Napoleon and Iron

Today, Napoleon builds iron monuments. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Two years before he imposed a military dictatorship on France, Napoleon was the twenty-eight-year-old head of the French army. That year, 1797, he was made a member of the Scientific Division of the Institute of France. That's right! Napoleon was honored for contributions to science, and it was more than a political sop.

The young Napoleon was an important supporter of science and engineering. His support for the new École Polytechnique was crucial. The École soon became the world's leading school of engineering science. A year later, he made his Egyptian campaign into a scientific mission as much as a military one. It was during a military stalemate in Egypt that one of the archaeologists he'd brought along discovered the Rosetta Stone.

But Napoleon's support for the applied sciences soon got mixed up with a fixation on architectural monuments. In 1804, the same year he allowed himself to be crowned emperor, he wrote, "Men are only as large as the monuments they leave." Historian Frances Steiner tells how Napoleon dreamt of melting cannon into heroic iron structures to celebrate battles won. He was still interested in engineering, but that interest had turned to his own glory.

The snag in Napoleon's dream of immortalization in iron was that working with iron takes expertise. The British had mastered ironwork, but France lagged far behind. English iron was expensive, and French iron was inferior. France was still smelting iron with charcoal instead of coke. Her engineers hadn't learned the subtleties of building with iron. Napoleon's new breed of French engineers was eager and surprisingly well prepared to take up the challenge. But French architects were consummate artists in granite. They wanted nothing to do with iron.

During Napoleon's reign as emperor his engineers and architects did execute some major works in iron. They built bridges with varying success. Once they got the hang of it, they built a 160-foot arch over the Seine River and named it after the Battle of Austerlitz. The toughest job was using iron to replace a 130-foot dome over a circular grain exchange, the halle aux blés. That was finished just two years before Waterloo at seven times the original cost estimate.

France did not, by any means, catch up with England during Napoleon's reign. She had too far to go. France eventually produced the Eiffel Tower and the structural skeleton for the Statue of Liberty using iron, but that was seventy years after Napoleon.

When all's said and done, Napoleon probably did start France on its way to iron construction. But what he gave to technology was something else entirely, and it never would've sprung from a craving for monuments. It was the young idealistic Napoleon who laid a foundation for modern education in applied science.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Steiner, F. H., Building with Iron: A Napoleonic Controversy. Technology and Culture, Vol. 22, No. 4, October 1981, pp. 700-724.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 77.

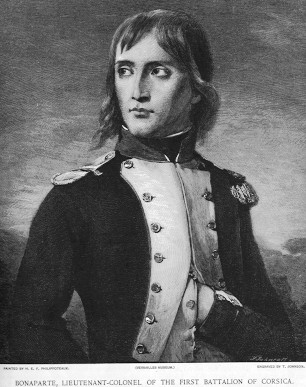

The young Napoleon Bonaparte

From the January 1895 Century Magazine