A Too-Old Photo

Today, we look for the first photo. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We usually credit the first photo to the French engraver, Niepce. Around 1826 he made a photo from his window. It took an eight-hour exposure of his bitumen-covered pewter plate -- hardly a snapshot. But people had wanted to record images automatically, long before that. Camera obscuras were already cameras without film. Artists were using them to cast real scenes on surfaces where they could be traced. Camera obscuras fairly clamored for film of some sort.

Another idea was also afoot: capturing an image by placing a complex object on some sort of chemically treated surface, and letting the sun expose it. We know that Josiah Wedgwood experimented with such processes around the turn of the 19th century. He laid leaves on paper coated with a silver nitrate solution.

Wedgwood and James Watt were friends, members of a scientific seminar that met every four weeks when a full moon illuminated the roads to their meetings. (They called themselves the Lunar Society.) So Watt wrote that he would try similar experiments. Did he? We don't know. Sir Humphrey Davy wrote a paper about the idea in 1802: An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass and Making Profiles by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver.

Something surely came of all this, no? Well, Wedgwood spoke only of his inability to preserve the images he got. In the end we had no images to show for all this work. We've long been frustrated by the lack of any corpus delicti.

Yet we know such images can be preserved. After 1834, another experimenter, Henry Fox Talbot, figured out how fix a silver nitrate image. If he could do it, might it not've been done by someone else earlier. That possibility recently opened up when Sotheby's auction house heard from a person with an old photo image of a leaf. It was the color of rust -- on paper.

It'd turned up along with others in the papers of one Henry Bright. The problem is, this particular Henry Bright lived back in Wedgewood's time. He was part of a technologically savvy family in Bristol. He'd gone to school with family members of the same people who were doing these solar exposure experiments.

Needless to say this has caused a good lot of fuss in the art auction world. But, more important, it once more turns back time in our history books. This image clearly came out of the circle of late 18th-century technologists who were busy rebuilding Britain as they led its Industrial Revolution. Who made the picture -- Wedgwood, Bright, Watt, Davy -- we don't know and we might never know.

But once more, as we turn the furrows of the past, the past retreats. The more we know, the older all of our antecedents become. There was always someone earlier than we thought -- steam engines before Watt, light bulbs before Edison. Now we have photos before Niepce. The closer we look, it seems, the older all of our useful technology becomes.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

R. Kennedy, An Image Is a Mystery for Photo Detectives. New York Times: The Arts, Thursday, April 17, 2008, pp. B1 and B5. (On line HERE.)

What the paper sees of the sun through a leaf (photo by JHL).

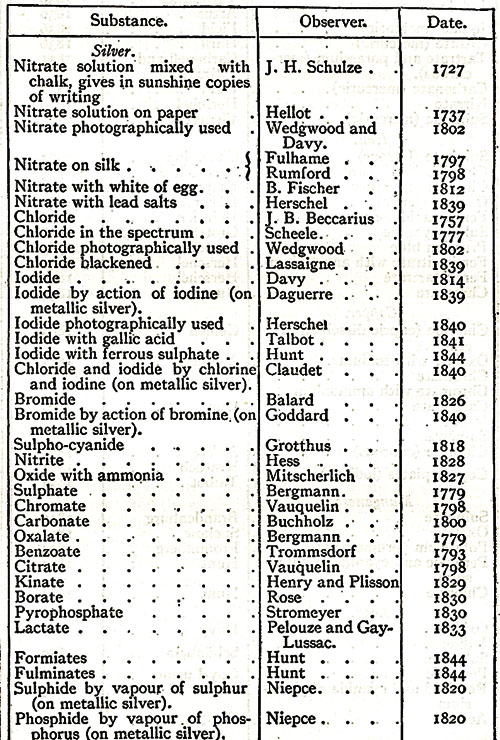

Table of experiments with light-sensitive coatings on paper from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, starting as early as 1727. Notice the presence of Wedgwood, Davy. Herschel, Talbot, and Niepce.