Napoleon's Aerial Crown

Today, Napoleon's aerial crown. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

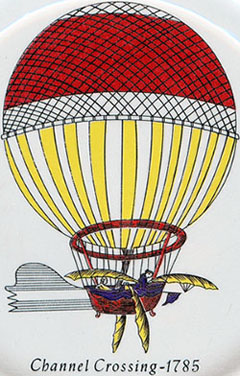

The French flew both the first manned hot-air balloons, and the first hydrogen balloons, in 1783. The public was immediately enchanted. Within two years a balloon had crossed the English Channel. Balloon images appeared on dinnerware, chandeliers, wall hangings -- furniture embroidery and balloon-framed clocks. Lovely floating globes, real and imagined, were suddenly everywhere. The mania continued right through the French Revolution.

The French flew both the first manned hot-air balloons, and the first hydrogen balloons, in 1783. The public was immediately enchanted. Within two years a balloon had crossed the English Channel. Balloon images appeared on dinnerware, chandeliers, wall hangings -- furniture embroidery and balloon-framed clocks. Lovely floating globes, real and imagined, were suddenly everywhere. The mania continued right through the French Revolution.

After the very first flight, Ben Franklin suggested that balloons might carry invading armies. Balloons were still on people's minds when the new Revolutionary Army found itself fighting Dutch and Austrian troops near the Belgian border. On June 2, 1794, that became the balloon's military proving ground. The Army sent one several hundred feet up on a tether to locate enemy artillery.

Yet here two forces collided: Balloon mania and military conservatism. Chemist Jean Coutelle had not only built a military balloon, he'd also set up its support infrastructure. For a while, he and his corps of aeronauts successfully spotted the enemy, relayed signals, and distributed propaganda.

Yet here two forces collided: Balloon mania and military conservatism. Chemist Jean Coutelle had not only built a military balloon, he'd also set up its support infrastructure. For a while, he and his corps of aeronauts successfully spotted the enemy, relayed signals, and distributed propaganda.

At first, the enemy regarded aerial spying as a breach in the etiquette of war. Then they improvised new anti-aircraft tactics. They tried to modify their artillery so it could bring the balloon down. Ballooning simultaneously became dangerous and glamorous. However too much was going on. The war was short-lived. And, when Napoleon came to power, young as he was he brought with him an old-world conservatism in matters of war and its conduct.

He did authorize a small balloon factory and school. And he took a balloon with him on his ill-fated Egypt campaign. But he didn't get around to taking the balloon off the ship before the British sank it in the Battle of the Nile.

Soon after, Napoleon returned to take control of France in a coup. And he shut down the balloon school. He chose to conduct more conventional warfare. He might've been convinced later on; but then the strangest thing happened: Napoleon decided he should be crowned emperor of France in 1804. So he hired French Balloon pioneer Andre Garnerin to build a huge unmanned balloon for the event. It was decorated with a great crown of blazing lights.

The balloon came down two days later after making a remarkable journey all the way to Rome. There it landed on lake Bracciano, but only after the crown had snagged on the tomb of Nero. It broke off and, suddenly, Napoleon's crown rested upon one of the worst emperors history had ever known. Napoleon was not amused.

He fired Garnerin and never again used a military balloon. Not until our Civil War, sixty years later, did balloons again find a role in war. And all because Napoleon was presented with a soul-wrenching omen just as his megalomania reached its apogee.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

D. D. Jackson, The Aeronauts. (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1981): "An Unlikely Recruit for War." pp. 74-107.

Jean Coutelle image courtesy of Wikipedia; balloon images from JHL's old French dessert plates.