The Great Balloon Disaster

Today, first to fly, first to die. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Balloon mania swept France after Jean-François de Rozier piloted the Montgolfier brother's first balloon in 1783. The next balloon-maker, Alexandre Charles, thought he was copying the Montgolfiers when he filled his early experimental balloons with hydrogen. He didn't realize they'd simply used hot air. Now ballooning would become a contest between hydrogen and hot air.

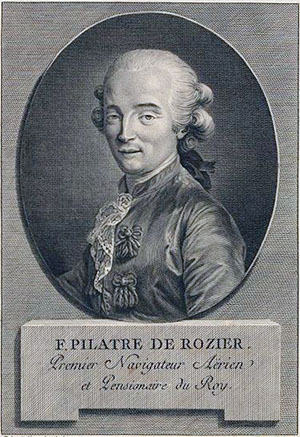

Whichever gas bore them aloft, balloons now claimed the sky. After flying the Montgolfiers' balloon, Rozier meant to show the world what balloons could do. His first goal was flying the English Channel from England to France, but he was immediately scooped by another French aeronaut, Charles Blanchard.

Rozier had to move fast to top that, so he announced he would fly the Channel from France to England, facing far less favorable winds. He'd have to be able to stay aloft much longer.

Rozier had to move fast to top that, so he announced he would fly the Channel from France to England, facing far less favorable winds. He'd have to be able to stay aloft much longer.

Now consider the problem of altitude control: A Hydrogen balloon must release sand to rise, or release hydrogen to go down. Once the hydrogen is spent, the balloon can only sink. A hot air balloon has to be larger since hot air is not as light as hydrogen. We control a hot air balloon's altitude by alternately heating the air in the gas bag or letting it cool. To travel great distances, that took increasingly heavy loads of fuel.

Rozier had a solution: He built a double balloon. A hydrogen-filled bag wasn't quite large enough to lift the balloon off the ground. A second hot air bag would get the balloon into the air. He'd control the altitude by heating the smaller air bag, and that would take a lot less fuel. Rozier's plan was really clever.

But he knew it was also tricky. As the day approached, Rozier became more and more fearful. He made out his will. He insisted that his copilot, the balloon's owner, do so as well. At the last minute, their young patron, the Marquis de Maisonfort, offered the owner two hundred gold louis's to let him fly in his place.

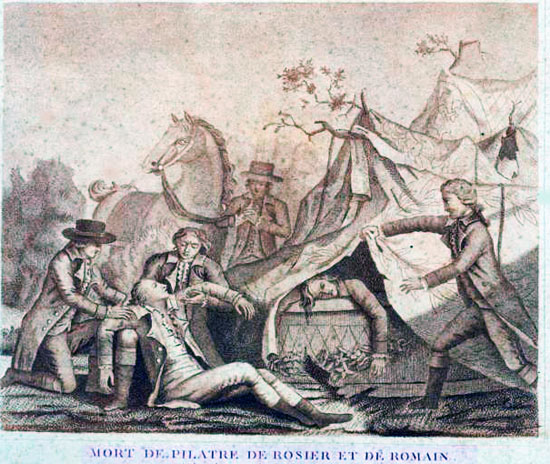

Rozier was appalled. He barely managed to talk the Marguis out of going. Then, at 7:12 that morning, a cannon blast announced the two flyers' ascent as they rose into the grey sky. Thirty-three minutes later, observers saw a tongue of flame four miles away. Twenty seconds later, as the balloon's remnants fluttered \ back toward Earth, a muffled Whump reached their ears.

The balloon had been blown more west than north and never quite made it to the Channel. The watching crowd reached it to find Rozier already dead on the shoreline rocks, and the owner breathing his last. The fire had most likely ignited the hydrogen bag. When the hydrogen burned off, very little buoyancy remained in the hot air bag.

So that's how Rozier, first aeronaut to fly, also became first to die. The sport of ballooning now had to now sober up and settle into the methodical engineering needed to make it feasible. It'd taken a mere two years for ballooning to reach its childhood's end.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

E. Hodgins and F. A. Magoun, Sky High: the Story of Aviation. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1935): Ch. V, "First Disaster".

See also, the Wikipedia articles on Rozier and on the history of ballooning, and the following Engines episodes: 1351, 1545, 1604, 2116,and 2192.

Library of Congress images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Artist's impression of the death of Romain and his copilot, Pierre Romain