Electric Hope in 1889

Today, we "discover" electricity. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

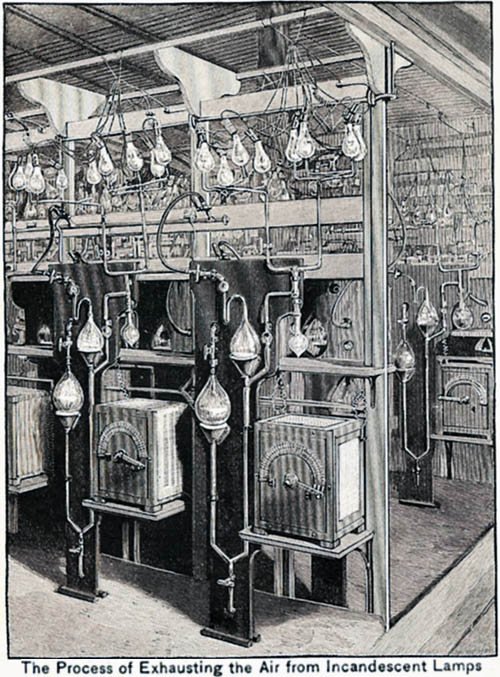

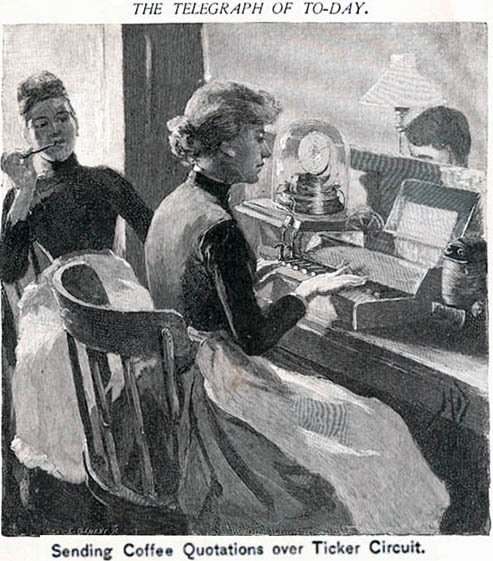

America "discovered" electricity in the 1880s. An 1889 volume of Scribners Magazine makes that very clear. The telegraph had been around for decades by then. Otherwise, our electric world was just coming to life. Commercial telephones, less than a decade old, were still feeling their way. Electric lighting systems were brand new -- arc lamps, and then light bulbs. Electric motors had been on the market for sixteen years and were now finding service in trolley cars and electric elevators.

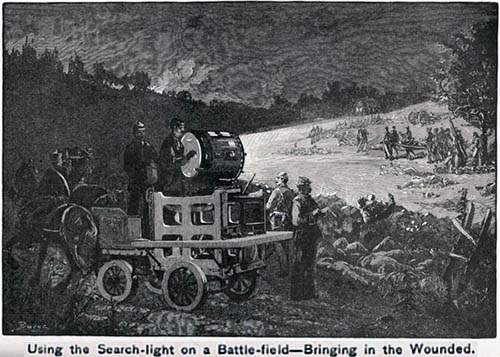

We were drunk on the elixir of electricity in 1889. Scribners brims with articles on this new magic: articles about the present state of telegraphy, electric lighting, electricity in warfare, electricity as it relates to the human body. An aura of hope underlies it all. For it's clear we've seen only the beginning.

Still, we face the age-old problem of reading the promises of new technology. We're always slightly off, if we aren't massively wrong. We expected observation balloons to communicate through dangling telegraph wires. Balloons used semaphore signals during the Civil War. By WW-I, they would use telephones and even radio.

An article correctly predicts that electric motors will be used to drive torpedoes. But they also make a big point of ships using new electric searchlights to spot other ships. Of course the range of a searchlight is hopelessly limited, and it'd be another fifty years before radar and sonar could take up that task.

The creepiest article describes effects of electricity on our bodies. It begins with Edison's proposal to do humane executions with alternating current. Four years later, axe murderer William Kemmler died in the first electric chair. A thousand volts left him still breathing. So they hit him with two thousand, and left the odor of burnt flesh hovering over his thoroughly dead body.

But that was later. Now the article says a lot about electric resistance of human flesh and fluids. We learn that the anesthetic cocaine immediately desensitizes soft tissue. If the pain lies beneath skin, cocaine has no effect. But if we let electricity flow from a cocaine-soaked electrode, into the body, the cocaine will flow with it. It'll pass through skin and relieve pain.

Can electric probes reveal bullets in human bodies? That'd been tried unsuccessfully five years earlier when President Garfield lay dying -- shot by an assassin. But it was generally assumed that metal bedsprings had thrown the probes off.

Well, this really was a brave new world, and this article stresses how strongly electricity can affect our bodies. Now our task was to identify effects that would be beneficial.

Electricity was still a mysterious unknown, but an unknown poised to do our bidding. Hope is what this is all about -- hope that we'd seen only the tip of the lightning rod of change. And of course that could not have been more true in 1889.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This episode refers to several of the articles in the July through December, 1889, issue of Scribner's Magazine, Volume 6. In addition to four major articles that directly address electricity, others bring it in tangentially. All illustrations from this source.