fast food and fine food, electronics and antiques. Not every element serves every individual, but as a unit it serves us all.

We are, after all, homo technologicus -- a species which, more than any other, survives only with the help of an exoskeleton. That exoskeleton is a huge system of sustaining technologies. Few forms in nature have to fulfill such complex functions as a city does. It's facile to see beauty in a sea shell.

But step back, instead, and look at our sprawling city. Let its functions and its stunning range of purpose come into focus. As they do, the city becomes a natural phenomenon complex and lovely -- as a sunrise or a redwood tree.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode No. 275. All photos by J. Lienhard